Burnout isn’t just a workplace issue in journalism. It’s a press-freedom problem. Experts in journalists’ mental health explain what’s driving the crisis and what needs to change.

Illustrations: Evgenios Kalofolias

Accommodating journalists is in — or you’re out

Journalism’s future depends on balancing excellence with compassion and accommodations for those colleagues facing health issues.

“I was fed up and bogged down. Of course, you say other people are, too, and they keep going on. But if your job is to report on the war, you’re very apt to begin writing unconscious distortions and unwarranted pessimisms when you get too tired. Personal weariness became a forest that shut off my view of the events around me.”

These are the words of Ernie Pyle, an American reporter during World War II.

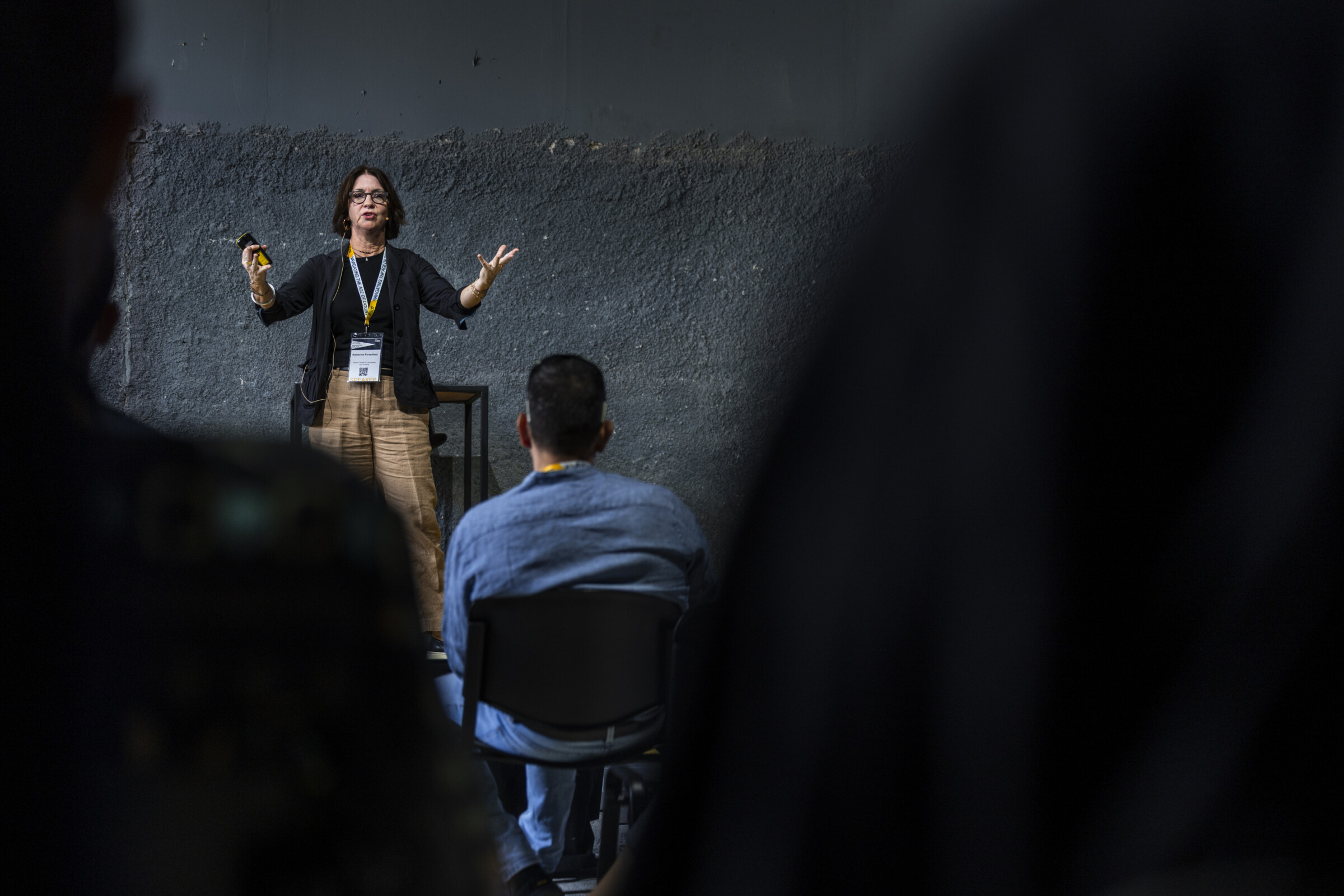

Standing on the stage of the International Journalism Forum in Athens in September 2025, Bruce Shapiro, Director of the Global Center for Journalism and Trauma, read them aloud to the audience during his presentation on burnout in today’s newsrooms.

Pyle’s reflections, written eight decades ago, sound today like an early anatomy of burnout: the creeping fatigue that blurs perception and numbs compassion, even for those trained to bear witness.

Today, journalists are still running on empty. They face relentless deadlines, work long hours, often witness trauma, and sometimes endure their own. Harassment follows them online and in the streets, while government pressure and censorship tighten around them.

A new survey conducted by the Taktak Media project, supported by the European Union, provides a stark snapshot of the invisible crisis facing journalists across Europe. Six in ten journalists say they have experienced burnout, and nearly as many (62%) report job insecurity and the need to take on extra work to cover basic living costs.

What is burnout?

Burnout is distinct from everyday stress. It signifies going “beyond one’s limits” into a state of crisis.

[Burnout] can destroy a journalist’s career, which I view not only as a personal tragedy for the journalists involved, but as a loss to press freedom

Bruce Shapiro, Director of the Global Center for Journalism and Trauma

