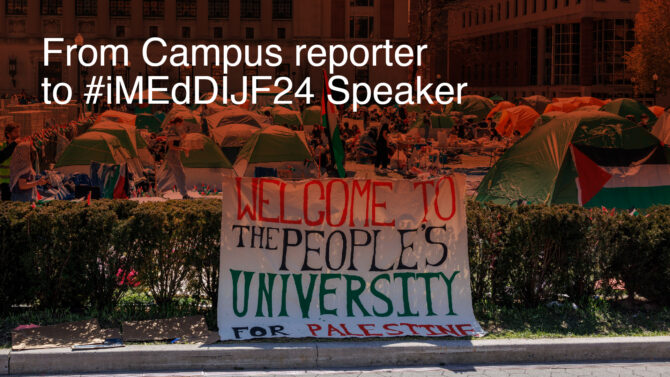

At Columbia and Wits Universities, campuses erupted as student protesters clashed with their institutions. Soon after, both universities showed a greater focus on security and control. Ruby Delahunt, a journalism student at Wits, examines the impact of the protests on the institutions and the student journalists covering the events for the 2024 iMEdD International Journalism Forum’s Pop-up Newsroom.

Columbia University’s young reporters: from covering campus protests to Greece

These young journalists found themselves on the frontlines of the 2024 Columbia University pro-Palestinian encampment, balancing the roles of students, activists, and reporters. Now they travel halfway around the world at the iMEdD International Journalism Forum to present their work to a room of top-tier journalists they look up to. Columbia University Graduate student Gaia Caramazza, who also covered the Columbia University protests talked to Editor-in-Chief, President, of the Columbia Daily Spectator Isabella Ramírez and Palestinian freelance fournalist and Jordan Media Institute faculty member, Jude Taha about the challenges they faced, for the Forum’s Pop-Up Newsroom.

It was April 2024 at Columbia University in New York City. The lawns were packed with dozens of green tents. Students were protesting against the war in Gaza. They gathered in groups for teach-ins and prayers, all while glancing over their shoulders in fear. Hamilton Hall – one of Columbia’s academic buildings renamed Hind’s Hall by protesters in memory of Hind Rajab, a six-year-old Palestinian girl killed in January 2024 by Israeli forces in Gaza City – was glittering in the setting sunlight. Police cars were lined up bumper to bumper around the campus, keeping the students inside and the media out.

Nearly a decade ago, student protests erupted at Wits University over tuition hikes. It was September 2016. Students blocked all entrances to the institution, effectively shutting it down. These were much larger and louder protests than previous ones in recent years. The Great Hall was covered in shards of glass. Police and private security with sunglasses were patrolling the quad, fingers curled around the trigger of their weapons. Student activists prowled on the sidelines, bricks in hand, undeterred by this new presence. Their fight was too important to give up on. Within days, the protest movement had drawn tens of thousands of students from universities across the country.

Both universities soon cut access to their campuses. Student journalists found themselves with unique access and insights into the protests. On all fronts, however, they faced difficulty navigating the field, a challenge that did not stop them from continuing to report courageously.

Columbia and Wits University Protests

Young Journalists Amid Campus Protests

Pheladi Sethusa was a TV news producer during the 2016 #FeesMustFall protests that shook South Africa, and a recent graduate of the Wits University journalism program. “It wasn’t my first time covering protests on campus related to fees, but it was the first time I had seen such a significant swell in the number of students on the ground and their sustained action over days and weeks”, Sethusa said. The campus she had called home for years had turned into a battleground, but she was expected to report on it impartially, like any other ‘outsider’ journalist. She knew the people involved and sympathized with the cause quite intimately and passionately.

At Columbia, young journalists were expected to do the same thing, and in the face of even more intense violence and politicking. Journalists Anna Oakes and Jude Taha, freelance journalists and graduate students at Columbia Journalism School at the time, were pulled in all sorts of directions as they tried to separate themselves from the student body and report objectively despite being so close to the issue. “I did have very meaningful and deep relationships with the students who were protesting,” Taha said, but she insisted on making it known she was acting in her capacity as a journalist, even when this made the story more challenging to tell. The two journalists looked out at the iMEdD 2024 International Journalism Forum audience with quiet humility while detailing how large news organizations attempted to “hijack the narrative” of the protest and exploited their positions as young reporters who had attended Columbia and knew the protestors.

