Across the sessions we followed at the 14th Global Investigative Journalism Conference (GIJC25) in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, six moments stood out for reshaping how we think about journalism today. They ranged from calls for wide collaboration and sharper scrutiny of AI systems to survival strategies under authoritarian pressure and insights on investigating grand, cross-border corruption and reporting on genocides.

Maria Ressa: “This is a time for radical collaboration and creation”

Maria Ressa — a 2021 Nobel Peace Prize laureate, co-founder and CEO of the pioneering investigative outlet Rappler — opened GIJC25 with a warning: amid rising authoritarianism, tech oligarchs, funding cuts, and attacks on journalists, “if we do not collaborate radically and create, medium sized organizations will be collapsed”; many of them could disappear within a year. Her urgent message was clear: the current crisis must be turned into an opportunity for impact and survival. She drew on her own experience in the Philippines to demonstrate that holding power to account can lead to both justice and financial sustainability, noting that the year she faced eleven arrest warrants was also when Rappler became profitable, as audiences rallied around their courageous reporting.

Ressa warned algorithm-driven disinformation, hatred, and the “normalization of lies” threaten facts, democracy, and marginalized communities, while pointing out that 2026 is a crucial window for independent newsrooms to secure rights, partnerships, and new business models — and to reassess dependence on social media.

She concluded by urging journalists to enforce existing human rights and press freedom standards, especially in the EU, to avoid further marginalizing already vulnerable groups, and to build alternative, public-interest tech and real-world spaces where people can speak freely without algorithmic manipulation. “Everything we knew as an industry has been destroyed,” she said, highlighting that “online violence is real life violence”. Framing information integrity as “the mother of all battles”, she added, “without facts, you cannot have truth. Without truth, you cannot trust. Without any of those three, we cannot have a shared reality. Without any of these, we cannot have democracy”.

>> Read more on this session by GIJN here.

Christo Buschek: “AI just sits at the long tail of the datafied society of the last 20+ years”

In a talk that cut through the noise surrounding artificial intelligence, Christo Buschek — a Pulitzer Prize-winning independent software developer and investigative journalist at Der Spiegel — urged journalists to confront a central truth: technology is not neutral. Challenging this persistent misconception, he stressed that “Technology is the result of choices and values […] Technology does not just exist. It is always constructed. It is built. Technology is neither exceptional nor inevitable. In short: people make technology.”

He began his session on “Investigating Datasets to Hold AI Accountable” by reframing the idea of algorithmic accountability. The term, he noted, fractures depending on who uses it. In academia or in government and corporate auditing, it often means auditing algorithms to see whether they function as claimed. In journalism and civil society, Buschek said, accountability demands something equally valid: revealing how algorithms affect real communities and whose interests they ultimately serve. “These two approaches have to mutually inform each other”, he argued.

