Russian photographer Nikita Teryoshin documents international exhibitions of weapons systems. He talks to iMEdD about the unknown world where billions of dollars and battlefield cynicism coexist.

Armaments: Israel and the others

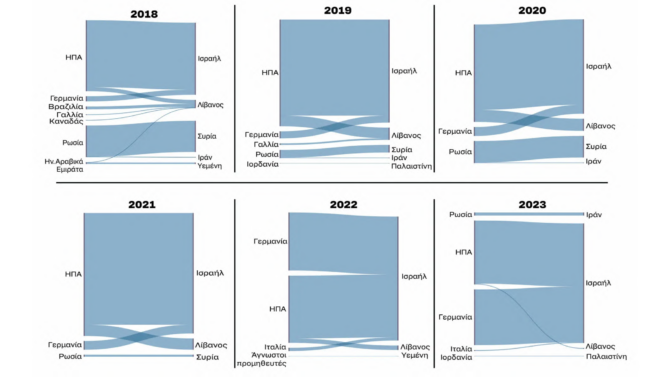

Data from the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI) on international arms transfers to Israel, Syria, Iran, Lebanon, Yemen and Palestine. What does the data on the quantity and origin of transfers show?

Canapés and cocktails are served next to a warship gun system. Visitors walk through the corridors holding the bombshells they have just purchased. Battle tanks are parked showily on thick carpets, and at the same time, fighter planes in formation put on an impressive show in the sky.

The international arms fairs are the opposite of the battlefield. Their labyrinthine corridors suggest a sterile, cold, and professional environment. They resemble technology or pharmaceutical trade shows. The sense of normality, however, is immediately contrasted with the advertised products: tanks, drones, radars, and multi-million-dollar bombs. Add to this the largely cynical slogans –“70 years defending peace”– of the Russian company that markets the Kalashnikov, as well as “Engineering for better tomorrow,” “Next Generation Lethality,” “First See, First Kill.”

Russian photographer Nikita Teryoshin has been visiting international arms fairs worldwide since 2016. His book, Nothing Personal: The Back Office of War, published by GOST, offers a unique perspective on the cynical and often corny way they are sold. “I think this entire project is also about the banality of this industry. They might as well be selling vacuum cleaners or cars,” he tells iMEdD from Berlin, where he has lived for the past few years.

An “explosive”… cake

The Russian photographer’s investigation began when he gained access to the International Defence Industry Exhibition (MSPO) as a VICE reporter. This is the largest arms fair in Eastern Europe, bringing together 22,000 participants in Kielce, a city of 170,000 inhabitants in southern Poland. Having visited the world’s leading arms fairs, he notes that in the Middle East, arms fairs are always notable for their spectacle.

Teryoshin recalls an exhibition in Abu Dhabi in 2019, where a sugar paste cake appeared on two wooden pallets. “It showed an explosion, a fighter plane flying, a tank, a warship, and a soldier with a rifle,” he says. As guests started eating it with disposable forks, it began to look more and more like a battlefield.

“I’m well aware that [at the same time] there was a war going on in Yemen, with the Emirati-Saudi alliance fighting the Houthis, bombing hospitals and schools.”

He describes the arms fairs in Russia as “a kind of Disneyland for war.” The exhibition center is located a few kilometers outside of Moscow, near Patriot Park, a large theme park dedicated to the Soviet victory in World War II. When he visited Patriot Park in 2019, he couldn’t help but notice the Central Cathedral of the Russian Armed Forces, which dominates in its khaki hues, as well as the golden domes and crosses that reach a height of 95 meters.

Following Russia’s recent invasion of Ukraine in 2022, the hosts chose to display German and American tanks brought from Ukraine. The same thing happened in 2019 when the exhibition center displayed parts of tanks and other equipment brought from Syria.

Rockets and coffee

For the cover of his book, Teryoshin chose a photograph that, he says, reflects the banality of the exhibitions. A misplaced cup of coffee next to four missiles worth 4 million dollars. “That says something more about the industry. The banality of the misplaced coffee cup, a white cup with imperfections, [where] missiles worth 1 million dollars each are displayed. The cup served a functional purpose, and you can find it all over the world,” he says.

There are no faces anywhere in the book, as he does not want to target the participants but rather show how the industry works. “But when you look at the whole picture and see all the photos together, you realize that they are part of a bigger story,” he says.

Guns and bananas

The preface to Teryoshin’s book is signed by Linda Åkerström, who works for the Swedish Peace and Arbitration Society, a non-governmental organization that aims to reduce or eliminate states’ armaments for war and to promote peace through actions and lobbying the Swedish government. According to the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI), Sweden was the 13th largest arms-producing country in the world in 2023 and appears to have one of the strictest systems for controlling arms sales to other countries.

In 2018, following revelations that the Swedish government was collaborating with regimes like Saudi Arabia, the Swedish parliament introduced the so-called “democratic criterion.” In effect, it is a set of criteria in the relevant legislation to ensure that Swedish arms are not sold to illiberal countries that do not respect human rights and democracy.

The language used in the legislative amendment is unclear, Åkerström tells iMEdD. “They used language saying that if there was a significant democratic deficit in the buyer’s country, the sale would be blocked. This was deliberate because they wanted to be able to exempt themselves from democratic restrictions for the needs of the arms trade. It is clear,” she notes.

Her team collected data on arms transfers from Swedish industries, showing that sales to illiberal and dictatorial regimes increased after the “democratic criterion” was added to the legislation. Arms sales agreements often avoid scrutiny under the guise of national security or private contracts. “I think security is something that states consider to be strictly their own business. They don’t want to cede power to anyone else in this regard, so I think it’s very difficult to regulate,” says Åkerström.

At the same time, while the arms trade is regulated by international agreements such as the UN Arms Trade Treaty (2013), several of the largest arms exporting countries, such as the United States and Russia, have not ratified it.

We read again from Åkerström’s preface to Teryoshin’s book: “The global arms trade is less regulated than the global banana trade,” she writes.

Read all articles and analyses of the Special Report: “Armories of the Middle East” here.

This article was first published on Feb. 22 in the weekend edition of the newspaper “TA NEA”.

Translation: Evita Lykou