One of the most consequential conflict photojournalists of our era, Ron Haviv, talked with us about how his photographs have contributed to the downfall of dictators, assisted war crimes tribunals, and led the way for the representation of conflict for the world —from Panama and the former Yugoslavia to Darfur and Ukraine. We discussed the power and limitations of visual representation in journalism, particularly in the reporting of history.

Portraits of Ron Haviv: Petros Toufexis/ iMEdD

Photographs: Courtesy of Ron Haviv/ VII Foundation

Ron Haviv is one of the most consequential conflict photojournalists of our era. He has spent over three decades on the frontlines of history, photographing more than 25 conflicts in over 100 countries. His work has not only documented history but actively influenced it —from serving as evidence in war crimes tribunals to helping trigger shifts in US foreign policy. We first sat down with him at the iMEdD International Journalism Forum to explore the full range of his career, focusing on the enduring ethical mission of photojournalism and the forces currently reshaping it: from the critical educational role of the VII Academy to the way we perceive and verify visual truth. We later met at this year’s Global Investigative Journalism Conference (GIJC25), where we expanded our initial conversation to reflect how these questions continue to evolve. As he put it during his GIJC25 “Investigative Visual Journalism” workshop, “Visual journalism is a field of practice that incorporates reporting, visual documentation, narrative storytelling, and public accountability,” a definition that underscores both the gravity of the work and the moral imperative that accompanies it.

Over several decades, Haviv’s images have spanned the full spectrum of photojournalism’s impact—from the war crimes courts in The Hague, where his photographs were part of the evidence, to his coverage in Panama that may have influenced US policy, and his ongoing documentation of humanitarian crises in places such as Darfur and the Democratic Republic of Congo. Taken together, these different outcomes naturally lead to a central question:

How have these different outcomes ultimately defined your view of photojournalism’s core purpose and its enduring ethical responsibility in the contemporary media landscape?

Now having the ability to look back at my work and its impact —and also its lack of impact— over the course of the last 40 years or so, I can see that not only my work but the work of visual journalism plays a role in society, that it partners with society in its ability to inform, to educate, to cajole, to embarrass people into action.

I think that the overall goal has always been, relatively from the beginning of my career, to create work that has the ability to have an impact, to push, to motivate people into some action, or at the very least to have understanding and awareness of what’s going on, especially in terms of places where their governments are often complicit, responsible, or have a play in what’s going on in a faraway place.

As an American, often that’s almost the entire world, so I feel that responsibility as an American visual journalist.

The overall goal has always been to create work that has the ability to have an impact or at very least to have understanding and awareness of what’s going on, especially in terms of places where their governments have a play in what’s going on in a faraway place. I feel that responsibility as an American visual journalist.

Ron Haviv

What was the most defining moment in your career that made you realize the power of photography, the power of the image?

I think it’s probably just a combination of two things. The first would be right at the beginning of my career, my first real foreign assignment in the Central American country of Panama, where a dictator held elections, lost the elections, nullified the elections, and then had the would-be victors beaten.

I photographed the vice president-elect [editor’s note: Guiellermo Ford], covered in the blood of his bodyguard, who was killed trying to protect him, being beaten up by a paramilitary supporter of the dictator. That photograph was featured on the front pages of newspapers and magazines around the world. Later that year, when the United States invaded Panama to overthrow the dictator, the president of the United States [editor’s note: George H. W. Bush] referenced the photograph as one of the justifications for the invasion.

It wasn’t whether I agreed with the invasion, and I certainly didn’t believe the invasion was solely due to the photograph, but the photograph did play a role in the discussion that led to the invasion. It was discussed in Congress, used by the opposition on the ground in Panama, and utilized to raise awareness and garner more support for overthrowing the dictator.

Then, three years later, in the third war in former Yugoslavia, I was in Bosnia, and I was able to document a Serbian paramilitary group known as the Tigers, executing unarmed Muslim civilians. I managed to take a photograph, basically documenting what later became known as ethnic cleansing. The photograph was also published around the world, but this time there was no reaction. The same president who reacted to the photograph in Panama was in power during the war in Bosnia and did nothing. And so, while I was, I don’t think naive, to believe that the Panama picture succeeded on its own, including the foreign policy of the American government, when a similar photograph came into play a few years later, it was not part of the American foreign policy, and therefore, nobody was going to react to it, and nobody did. It was only after time that the photograph began to take on its own power.

