Elvira Krithari, Greek state broadcaster (ERT) correspondent in Syria, speaks to iMEdD.

Elvira Krithari was the first Greek journalist to enter Syria just a few hours after the fall of Bashar al-Assad. “It was one of the most challenging missions in terms of working conditions,” she told iMEdD in a recorded message on WhatsApp. “There are difficulties in communications, accommodation, and translation, but we rely on the generosity of locals.” She added, “The media ensures a certain level of objectivity—after all, we’re not historians or analysts, and we don’t have all the answers. But the initial reports through the lens of a foreign journalist often set the stage for those who will tell the story again.”

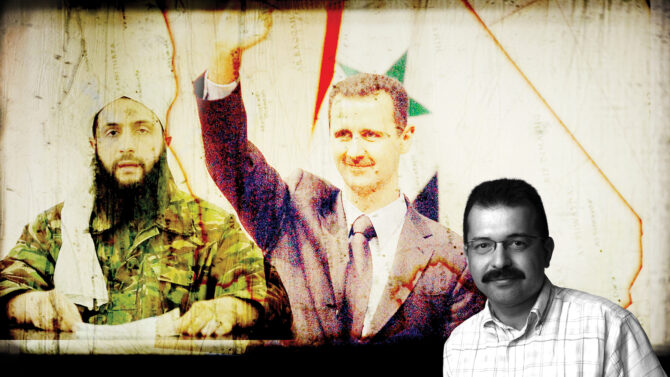

“In the history of Syria, there are no good or bad guys,” says Professor Sotiris Roussos

Sotiris Roussos, a professor at the University of Peloponnese specialising in the Middle East, helps us unravel the complex situation in Syria.

How did you get to Damascus on the first day?

At this moment (Wednesday, December 11, noon), we have just crossed the Al-Masnaa checkpoint and are driving from Lebanon into Syria. Damascus is about 40 minutes away from here. On our first visit, we stayed until 4 PM due to a curfew. Now, we’re crossing for the third time and planning to stay longer. We are in a car with a Syrian driver, and we have an internet connection because he’s set up a hotspot from his mobile phone. (Note: several times our communication was disrupted, and at times the messages we exchanged were interfered with by roadblocks along the route). We also have three cans of gasoline with us, which the taxi driver in Damascus requested. There’s a severe fuel shortage.

To make a quick border crossing, you need a smart driver. At the Syrian border post, we’re greeted by the opposition fighters who overthrew Assad. There’s no real control there—they want the foreign media to show the world what’s happened. They’re making victory signs and exchanging pleasantries with the driver. We are now driving towards Damascus, and on the opposite side of the road towards the Lebanon border, there are long queues of cars. These likely include people who are close to the regime, either searching for food or feeling uncertain about the new situation in Syria. Along the route to Damascus, there are damaged tanks in many places. And when you get to the city, it feels like there’s a constant celebration atmosphere.

Under what conditions do you work?

These are the most challenging conditions I’ve encountered in covering international crises. There’s a shortage of basic amenities, no fuel, and you can’t buy a SIM card because you need a Syrian passport. So, you ask a local to buy it for you or rent one to broadcast live—it’s crucial to have multiple SIM cards, which adds to the difficulty. You can’t book a hotel online either—based on my previous experience in Ukraine, I always carry a sleeping bag with me. It’s uncharted territory, so we rely heavily on the generosity of strangers, which is indeed ample, I must say.

How do locals—authorities and ordinary citizens—treat you as a foreign, Western journalist?

They are very friendly and eager to talk because they want to show what’s happening in the country. I’ve found great testimonials, but it’s hard to find a reliable friend and translator. I don’t feel insecure; the armed forces who took power seem keen to help and maintain a positive image. I don’t feel threatened as a woman; for example, I haven’t been asked to wear a headscarf. The women here are strong and assertive in the face of unfolding events.

What is the mood among the rest of the media?

Foreign journalists are well-connected with each other. There’s a group from the previous mission in Lebanon where we share practical information. The first instruction we received was to carry a GPS tracker, as kidnapping journalists in Syria was common, especially under the previous regime. In the chat group, colleagues share details about available car seats, ask if they can fly drones, and so on. The media operates with a sense of collaboration; it feels safe knowing I have access to a group where someone will respond immediately and look out for one another.

“Do whatever you need to do to survive in Syria”: the person behind Assad’s overthrow

Where did Hayat Tahrir al-Sham and its leader, who is playing a leading role in toppling the Assad regime, come from? The first years in Iraq, the “divorce” from al-Qa’ida and the next day. Dr. Hans-Jakob Schindler, Senior Director of the Counter Extremism Project and former Coordinator of the UN Security Council, talks to iMEdD.

Why do you think the presence of foreign media in Damascus is important?

It’s unprecedented what’s happening here—there have been overthrows of authoritarian regimes in the Middle East before, but this one is striking in how quickly it all transpired and how the international community was caught off guard by the advance of HTS. It’s also unusual, at least temporarily, with al-Dschaulani building bridges to the West—he’s spoken to CNN, made proclamations of unity, and there’s a significance to all this.

I want to tell you that I’m deeply moved. I did a very touching interview with a young boy who spoke little English but was very deliberate with his words. I asked him, “What do you think now with the jihadists in power? What does the future hold for your country?” And he replied, “I don’t know – all I know is that now I can say I have a future.”

The foreign media are the first observers of history. They’re the first to witness events that are shaping the course of history. Whether it’s a small or large crisis, these are the moments that fall within the job description of foreign journalists covering international crises. Regardless of each outlet’s perspective, there’s only so many different interpretations of what is seen. This ensures a certain level of objectivity—after all, we’re not historians or analysts, and we don’t have all the answers. But our initial reports often set the stage for those who will tell the story again.