Greek and foreign correspondents in Beirut describe what journalists planning to enter the war zone need to know.

“At some point in our hotel in Beirut, five security service agents showed up. They asked us to follow them—the German journalist I work with and I. Before we left, I had just enough time to message our producer: ‘SOS, police are here.’”

Photojournalist George Moutafis has been working for the German Axel Springer Group (Bild newspaper, Welt tv) for the past few years and has reported from war zones and crisis countries around the globe. Recently, while covering Israel’s conflict with Hezbollah in Beirut, he found himself detained in a cell for at least 12 hours, some of which he spent blindfolded.

iMEdD spoke to Greek and foreign correspondents in Lebanon to document what journalists need to know when working in one of the world’s most volatile regions today.

Alexia Kalaitzi, an envoy for ERT and Kathimerini, emphasises an important distinction from the start: while there is an email for sending documents, it’s often best to be on the ground. “At the same time, there are neighbourhoods and suburbs of Beirut controlled by Hezbollah or other smaller groups,” she noted during a WhatsApp call that was interrupted multiple times due to limited coverage.

Understanding Hezbollah’s influence in the country is critical. “Hezbollah is an armed group that operates guerrilla-style tactics and is very sensitive to outsiders, especially given recent events involving people entering their areas to film. They do not allow foreign or local journalists to report from the southern parts of Lebanon where the conflict is unfolding,” a journalist who works for a major US media outlet, who spoke anonymously, told iMEdD.

In early October, a Belgian television crew was attacked while covering an explosion in central Beirut. The cameraman was shot twice in the leg, while the other two crew members were detained for hours and beaten by unidentified men who accused them of being spies. The Belgians had found themselves uninvited to the “wrong” place.

Local journalists working for foreign media—often referred to as “fixers”—are just as crucial as official accreditation. “There are both practical and ethical reasons for working with a fixer. You’re in a country at war. They are your eyes and ears,” explains Alexia Kalaitzi.

In the current crisis, a skilled fixer in Lebanon can earn at least $400 a day. While many are professional journalists, academics and members of civil society also take on this important role.

“Having a local fixer for someone who’s never been to Lebanon will help them understand how to respect the culture, respect the population, what’s acceptable, what’s not acceptable. This includes everything from permission to shoot and take photographs to how to interview people, it’s very important”, explains Nada Homsi, Beirut correspondent for The National, a UAE state-owned English-language daily newspaper.

“It’s also very important to pay the fixer well. It’s very important to make sure the fixer is ensured, that their safety is ensured, as much as the correspondent’s. Safety is insured. And unfortunately, I think the majority of news stations and news organisations don’t really do that”, Homsi adds.

Israel has a history of unsuccessful invasions of Lebanon. Will this time be any different?

Israel is now set to repeat its Gaza operations in Lebanon, with a view to reordering the Middle East in its own interests. But has it bitten off more than it can chew?

There are both practical and ethical reasons for working with a fixer. You’re in a country at war. They are your eyes and ears.

Alexia Kalaitzi, correspondent in Beirut for Hellenic Broadcasting Corporation (ERT) and Kathimerini newspaper.

The sources

Journalists in Beirut receive official positions from the Lebanese government through announcements in the local press. “At the same time, Hezbollah has its own English-language channel on Telegram,” explains Alexia Kalaitzi, an envoy for ERT and Kathimerini.