It was in those two instances that I realized both the power and the limitations of what a photograph could do.

You’ve often said your work “documents history.” Thinking about all the historical moments you’ve covered, which one feels most crucial for your archives, and how does your role as a witness influence your continued drive to document history?

First of all, the work that I do is not completely altruistic, right? It is because I have this interest in history. For me, starting early on, to be in Berlin when the wall came down, to watch Nelson Mandela walk out of prison, to be at Baghdad when the statue came down, to witness these things for myself, real history, it’s remarkable, it is incredible, what an amazing way I think to live my life.

Now, when you add the fact that I’m able to take photographs and share my subjective interpretation of these events with people, showing them what I saw and what I think, it is an incredible privilege. That itself is a motivating factor in continuing to do this, because the world continues to change.

In the time since I started, the world changed in 1989 when the Berlin Wall came down, in 2001 with the Twin Towers, then the War on Terror, then the Arab Spring, all these different things that need documentation and have had an incredible impact on the lives of people in the world.

For me, to be able to see it, document it, and experience it is quite incredible.

Photography allows for multiple interpretations, and framing is critical. Have you ever had your photos misinterpreted or presented in a way that distorted their meaning?

The biggest one and probably the most impactful one was from a photograph in Bosnia. I took a photograph of ethnic cleansing, and it was a very well-known photograph, and it’s been continuously published around the world. But what’s important about the photograph, aside from what you see in the image, is the caption, so you know what’s going on, who’s who, what does the symbol on the soldier’s arm say, who are the civilians that are dying, and so on.

During the first part of the war in Ukraine in 2014, a well-known Russian blogger with millions of followers took the photograph and let the image stand on its own. All he did was change the captions and say, “Ukrainian soldiers kill Russian civilians”. And then the photograph goes viral in Russia. Τhen somebody made an exhibition and used the same caption. So, I think to this day, if you show that photograph to people in Russia, they won’t identify the victims as Muslims and the assailants as Serbs.

The work that I do is not completely altruistic, right? It is because I have this interest in history […] In the time since I started, the world changed in 1989 when the Berlin Wall came down, in 2001 with the Twin Towers, then the War on Terror, then the Arab Spring. For me, to be able to see [the impact on lives of people], document it, and experience it is quite incredible.

Ron Haviv

Photojournalists who cover conflicts and civil unrest have long been challenged to decide whether to put the camera down and offer help when faced with a victim. How do you grapple with that ethical dilemma, and how difficult is it to make such a profound decision under pressure?

It’s a personal decision. Everybody has to make their own choice. So, I don’t think there’s a right or wrong answer, but I had to decide early on in my career what I would do when it would happen. On paper, it’s simple.

If I’m the only one there that can help and I’m not going to get killed, I’ll help. If somebody else is there, if there’s a doctor, a medic, somebody else who can do the same thing I could do, then I’m going to do my job, because I am there as your eyes. I have a responsibility; I’m not there as an aid worker. There is no question I’ve had the ability and opportunity to save people, and I’ve had times when I felt there was nothing I could do or I would be killed, and I was left with the only thing I could do, which was to try to document the aftermath. There have been times when I wasn’t allowed to do even that because I had a gun put to my head.

There have been times when my colleagues and I have taken wounded people to hospitals and feeding centers. The only thing I don’t do is insert myself into the situation once I’ve interacted. Then, I’m no longer a journalist, and I stop taking photographs. I don’t photograph things that I influence.

Following Jean Baudrillard’s reasoning that “a war that is not broadcasted is a non-existent war”: Do you find that some conflicts become more real or “existent” than others simply because they receive more media coverage?

Absolutely. There was a Reuters correspondent who was killed in Sierra Leone named Kurt Schork. He was one of those journalists who would look for these non-existent wars and realize, “Oh, nobody’s paying attention to this.” And when he would show up, everybody else would follow, because this was something we needed to pay attention to.

There’s a lot going on in the world, and the audience is often completely burned out, but that doesn’t mean that it shouldn’t be documented or that we shouldn’t pay attention to it.

If I’m the only one there that can help and I’m not going to get killed, I’ll help. If somebody else is there, who can do the same thing I could do, then I’m going to do my job, because I am there as your eyes.