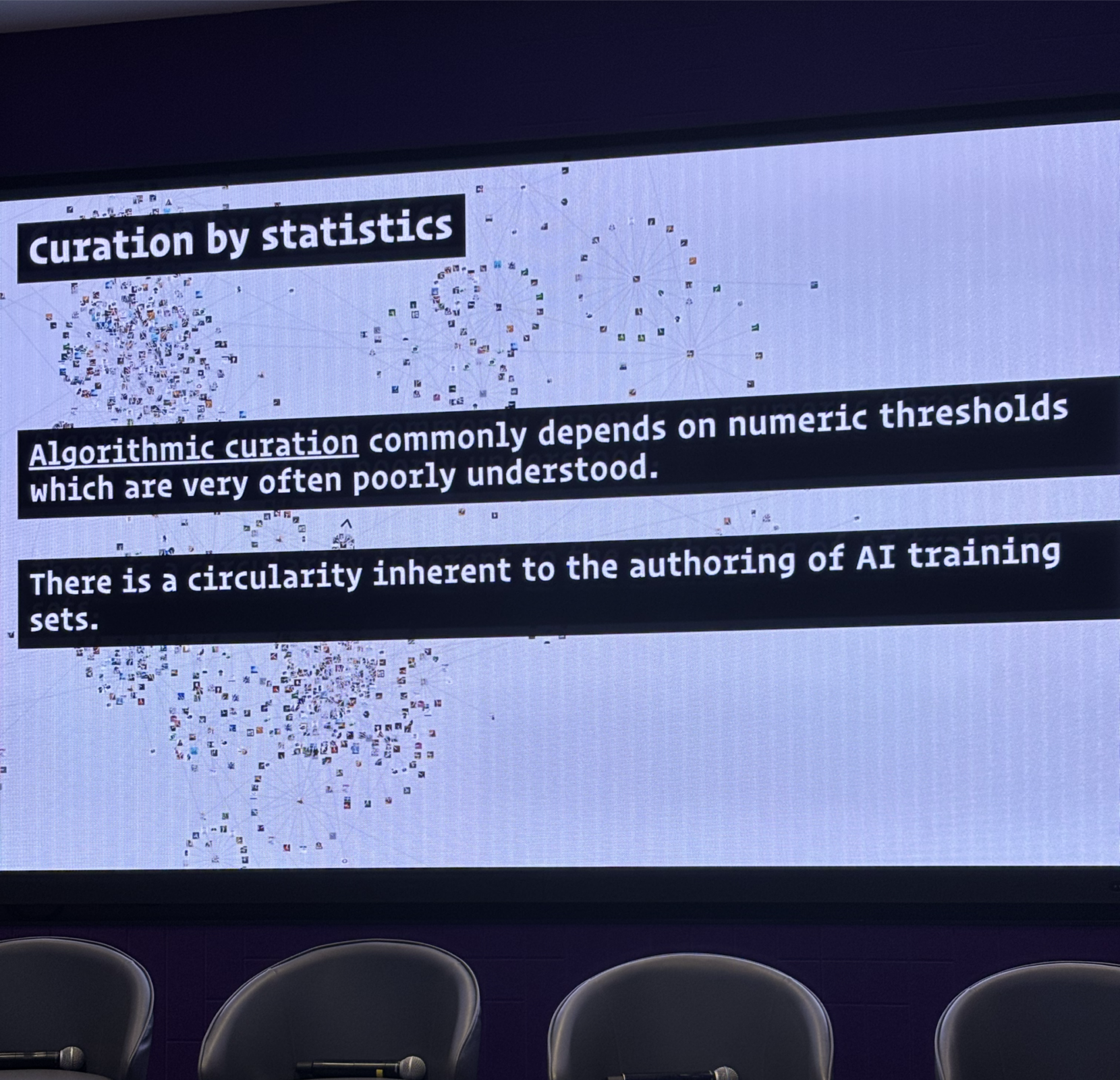

Buschek warned that today’s “AI just sits at the long tail of the datafied society” of the last more than twenty years. Far from acting autonomously or intelligently, AI is a socio-political project built on human choices, commercial incentives, and hidden biases. To show how profoundly human decisions shape supposedly impartial systems, Buschek dissected LAION-5B, one of the massive image datasets used to train contemporary AI models. Derived from the source corpus of The Common Crawl, LAION extracted over 50 billion images; then, LAION selected 5.8 billion — through statistical thresholds determined by other models. This, Buschek noted, exposes a troubling circularity: AI systems are now trained on datasets built by other AI systems, each embedding its own blind spots. The result is not a reflection of how humans see the world, but of how search engines and structural biases embedded curation by statistics interpret it.

For journalists, this is exactly where scrutiny must fall. “Dataset investigation”, he said, “is a method for holistically interrogating AI systems – the data, the models, and the effects”. Examining how training data is assembled, filtered, and shaped is one of the few tools available to expose emerging effects of new algorithmic systems that “are non-explainable and nondeterministic.”

Gustavo Gorriti: Being “tactically cautious” is key to staying safe

The Peruvian investigative journalist Gustavo Gorriti still abides by a kind of courage based on cold risk analysis and survival. In the early 90s, he was abducted in Lima over his reporting on the Fujimori regime’s corruption, but an emergency plan he had set up – his wife alerting editors and human rights groups – triggered international pressure that forced his release two days later. Today, as head of IDL-Reporteros, he’s still exposing corruption in Peru, now under siege from smear campaigns, politicized probes, harassment, and even a public death threat from Lima’s mayor.

Speaking during the session “Investigating in the Face of Repression”, Gorriti referred to a survival toolkit for reporters confronting power: Being “tactically cautious,” he said, means steering clear of obvious traps, protecting sources when targets may hit back, never asking anyone to take a risk you wouldn’t take yourself, and loudly defending your work and name under attack. Gorriti, who recently overcame stage IV cancer, also reminded colleagues that self-care is of great importance: “You want to avoid burnout after working through two sleepless nights? Sure, you can go to the nearest bar, but you can also decide to go to bed, sleep, and exercise the next day.”

