The Antonov’s cargo, parallels to previous arms smuggling cases, and its untracked flights through Greece.

A few minutes before 11 p.m. on July 16, 2022, residents of villages west of Kavala, saw a flash in the sky, followed by a powerful explosion. “I’m amazed it didn’t crash into our houses,” said Emilia Tsaptanova. “It went over the mountain, turned, and crashed into the fields.”

Moments earlier, the pilot of a Ukrainian Antonov An-12BK transport aircraft had reported damage to one of its engines. After the crash, all eight crew members were found dead. The aircraft had been carrying Serbian-made weapons and ammunition. An investigation by iMEdD and the Serbian network KRIK uncovered several shadowy aspects of this story.

The shipment was linked to a Serbian arms dealer allegedly connected to partners in Yemen and Liberia. The Antonov was scheduled to make stops in two countries bordering war zones, and another aircraft from the same operating company had previously been flagged in an arms smuggling case.

The accident was investigated in Athens by Greece’s National Aviation Investigation Agency and Railway Accidents and Transportation Safety (HARSIA), but two and a half years later, no official findings have been released. Meanwhile, Ukraine’s corresponding agency issued a preliminary report stating that the fatal flight—coded MEM3032—had taken off from Niš, Serbia, en route to Amman, Jordan. The aircraft was scheduled to make stopovers in Saudi Arabia and India before delivering its cargo to the Bangladeshi armed forces, according to the official account.

Upon entering Greek airspace, the crew reported a fuel leak and indicated they would return to Serbia. The aircraft made a 180-degree turn east of Mount Athos, but one of its engines appeared to catch fire. The pilot issued a distress signal and requested an emergency landing at Kavala Airport but was unable to reach the runway.

Ukrainian experts noted in their report that just a month before the crash, the same aircraft was involved in an accident at Poland’s RzeszówAirport. While being towed on the runway, it struck a lighting fixture with its right wing.

STAFF/EUROKINISSI

“Hazardous Cargo”

In the same report, Ukrainian officials noted that, on its final flight, the Antonov was carrying 12.1 tons of “hazardous cargo.” Greek authorities claimed they were only informed of this after the crash. Along with firefighters, a team of army explosive experts, including a mine disposal unit, were deployed to the site.

The wreckage site was cordoned off for several kilometers, and residents of nearby villages were advised to keep their doors and windows closed. A fire department spokesman stated that firefighters at the scene “experienced a burning sensation on their lips,” while the atmosphere was covered in white powder.

According Serbia’s then Defense Minister, Nebojsa Stefanovic, the aircraft was carrying at least 11 tons of Serbian-made weapons, including training mines. Officials and company representatives confirmed that it was also carrying mortar shells.

The weapons and ammunition had been manufactured by the Serbian state-owned company Krusik on behalf of a Polish company, which was listed as the official shipper in the cargo documents. The shipment, worth $600,000, was authorized under an export license issued by the Serbian private company Valir d.o.o. Investigations by KRIK and OCCRP suggest that the real owner of Valir is Serbian arms dealer Slobodan Tešić.

Hamas Weapons in Bulgaria

How a cache of weapons in southern Bulgaria is allegedly linked to a Hamas cell, planning attacks in Europe. iMEdD followed the trail of a man accused of being involved in the network.

The Serbs

Tešić was placed on the U.S. sanctions list in 2017 for corruption and bribery of high-ranking officials. He was later sanctioned by the UK as well. In 2013, reports revealed that members of the Serbian government had helped remove him from a UN blacklist, where he had been placed for allegedly supplying arms to former Liberian dictator and convicted war criminal Charles Taylor. Among other privileges he enjoyed, Tešić reportedly had the ability to purchase arms from Krusik at or even below production costs.

Tešić is described as the shadowy owner of Valir, the private company listed as the shipper of the cargo aboard the aircraft that crashed in Kavala. Valir was founded in 2019, with Stefan Cupković serving as its director for only the first few months. That same year, Cupković was also the official representative of a Belgrade-based company linked to Goran Andrić, a close associate of Tešić’s. After Cupković stepped down, he was succeeded by a Yemeni national believed to be part of the Tešić network. In a previous interview with KRIK and OCCRP, Tešić denied owning or controlling Valir. “This is clear, not only from official documents but also from the market itself, where it is widely known that I neither own nor control the company,” he said.