Rov Haviv

Since we are talking about documenting history and you have covered so many war zones, how do you feel about the fact that history in Gaza was not fully documented?

I don’t know if I like the phrase of that, because it would be unfair to the Palestinian journalists who risked their lives and did an incredible job of documenting it.

At the same time, while we saw the impact of Israel’s attacks on Gaza civilians, which was one part of it —and a very, very big part of it—, we only saw a very small glimpse of Israeli soldiers, almost nothing of them in action, and we didn’t see Hamas at all; it’s like Hamas was a ghost. So, you can say two-thirds of that conflict was not documented. If you want to use the word “fully” in that way, then I think yes, it’s very difficult to say it was fully documented.

But we have the same thing to some degree in Ukraine, right? The Russian side is probably a little bit more documented than Hamas, but still very limited. It’s very hard as a foreign journalist to get to the Russians to document what they’re doing.

In most wars, all sides are becoming very aware of the value or importance of outside imagery. All sides document themselves with citizen, government and military “journalism”. In cases like Ukraine, Russia, Gaza, there is always a need for independent journalism to be done on the ground. It would fill the story out in a different way. But again, that being said, in the war in Gaza the amount of powerful and, as far as I’m concerned, believable material that has come from the Palestinian journalists can’t be denied, and it’s what we have.

You co-founded the VII Photo Agency. What was the vision behind starting an agency? And how has it adapted to the continuously evolving landscape of photojournalism and visual journalism?

In about 1999 through 2000, 2001, Mark Getty from the Getty family and Bill Gates from Microsoft made an assumption that whoever controls imagery in this new digital world would be in very good shape in terms of finances. So, they both started photo agencies, one called Getty Images, the other called Corbis. Then they proceeded to acquire all of these smaller photo agencies, effectively cornering the market and controlling the imagery used on the internet.

Three colleagues —Gary Knight, John Stanmeyer, and Antonín Kratochvíl— and I were represented by a small agency called Saba, run by a guy named Marcel Saba. And then Chris Morris was with Blackstar, James Nachtwey was with Magnum, and Alexandra Boulat was with SIPA. All of us felt that the agencies were going to be bought up by these conglomerates, except for Magnum, and we were not going to have much of a say in how our work was represented, we would be part of a multinational corporation, and we basically wouldn’t have any control over the business side of our photography and the distribution of our photography.

So, Gary Knight and John Stanmeyer thought it was a good time to break away from these corporate entities and start something where we could control our own destiny. It was primarily a decision driven by business, but one that also emphasized independence in terms of our work, including where our work could be seen, who we work for, and having control over our own destiny.

As the United States moves into a second Trump administration, the idea of “fake news” remains deeply rooted, from the highest political offices down to everyday conversations on the street. At the same time, economic pressures on traditional media have reduced the number of employed visual journalist.

Ron Haviv

Given the current economic pressures, rapid technological change, and deep political polarization in the United States, how do you think these forces will shape the future of journalism and photojournalism, both in terms of working conditions and the kind of stories that will be told?

As the United States moves into a second Trump administration, the idea of “fake news” remains deeply rooted, from the highest political offices down to everyday conversations on the street. At the same time, economic pressures on traditional media have reduced the number of employed visual journalists—pushing audiences and newsrooms to rely more heavily on “new” and alternative media for everything from politics to war coverage. Yet there is often a growing disconnect between the role of a trained visual journalist and the amplification of certain narratives circulating through these newer platforms.

This raises ongoing and essential questions: Who is a journalist? Who is their audience? And how is reporting being produced, verified, and distributed? In visual journalism especially, the departure of experienced practitioners has created space for the rise of the citizen journalist—often providing immediate and invaluable perspectives, but also further blurring the boundaries of expertise, credibility, and responsibility.

What is your general view on the future of journalism and photojournalism? What gives you hope, and what keeps you up at night most of the time?

What continues to give me hope is that you still see instances where imagery can rise above the noise, still have an impact, and still have people remember photographs. Let’s just start with the photograph of Aylan Kurdi, “the child on the beach”. Several photographers took that photograph, which went around the world. Most importantly, the then-Chancellor of Germany, Angela Merkel, spoke about that photograph and talked about how it changed her opinion about migration. So, it had a dramatic impact alongside the other millions of people who saw that photograph.