The World Health Organization classifies burnout not as a medical disorder, but as a workplace phenomenon. It is the result of chronic stress that hasn’t been successfully managed. In its latest disease classification, the WHO describes it as a state marked by exhaustion, a growing sense of detachment or negativity toward one’s job, and a decline in professional effectiveness.

Bruce Shapiro told iMEdD that journalists are “the Olympic athletes of stress.” A former reporter himself, he added a warning: even athletes, eventually, collapse.

A journalist’s brain can falter when exposed to excessive stress, Shapiro said. “And at the far end of that, if there is too much stress at too high a level for too long, reporters can really lose their professional capacity, their motivation, and their ability to meet deadlines.”

For Shapiro, the stakes of burnout go beyond individual exhaustion. “You want to pay attention because it can destroy a journalist’s career, which I view not only as a personal tragedy for the journalists involved, but as a loss to press freedom. A journalist who is sidelined by psychological injury is silenced as effectively as if imprisoned,” he told iMEdD.

Stress vs trauma

“Notice your reactions, Dr. Kate Porterfield advised participants at iMEdD’s International Journalism Forum, where she led a workshop on “Coping with Stress, Trauma, and Burnout on the Job.”

A clinical psychologist with 25 years of experience working with individuals affected by trauma, persecution, and violence, including journalists and human rights professionals, and a trainer with the Global Center for Journalism and Trauma, she emphasized that stress and trauma are not the same. Both, she noted in her workshop, can affect “every aspect of human functioning: biological, psychological, and social”.

Trauma comes from exposure to disturbing or frightening material, such as seeing, hearing, or reporting on upsetting events, and it triggers a physical and emotional reaction.

“This body of ours is a survival mechanism. I always say the body is wired to survive… and that wiring is actually quite amazing and quite effective. But that wiring can leave an imprint after it’s had to activate too much,” she explained to iMEdD.

Recognizing the signs of burnout

Burnout, by contrast, Dr. Porterfield added, stems from the demands of the job itself: repetitive tasks, lack of control, or feeling stuck and undervalued.