Oakes and Taha spoke at the Forum alongside their colleagues and Columbia Spectator staff, Amira McKee and Isabella Ramirez, and Columbia Professor, Nina Berman, at a panel entitled “Lessons from the students: How Columbia’s reporters covered the pro-Palestine campus protests”. The four young women discussed the bizarre situation they faced in becoming primary news reporters, as well as the struggle of being exploited by major media companies whilst also not being taken seriously by law enforcement and university faculty – in both cases due to their age and their ‘student’ label.

Taha commented that many media outlets used the Columbia journalists “as fixers in order to get their stories out”, rather than taking them seriously as journalists in their own right. Additionally, she was often “lumped in” with the protestors due to her Palestinian heritage by major outlets. “Instead of giving me my agency as a journalist”, she said, media outlets just wanted to use her as a commentator for the protestors.

In the same vein, Oakes shared that India Today requested her to find proof of Kashmiri nationalism on campus, and that other news outlets urged her to support the false claim that Jewish students were kicked off the campus during the Pro-Palestine encampment.

At both Wits and Columbia, it was student journalists who got booted off campus and blocked from covering the protests. Isabella Ramirez, editor-in-chief of the student paper, the Columbia Daily Spectator, was forcibly removed from campus by the New York Police Department (NYPD) along with hundreds of other students and had to fight tooth and nail to be allowed back.

Wits was no different, Sethusa said.

For some student reporters, covering the #FMF protests “encouraged their burgeoning careers, while others were left well and truly traumatized by the events”. From being a student journalist to now being a mentor to journalism students, she has seen how the university landscape has shifted since those fateful protests.

The Battle for Free Expression

After years of escalating racial tensions, rising fees, and dissatisfaction with government inaction, the #FMF movement represented a wide range of students who wanted change in the structure of society. Before 2016, South African universities were highly colonial environments, and the protest movement called for the total decolonization of the syllabus. The resistance students encountered only ignited their fire, and #FMF turned into a battle for control of campus between students and the police.

The explosion of brutal force that police and private security unleashed against Wits students was unparalleled. To ensure it never happens again, and certainly that it never makes the news again, securitization on campus has skyrocketed.

“Wits is a fortress now, and any time a whiff of protest bubbles [up], private and public law enforcement are unleashed on peaceful protestors” Sethusa explained. Following the #FMF protest action at Wits has been largely muted and minimal, which Sethusa agreed was the case. “I think students realized that they are truly on their own and risking life and limb for ideals that fell short in the face of systemic might, was just not worth it”.

During a Q&A session after the panel, I asked the iMEdD panelists whether that was the case at Columbia. They agreed: the campus is no longer an open, green space for New Yorkers to escape to, but an enclosed fortress with ID checks, an overbearing security presence and broken trust between students and the university body. “The university was caught off guard by the encampment, Isabella said, and so there have been “many measures put in place to prevent a similar situation from happening”.

After the #FMF protests, Wits issued a statement affirming their support for peaceful protest. Also in that statement, they laid down a lengthy list of rules around protesting, later also declaring only certain parts of campus to be designated for protesting.

Columbia issued a similar statement this September, reiterating their support for free speech, protests, and demonstrations – “as long as these do not substantially disrupt the University’s academic activities.” Their list of rules and regulations was even lengthier than the one published by Wits.

Student Journalism

Students at both institutions – including myself – will continue to fight, because it is what we do. In the face of misrepresentation, endangerment, and violence, student journalists at both universities will continue to report on the fight. Both journalists and students are some of the most vulnerable people in society. When they are stepped on, that foot crushes down on freedom, safety, and truth. It is a massive success, and a testament to their integrity, that student journalists across the globe still rise from the ashes and refuse to be silenced.

On September 27, 2024, Columbia erupted once more in protest of the bombing of Lebanon, and Columbia Daily Spectator journalists agreed that they would not be intimidated into silence about the events. Wits’ student journalists of the class of 2024, of which I am a part, covered the Wits Pro-Palestine encampment without fear. Campus security always lurked on the sidelines, but the peaceful nature of the encampment was not enough to draw them out.

You can re-watch the discussion here.

Check out all Pop-Up Newsroom 2024 stories here.