We had a Getty photograph from the US border with a child crying. Being separated from his mother, she was being questioned by border police, which went viral and became a talking point for the conversation about the border. There are times when photographs can rise above the discussion and engage people. This gives me hope that it can continue to happen.

On the other hand, we have so many images taken that what if these images are no longer able to rise above the noise, and people become overwhelmed by photojournalism, or simply don’t care or don’t want to pay attention to it. That’s fearful. When that happens, especially when photographers are risking their lives to tell these stories, it’s a waste of that energy and effort; most importantly, it is completely disrespectful to the stories we’re trying to tell.

My fear is that it will reach a point where people are only looking inward and won’t care, even if they are somehow responsible for other people’s lives. They just don’t want to acknowledge it, adjust to it, change it, or make it better. That’s one of the reasons why this work exists: to remind them we’re all interconnected.

The diversity of voices is one of the biggest changes, certainly from when I started.

Ron Haviv

In an era where anyone can capture and share moments on social media, how has this reshaped the role of the photojournalist?

I don’t think it’s changing anything. You’re talking about places and people photographing things that I was never going to see, or any of us ever going to ever see before. So, this is great. This is an extra layer of visual information. But these are often just snapshots. These are like moments in time, which can be very dramatic, incredible, and powerful; no question about it. But in terms of this idea about authorship, integrity, telling a story, narrative, the citizen journalist is not doing that; that’s still our job. It’s still what we’re trained for. So, they’re different things.

But again, this idea of citizen journalists, people wanting to take photographs with their phones, or small cameras, and becoming more interested in photography, is great for the idea of photography, because people are starting to appreciate it even more, and then they become engaged not only as content providers, but also as content consumers.

Through VII Academy and Foundation, you teach the next generation of photographers. Do you observe significant differences in how younger photographers approach and value their work compared to previous generations?

Well, I think now because of technology and the affordability of cameras, whether motion or still, they have the ability to tell their own stories of their own communities and so on, in a way that they never had before. Through many of our students, we’re seeing stories from Libya and Iraq and Afghanistan and Peru and Colombia.

I think the diversity of voices is one of the biggest changes, certainly from when I started. [Back then] it was still mostly male-dominated —mostly western male and certainly mostly white. I think that there’s room for multiple voices; I think now we’ve reached that point. Something that the Foundation through the Academy is very conscious of ensuring is that they are able to learn and to tell their stories with authorship, with integrity and with the principles of proper photojournalism.

If you had to choose two photos that characterize you, which ones would they be and why?

As a photojournalist, I would have to go back to the two early photographs, one from Panama, and one from Bosnia, because they basically created these two pillars. One of the possibility of affecting change and the other the limitations of what you can do. So, it would be the vice president being beaten and the civilians being killed.