“When someone feels drained for months on end, not just a week or two, [burnout] starts to show,” said Kim Brice, co-founder and coaching director of The Self-Investigation, a nonprofit focused on journalists’ mental health and workplace resilience, speaking to iMEdD. Journalists may struggle to get through daily tasks, feel unlike themselves, and even brush off repeated concerns from friends and family. “These are all signs that burnout has set in. “Yet, people experience burnout in different ways. It is not a clear-cut,” Brice added.

Burnout doesn’t stop at the office door. “We bring our whole selves to work,” she said. “We can separate home and work in our minds, even physically, but our bodies and our emotional state don’t recognize those boundaries.”

Parenthood, personal trauma, neurodivergence, and even hormonal shifts can all shape how people respond to stress, often deepening or accelerating burnout.

When someone feels drained for months on end, not just a week or two, [burnout] starts to show

Kim Brice, co-founder and coaching director of The Self-Investigation

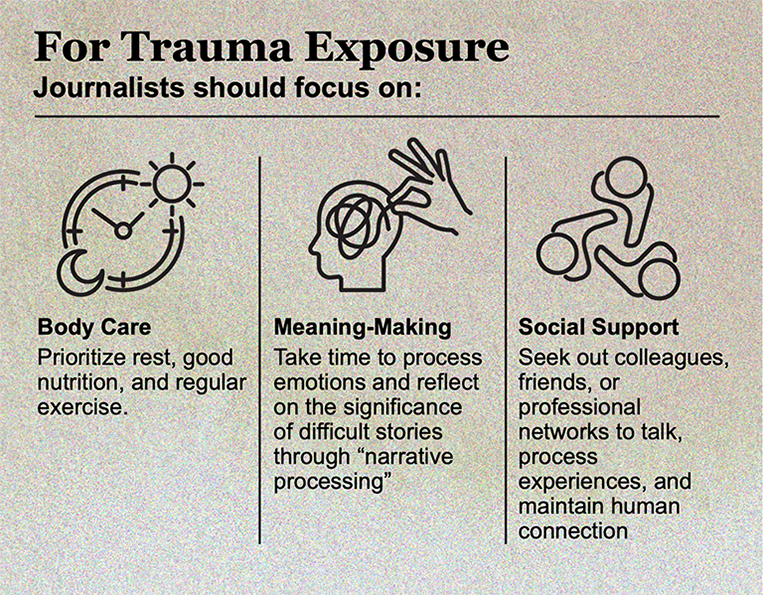

Coping Strategies

Journalists need two separate “toolkits”, said Dr. Porterfield. One for managing traumatic material in the field and another for coping with workplace stress and fatigue. While the tools can overlap, understanding the difference helps journalists protect themselves and recover effectively, she adds.

A collective response

Dr. Kate Porterfield pointed to peer support as an especially effective approach for professions regularly exposed to trauma, such as police officers and firefighters. “It’s interesting,” she adds, “how in many fields, people would rather open up to a peer than anyone else.”

Peer support has helped normalize experiences and has connected people to further help when needed. Journalists, who often pride themselves on being “tough,” will benefit from opening up more to colleagues who understand the unique pressures of their work, she adds.

In 2023, the Netzwerk Recherche Helpline, a peer-support-helpline for journalists fighting mental health issues, debuted in Germany. The initiative, a collaboration between the Dart Centre Europe and Netzwerk Recherche, the German Association of Investigative Journalists, is a successful example of peer support. It is free of charge and is run by trained fellow journalists, skilled in psychological first aid.

In March 2025, they introduced an English-language service for foreign journalists based in Germany.

Jelani Cobb on freedom of speech, the Press, and White House reporting

Jelani Cobb, Dean of the Columbia Journalism School, author, and longtime staff writer for The New Yorker, speaks to iMEdD about academic freedom in the United States, the challenges facing the press today, so-called “Trump coverage,” and the public interest as journalism’s enduring mission.

Managing burnout as a manager

“Burnout is a silent killer of people’s careers,” Bruce Shapiro told iMEdD, adding that the social environment of the newsroom plays a crucial role for those dealing with burnout and trauma.

