How do you investigate obstetric violence when official data doesn’t exist? In Serbia, two investigative journalists turned to the digital crowd to collect stories of survivors. How can crowdsourcing serve the reporting of trauma-laden stories? Two experts weigh in, offering critical insights on building trust and care into the reporting process.

Watch your language

Journalists must choose words carefully, ensuring that their coverage informs accurately and respects the dignity of all people.

In January 2024, a social media post by a Serbian woman went viral. It alleged that her newborn died due to obstetric violence. She described physical abuse during childbirth, including beatings and forced labor. An autopsy report confirmed the claims, and the doctor was arrested and detained.

In February, investigative journalists Teodora Ćurčić and Dina Djordjević from the Center for Investigative Journalism of Serbia (CIJS) decided to look deeper into the issue.

“It really gained a lot of attention,” says Ćurčić to iMEdD. “It’s a topic that’s widespread but not reported on.”

Ćurčić and Djordjević decided to report on the story by posting a secure questionnaire link on social media and partnered with local influencers to amplify its reach. Within a month, more than 1,000 women from across Serbia came forward.

They entrusted them with deeply personal stories—many for the first time.

The story was published in February 2025 on the investigative network’s Center, followed by a second part focusing on the cases that have been brought to justice but remain unresolved.

Why crowdsourcing

Ćurčić and Djordjević say crowdsourcing wasn’t a strategy—it was the only viable path forward.

The team filed 100 FOIA requests with 100 courts and prosecutors’ offices across Serbia, seeking details on past cases and systemic issues. Although they received close to 30 responses, those didn’t provide much information since just a few formal complaints had been filed.

Very quickly, they realized that most survivors of obstetric violence had never come forward, let alone had filed official complaints.

“There weren’t a lot of documents, and we couldn’t build a story on that alone,” Ćurčić says. “We realized we needed to hear directly from women, so we asked them to share their experiences.”

A few months into the investigation, the team launched the questionnaire.

Creating a safe space

Crowdsourcing allowed the team to “create a safe space, where women could finally speak openly, knowing they were heard,” adds Ćurčić.

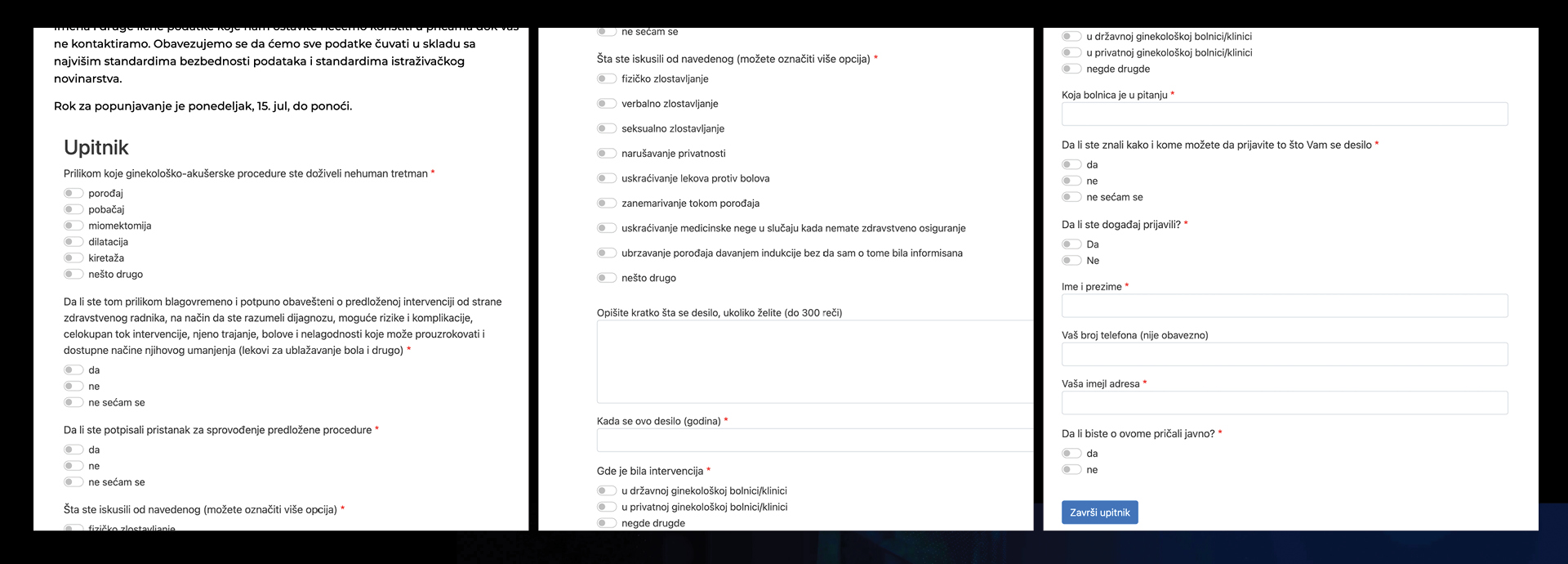

Building on previous investigations into sensitive topics, the World Health Organization (WHO)’s definition of obstetric violence, and having consulted with local legal experts on the topic, the team drafted the questionnaire carefully.