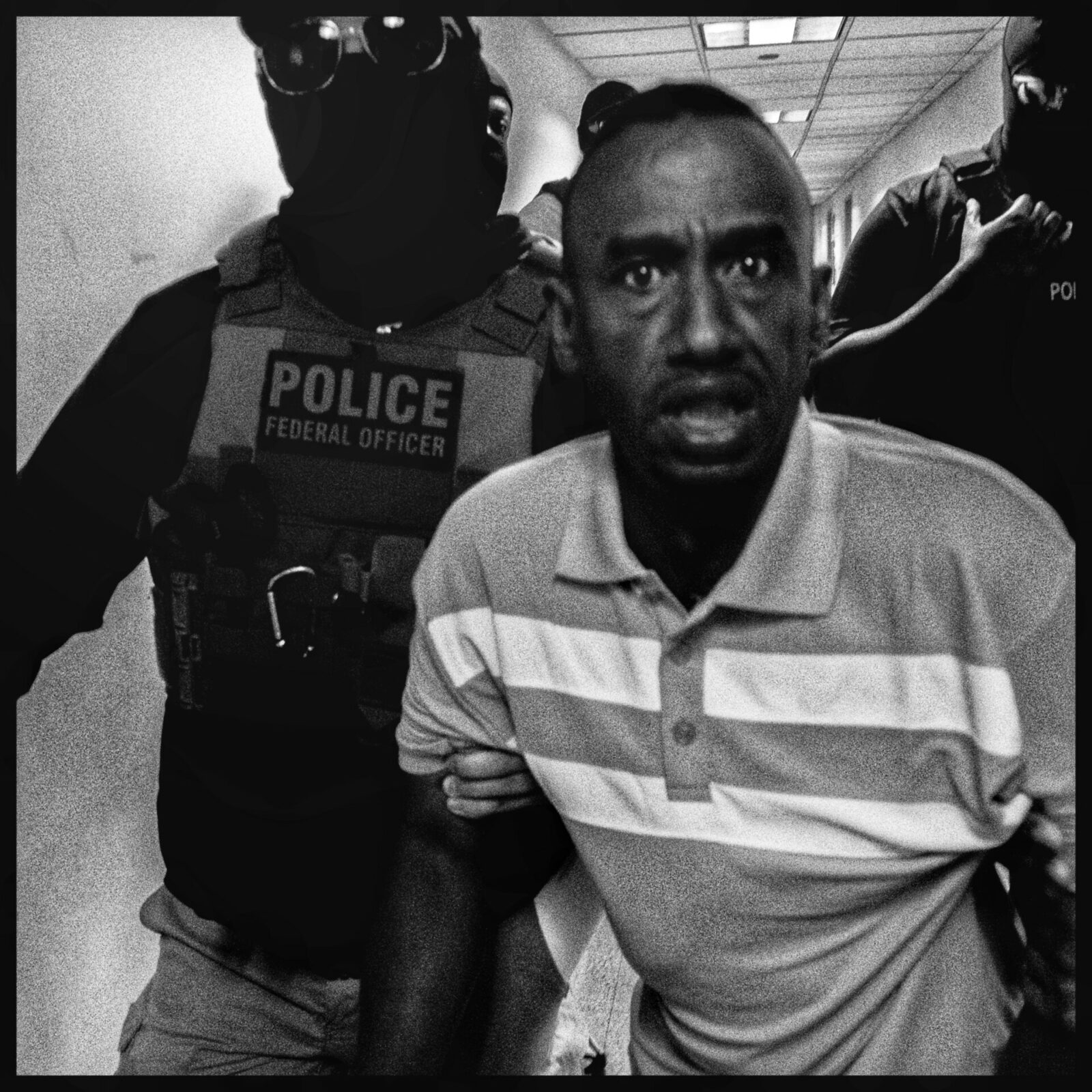

As a person, maybe there would be a picture from Bosnia of this Albanian guy from North Macedonia, a guy named Hajrush Ziberi, who’s been taken prisoner, and his hands are like this, and he’s asking me basically to help him. He knows he’s going to be killed. And I couldn’t help him. That picture has a lot of impact on me, because I also met the family, spent time with them, and am still in touch with them. I had thought that when I was going to meet them, they would blame me for not saving their son, and they were exactly the opposite and thanked me, which I thought was so kind; it’s hard to believe. His death didn’t go unnoticed, and it had an impact.

There’s a photograph from Darfur, of a young girl with her two friends. She’s about to walk seven to eight hours in the desert to get firewood for her family. Her life was very difficult. I tried to find her after the picture was taken, but I was never able to find her. I don’t know if she survived or not. But the way she holds her body, the clothing and color of the clothing that she’s wearing, it’s a very resilient yet resigned image. She was trying to be helped by the international community, and to this day, 20 years later, Darfur still is not helped, so it’s very symbolic of kind of my approach or my feeling that in the end, I think there was some good done with some of my work, but most of the time the work failed.

What is the most important lesson you’ve learned during your long and distinguished career?

That I can’t be everywhere at once. The world continues to change, so there’s always another story to come. I strive to do the best that I can, always with utmost respect and dignity for the subjects I am photographing.

Ron Haviv, Co-Founder and Director of the VII Foundation, was a speaker at 2025 iMEdD International Journalism Forum, where he led a workshop titled “If I can’t see it, I can’t document it” together with photojournalist Nicole Tung.

This interview is published by iMEdD and is made available under a Creative Commons licence (CC BY-NC 4.0). This licence does not apply to the images by Ron Haviv included in this publication, which are published courtesy of Ron Haviv and the VII Foundation for the purposes of this piece. Any other use of these images by third parties requires their prior permission.