As he noted, studies show that reporters and news teams covering traumatic events face a higher risk of developing post-traumatic stress disorder when newsroom management is lacking, underscoring the importance of supportive leadership and workplace practices.

“I grew up at an age when it was normal to throw typewriters across the newsroom if you were angry,” he said. “That doesn’t mean newsroom leaders should act as therapists. On the contrary, their role is to manage calmly, deliberately, and with trust-building at the core.”

He recommends that newsroom leaders support their teams before, during, and after difficult assignments, while organizations also focus on fair pay and overall working conditions.

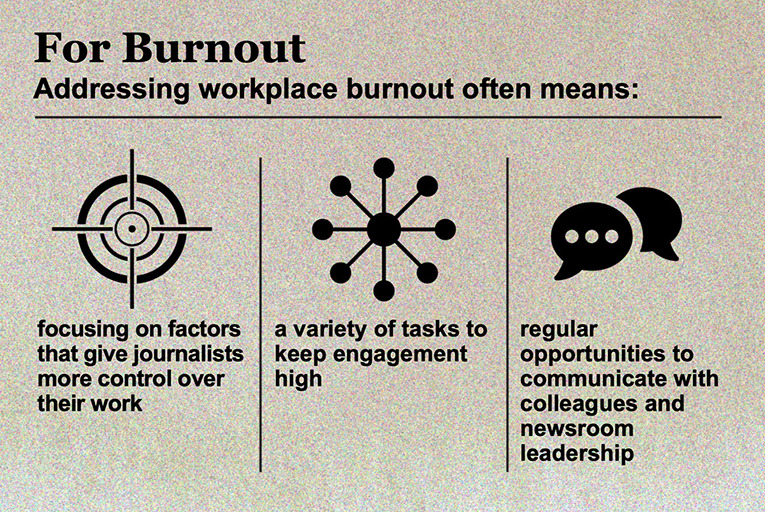

For Kim Brice, peer support is as essential among newsroom managers as it is for individual journalists. “We see that many middle managers don’t take the time to really sit and reflect together,” she added. “So, creating reflection time within any management level is really key. (…) Within their peer group, there are different ways of calibrating their day and setting boundaries during the day.”

She also pointed out that people management in the newsrooms stumbles upon a broader structural challenge. Many newsroom managers are effectively doing two jobs: leading coverage and supporting people. “What often happens is it’s like these managers have two shifts, the news shift and the people management shift. And often there’s more time spent on news and less time on people.” That imbalance is partly the result of how newsroom leadership pipelines work: people are promoted because they excel at reporting, not because they’ve been prepared to supervise others. “I think management training [in newsrooms] is key,” she added.

Managers must also pay attention to certain groups of journalists who may be more vulnerable to burnout due to biological, societal, and workplace factors. Newsroom leaders can help by cultivating an open environment and being trained to address these issues, including supporting colleagues with disabilities.

“Accommodations are often small, but highly impactful,” Brice noted.

This is a selection of resources on preventing burnout, coping with trauma, supporting recovery, and practical tips for newsroom managers and leaders.

Additional Resources:

Coping with stress, trauma and burnout on the job (Dr. Kate Porterfield tipsheet from iMEdD’s International Journalism Forum) – Link

On burnout:

- Bonn Institute – A one-page Self-Check Mental Health for Journalists and a website that includes several resources – Link

- Headlines Network – A guide on the recognition and prevention of burnout – Link

On trauma:

- A collection of videos, study guides, and tip sheets from the Global Center for Journalism & Trauma, CBC/Radio-Canada, and the Canadian Journalism Forum on Violence and Trauma – Link

- Reporters Without Borders (RSF) – A five-part series on the effects of psychological trauma on journalists – Link

For managers and teams:

- Coalition Against Online Violence – Resources for social media teams, fact-checkers, and open-source reporters – Link

- American Press Institute – How news leaders can foster psychological safety and a resource guide – Link

- The Self Investigation – Mental Health Leadership Toolkit for Fact-Checkers – Link