“In accordance with the restrictions I have at the moment, due to sanctions, this is my currently active and main role in the arms sector” he said, adding, “Also, in accordance with my age and position, it is no longer necessary for me to be the owner of a company or be operationally engaged in business. These 40 years, having made contacts all over the world, today I can open doors for others, and create business by connecting and helping many.”

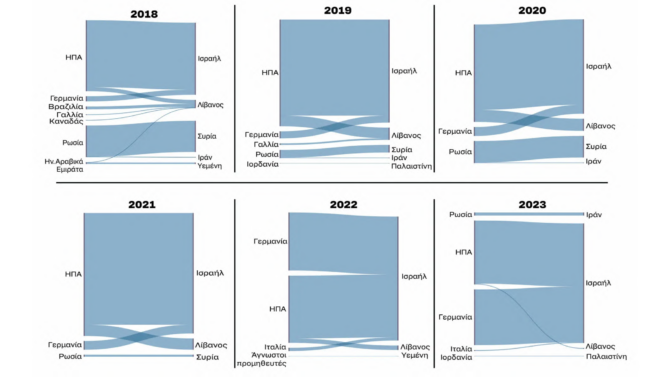

Armaments: Israel and the others

Data from the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI) on international arms transfers to Israel, Syria, Iran, Lebanon, Yemen and Palestine. What does the data on the quantity and origin of transfers show?

The Ukrainians

The second chapter of the Antonov crash story unfolds in Ukraine. The aircraft’s operator, under a long-term lease, was Meridian LLC, a company based in Kyiv. In the summer of 2009, one of Meridian’s aircraft landed in Kano, Nigeria, for refueling. It was carrying weapons and ammunition and was seized by local authorities on suspicion of smuggling.

“There were all (the) permits for this flight (…) There were no violations regarding either the plane or the cargo, or the documents,” a Ukrainian who was then the director general of Meridian, had said at the time. Records from Ukraine’s company registry show that he remained in the same position at least until 2020.

STAFF/EUROKINISSI

At the time of the Kavala crash, the Antonov’s registered owner was DS Air Inc, a Cypriot company. Another Cypriot firm, Ledra Corporate Directors Ltd, was listed as its managing company. A lawyer serving on Ledra’s board was later sanctioned by the U.S. and the U.K. for alleged ties to Russian oligarchs close to Vladimir Putin.

Following the crash, Ledra was removed from DS Air’s records. DS Air then turned to a different company for management services. A representative of this firm told iMEdD that he was approached by a “Ukrainian partner of DS Air” seeking collaboration on company management and accounting. However, he declined the offer, considering DS Air a “high-risk company due to its involvement in arms transport.”

Representatives of both Valir and Meridian did not respond to written requests for comment.