One of his great achievements came from his outlet’s role in uncovering the Odebrecht scandal, a huge bribery and campaign‑financing scheme that stretched across eleven Latin American countries and contributed to the indictment of four Peruvian ex‑presidents, one of whom, Alan García, killed himself when police arrived to arrest him. That disclosure earned IDL‑Reporteros 2019 GIJN’s Global Shining Light Award but also unleashed a wave of reprisals: orchestrated disinformation about his cancer diagnosis, mobs gathering outside his home, and smear campaigns designed to destroy his credibility. These methods reflect, he underlined, a universal pattern, where “attacks on journalists’ revelations and reputations” are used to neutralize investigative reporting. Finally, he urged younger journalists to deepen their storytelling skills by reading great works of literature, not just perfecting data mining and digital research skills. His advice was simple: “Read!”.

>> Read more on this session by GIJN here.

Charles A. Adeogun-Phillips: The only thing that it’s worse than committing genocide is denying it

International prosecutor Dr. Charles A. Adeogun-Phillips offered journalists a rare, unvarnished look at the fault lines of global justice — and why reporters must interrogate them — in a session moderated by Lina Attalah, publisher and founding editor of Egypt’s award-winning MadaMasr newsroom, and Emilia Díaz-Struck, GIJN executive director. Using Nigeria’s decades-long struggle to recover billions siphoned to the West, he exposed how asset restitution is often framed as generosity by wealthy nations while masking deep inequities: only portions of the stolen funds are returned, and usually under restrictive conditions. For reporters covering grand corruption, he stressed that secrecy jurisdictions, competing legal claims, and deliberate procedural delays are themselves part of the story.

As vice-chair of the Board of Integrity Initiatives International (III) — a Boston-based NGO advocating for the establishment of the proposed International Anti-Corruption Court (IACC) —, Adeogun-Phillips argued that a dedicated institution is needed to tackle grand corruption when kleptocrats still control their countries’ justice systems.

A former lead genocide prosecutor and head of special investigations at the United Nations, his message to journalists reporting on genocides was clear: follow incentives, not just the numbers. For international criminal law to thrive, he reminded the audience, cooperation between states is essential. Sharing lessons from Rwanda — where the only live footage came from British Nicolas Quentin Hughes—, he urged journalists to recognize cultural context, gender dynamics, and the limits of foreign investigation. “The only thing that it’s worse than committing genocide”, he emphasized, is denying it.

>> Read more on this session by GIJN here.

Karen Hao: “In Silicon Valley, they have an imperial ideology and agenda”

Award-winning journalist and author Karen Hao delivered a sharp critique of the power structures, ideologies, environmental impacts, and ethical blind spots within the global artificial intelligence industry, particularly among Silicon Valley giants. She mentioned that the problem lies beyond capitalism in a libertarian ideology that values freedom to develop technology over social responsibility. Such thinking encourages a lack of strong controls, with OpenAI, for example, having “the fewest accountability mechanisms” in an industry where an “imperial ideology and agenda” prevail.

In a discussion moderated by Gina Chua, executive director of the Tow-Knight Center, Craig Newmark Graduate School of Journalism at CUNY, Karen Hao helped attendees better understand the impact of AI and the tech industry driving its development.

Hao challenged the idea of inevitability in AI development, arguing that it does not necessarily have to replace human expertise. She asked, “Why build technology to replace humans when we already have humans?” She also issued a word of warning about AI training data, stating that “the internet has dark corners” where bias and misinformation thrive. Despite the grave concerns she raised, Hao closed with a hopeful, empowering message: “Recognize that this industry is not inevitable.” She meant to say that the trajectory of AI development is not inevitable or fixed.

She concluded by emphasizing that “journalists have a role in how it can go.” The optimism was fueled by the belief that critical scrutiny and public pressure could change the course of this growing industry, as “we are at a point where we can turn the ship around.” This direct address to the mandate for investigative journalists challenges the AI establishment in shaping a more equitable technological future.