The survey began with the simple question: “What happened to you?” Participants were free to share their experiences in as much detail as they wished. Some offered brief accounts, while others wrote extended accounts.

After sharing their stories, the women were asked more specific questions: “Where did the incident occur?”, “Was it in a state or private hospital?”, “In which city?”

In the second part of the survey, participants were asked whether they had reported the incident to the authorities and, if not, what had prevented them from doing so. They were also given the option to indicate whether they would be willing to speak publicly, either anonymously or by name. What stood out, however, was that just 3% of the women who responded to the survey had ever reported the incidents to Serbian authorities.

More than 150 women also came forward, she adds, wishing to put their names to their stories.

Exposing the patterns

The essence of most stories couldn’t be verified—no witnesses, no evidence. But certain basic elements of their identity could.

For women who had not reported their cases to the authorities but completed the questionnaire and provided contact information, the team followed up with phone interviews. This allowed them to verify key details, such as the woman’s location, the hospital involved, and other basic information.

“Where legal proceedings were involved (such as cases that reached court or the prosecutor’s office), we requested full documentation, which sometimes included expert analyses or testimonies from other people,” says Ćurčić.

“Still, we couldn’t fact-check these stories in the traditional sense, and ultimately, we decided to trust them and share their voices.”

In the final stage, the reporters circled back to the experts. Some stood by the system, so the team had to sort through mixed views.

Why crowd-driven journalism works—and when it doesn’t

Crowdsourcing has been part of journalism for nearly two decades.

Jeff Howe coined the term in 2006 to describe an open call to the public for ideas, expertise, or information. But when it comes to sensitive issues like trauma and abuse, this method demands careful handling.

Speaking to iMEdD, Nils Mulvad, investigative journalist, trainer, and co-founder of the Global Investigative Journalism Network (GIJN), emphasizes the importance of trust and clarity when using crowdsourcing to report on sensitive stories.

“People won’t share very sensitive information unless it’s extremely important to them—and even then, they need to trust who they’re sharing it with.”

He says credibility is key.

Respondents are more likely to participate when they recognize the journalists involved or the media outlet’s name. Personal contact helps, and using secure, well-explained tools builds confidence.

Mulvad also advises caution when designing questionnaires:

- Avoid asking for data that’s available elsewhere, such as official statistics.

- Design clear, structured questions with multiple-choice answers when possible.

- Be transparent about who owns and handles the data, and how privacy is protected.

He also reminds journalists that responses to a crowdsourced questionnaire should not be treated as statistically representative.

“You can’t say 1,000 responses represent the whole population. But you can report what patterns emerge from those 1,000 people — and use powerful individual cases to validate those patterns.”

When publishing the story, says Mulvad, include a methodology note explaining how the survey was conducted.

And be open to criticism:

“If someone raises concerns, take them seriously. Re-check your conclusions. If they’re right, say thank you—because that makes your reporting stronger.”

How to interview trauma survivors

Reporting on trauma-sensitive stories can be challenging. Journalists need to be well-prepared to report with fairness, empathy, and accuracy. Irene Caselli, Senior Consultant at the Early Childhood Journalism Initiative of the Dart Center for Journalism and Trauma, shares three key tips for reporters working in this space.

#1 Be prepared

For this kind of reporting, being prepared is crucial. “It’s essential to understand how these stories affect both the reporter and the interviewee, and how those effects can ripple back to us,” says Caselli.

#2 Use “The Frame” to ask questions

The “Frame” is a tool created by Kate Porterfield, a psychologist at the Dart Center with extensive experience interviewing trauma and torture survivors, including children. It helps journalists practice asking questions that employ safety, control, reflecting back and closure.

The goal, says Caselli, is to create a safe environment where you can explore difficult topics but always know how to step back.

For trauma survivors, regaining control is also key. “Offering them the option to choose how the interview goes can help restore agency,” says Caselli.

Reflection is a powerful psychological tool. Instead of saying, ‘I know how you feel’—which we often don’t—it’s more about acknowledging their experience. For example, ‘I hear you say that it was very difficult for you.’ “This approach helps validate their feelings and makes them feel seen and heard,” she adds.

At the end of the interview, it’s important to close properly. Often, as journalists, we focus on asking questions and moving on, says Caselli, but we need to ensure the interviewee feels heard and validated. “Let them know the impact their sharing has had and reassure them about how their story will be handled.”

#3 Think about the language

The words we choose to describe people are incredibly important, says Caselli. “We need to be mindful of the language we use around victimhood and survivorship. These are key tools that should always be considered in such sensitive discussions.”

Resources for journalists investigating sensitive issues

Trauma Aware Journalism -Trauma Interviewing A practical framework to minimize harm when speaking to people affected by trauma. https://www.traumaawarejournalism.org/trauma-interviewing

The Dart Center for Journalism and Trauma

Training, tip sheets, and ethical guidelines for trauma-informed reporting.

https://dartcenter.org

First Draft News – Guide to Verifying Online Information

Essential when collecting testimonies from the public. https://firstdraftnews.org/articles/verifying-online-information-the-absolute-essentials/

Columbia Journalism School – Guide to Crowdsourcing https://www.cjr.org/tow_center_reports/guide_to_crowdsourcing.php