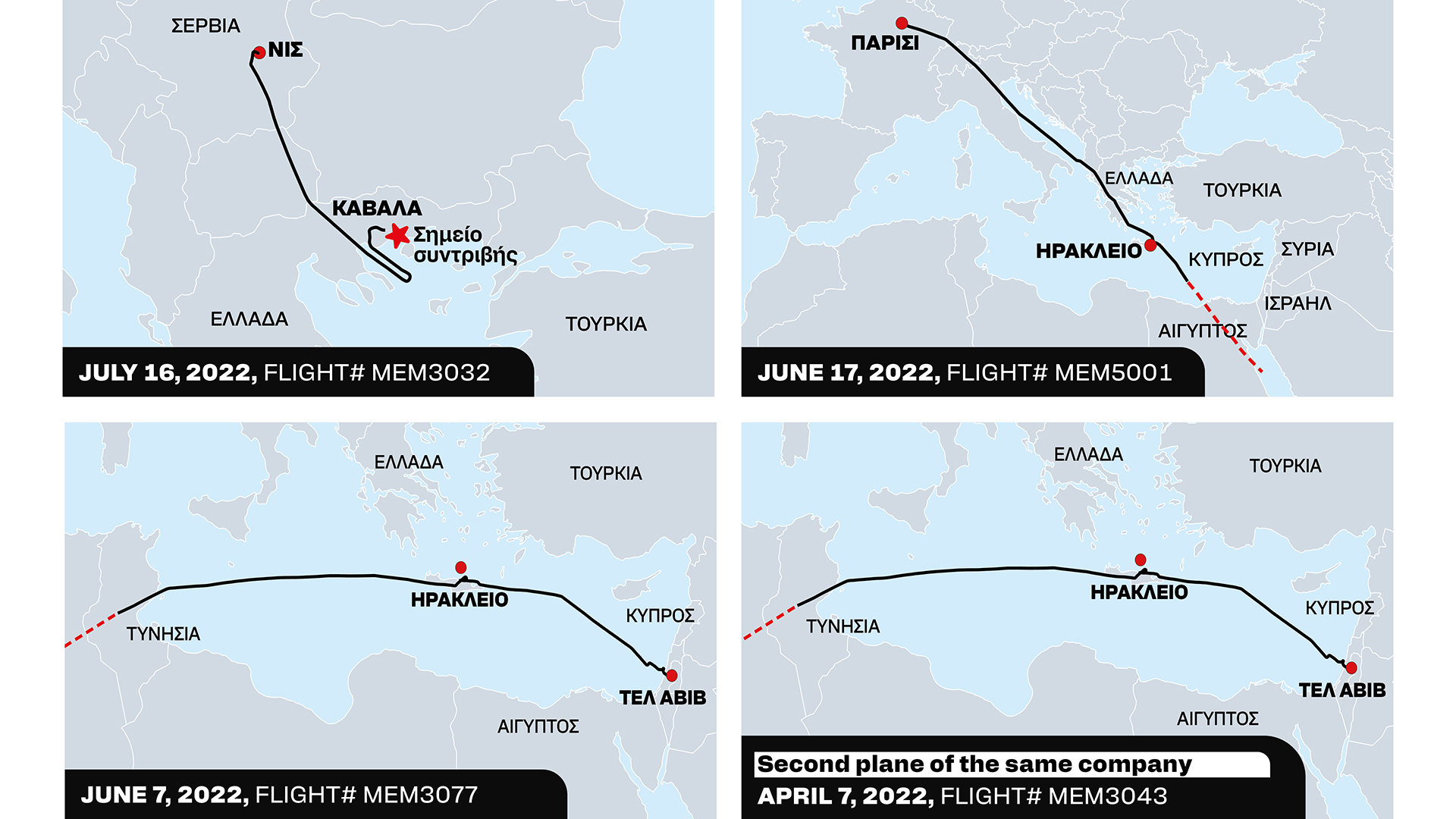

Antonov’s Trips to Greece and tracking data gaps

A search of the flightradar24 database reveals that, just weeks before the crash near Kavala, the Antonov had landed twice in Heraklion, Crete, for unknown reasons. On both occasions, it remained on the island for about an hour. Its exact route before and after passing through Greece remains unclear.

On June 17, 2022, the Antonov flew from Paris to Heraklion, after which its tracking signal disappeared over the Libyan Sea. Ten days earlier, on June 7, 2022, the same aircraft landed in Heraklion before flying to Tel Aviv. Its origin on that flight is unknown, as tracking was lost over the Algerian-Tunisian border. In April of the same year, another aircraft from the same airline followed an identical flight path, also with unexplained gaps in its tracking data.

A flightradar24 spokesperson, responding to written questions, explained to iMEdD that this type of aircraft relies on an ADS-B system to transmit location data. “The first piece of the puzzle is that the aircraft was flying over areas with few signal receivers,” he noted.

The second piece of the puzzle is altitude. Coverage from receivers on the ground is stronger at higher altitudes—”think of it as an inverted cone,” the spokesperson said. This particular aircraft type flies at a relatively low altitude, around 25,000 feet, meaning receivers need to be nearby to detect the signal. “Generally speaking, an aircraft at that altitude and in that geographic location (the blind spots on the map) is out of coverage.”

Additional reporting in Serbia: Bojana Jovanovic – KRIK

Translation: Anatoli Stavroulopoulou.

Read all articles and analyses of the Special Report: “Armories of the Middle East” here.

This article was first published on Feb. 22 by the weekend edition of the newspaper “TA NEA”.