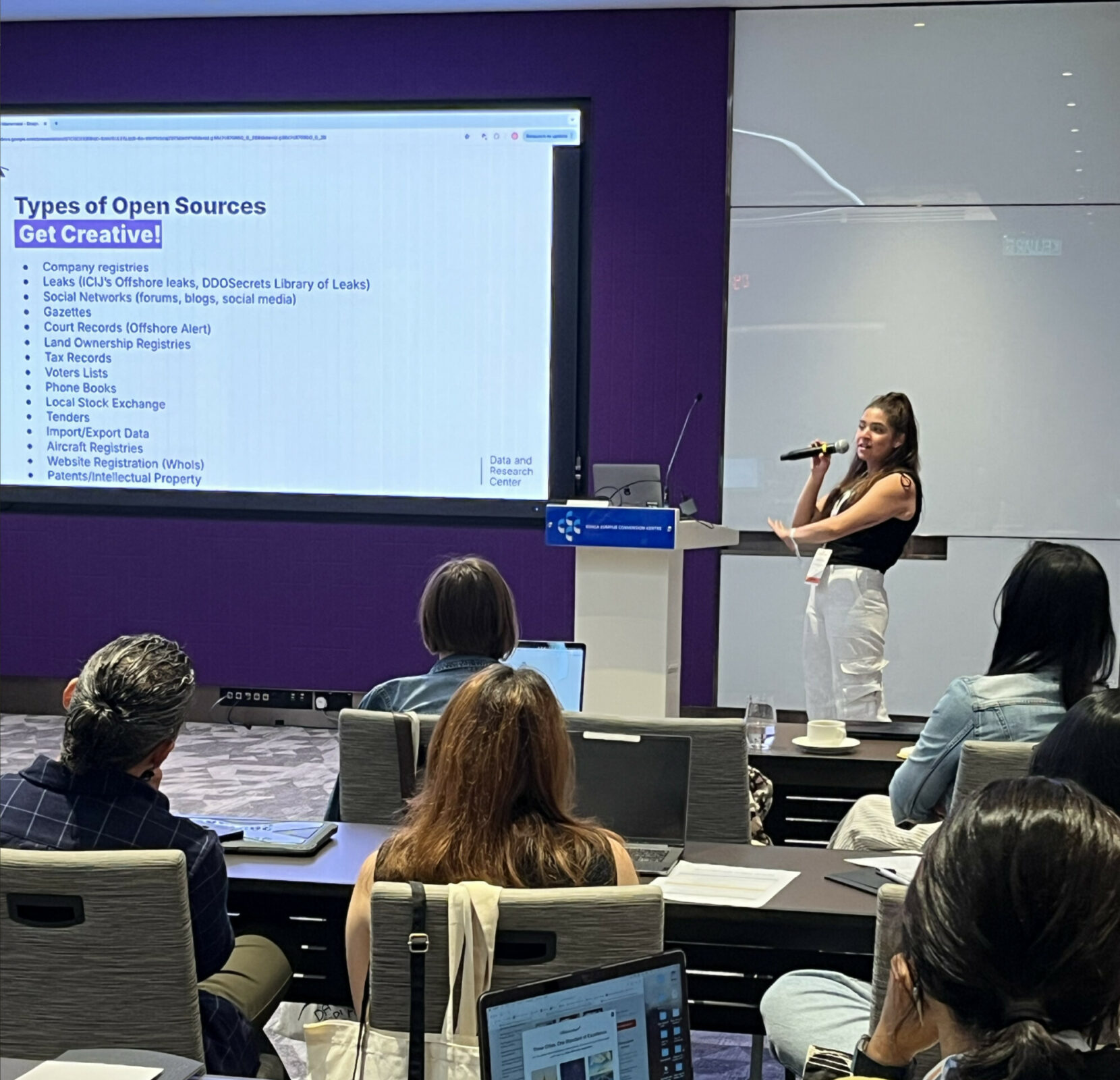

Karina Shedrofsky: “You’re only as secretive as your most exposed associate”

“You’re only as secretive as your most exposed associate. If you can’t find any information on your person of interest, look for their associates and family members, and try to find things associated with them”, explained Karina Shedrofsky, Co-Founder and Director of Research at DARC, as she summarized key tips and tricks for follow-the-money investigations after her masterclass. When a primary subject seems invisible, a smart move is to follow the people orbiting them. Their digital habits, public filings, and paper trails often reveal what the principal has carefully concealed.

Shedrofsky insisted that real power in asset hunting lies in public records worldwide, which form an uneven yet rich investigative terrain. Company registries, land deeds, incorporation dates, shareholder structures — each offers a fragment of a larger picture and understanding how these fragments differ across countries is essential. She framed asset tracing as a creative discipline, “more of an art than a science.” Public records, open-source sleuthing, paid databases, and company registries are all part of the journalist’s toolkit.

Martha Mendoza, a two-time Pulitzer Prize winner and current correspondent at Frontline, reinforced this broad, multidisciplinary approach: She demonstrated techniques and tools for open-source investigations, focusing on tracking ships and planes. But OSINT, she reminded us, is not limited to online clues. Freedom of information requests and public records remain foundational – and “real people are also open-source”, a crucial counterbalance in an era dominated by data.

Shedrofsky and Mendoza delivered this two-part training on follow-the-money and open-source investigations exclusively to a cohort of 20 international journalists selected as iMEdD and GIJC fellows. Their full-day session took place on the pre-conference day dedicated to high-impact workshops and gatherings.

Εικονογράφηση: Ευγένιος Καλοφωλιάς