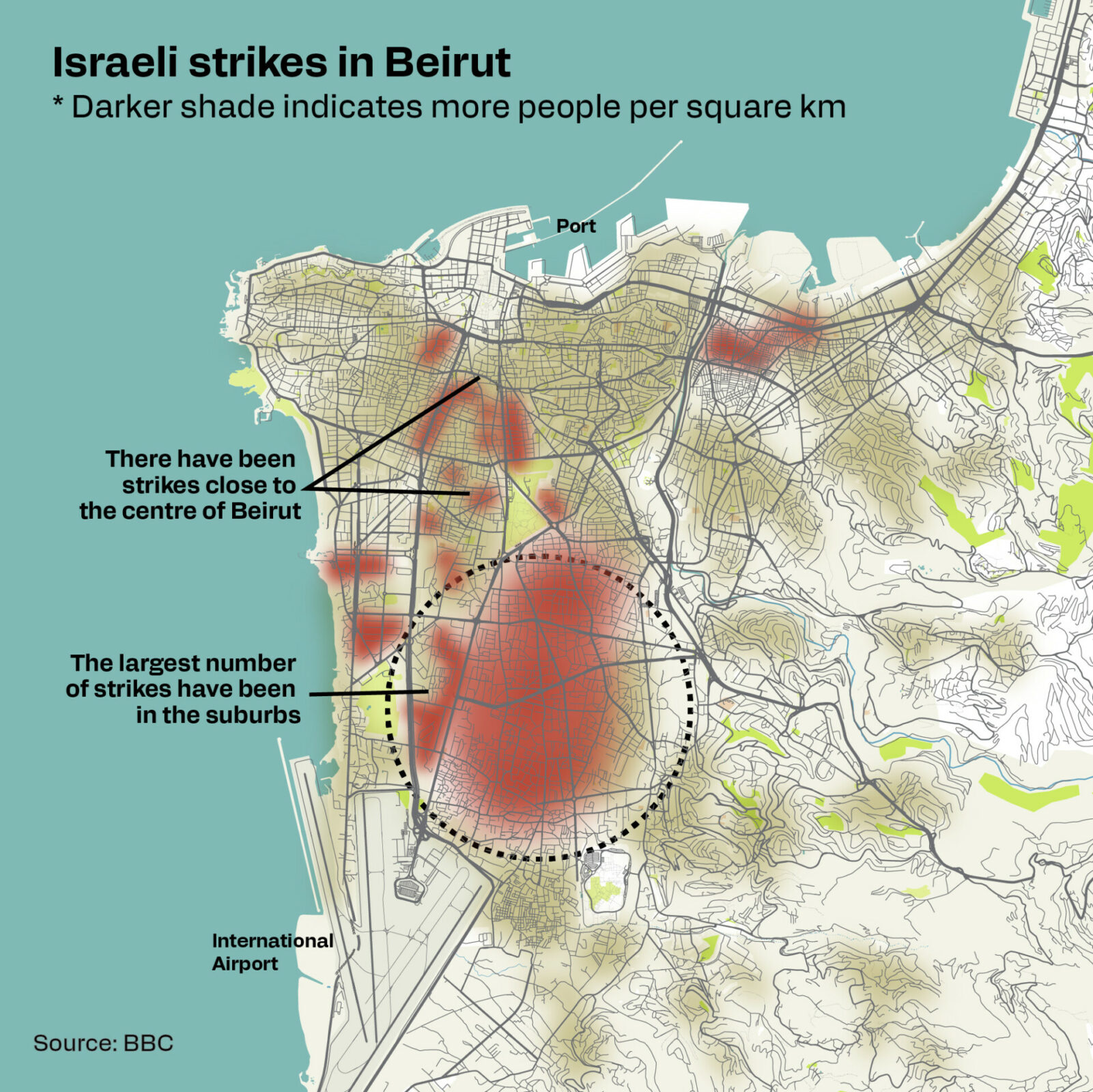

“In the first days of the Israeli attack, Hezbollah informed us that they would allow a one-and-a-half-hour visit to the southern suburbs of Beirut, specifically to the heavily bombed Dahieh area,” she says. Foreign correspondents took footage and conducted live reports, but they did not get statements from Hezbollah members. Afterwards, they left the area in the same coordinated manner and returned to the centre of Beirut.

There is no designated spot in the city centre where foreign crews set up for live broadcasts. One common solution is to use a room on a high floor of a hotel. There are two or three hotels where most foreign journalists stay, with the Hilton in the Hapthur district being the most popular.

Unlike in Ukraine or Israel, Lebanon has no sirens to warn of incoming strikes, no “alert” apps for mobile phones, and no war shelters for civilians.

Access to southern Lebanon requires permission from the Ministry of Information, the army’s intelligence service, and Hezbollah. “In WhatsApp chat groups, journalists share the phone numbers of Hezbollah officials responsible for communicating with the media. These are different from the contacts for the southern suburbs of Beirut. The process is informal, so even if a request is approved, it may take days or might never happen,” says Alexia Kalaitzi.

“It depends on which aspect of Hezbollah you want to communicate with. I mean, you know, we also have Hezbollah in the government and the parliament. So you have individual ministers and members of parliament that can be spoken to about their views. And then in terms of coordinating places, conflict areas that you want to go to, it’s usually better to coordinate with Hezbollah, both for our own safety as journalists and also because Hezbollah is very paranoid about security breaches, so they want to control their environment as much as possible”, explains The National’s Nada Homsi.

“The Lebanese government, which is not very effective and not very relevant, let’s say, in this conflict, is sharing its position, but those positions are not really very relevant. The position of Hezbollah as the armed group that is primarily engaged in the battle with Israel is far more relevant”, notes the journalist, who works for a major American media outlet and asked to remain anonymous.

“Many of its top leaders have been killed over the past days and couple weeks. However, there are still notices and press releases coming out from Hezbollah to understand their views, but certainly far less than before, as they’ve had to. I guess they feel they must be less transparent, be opaque, given all the successful infiltrations by the Israeli military against them”, he also noted.

One year and climbing: Israel responsible for record journalist death toll

One year in, Israel’s conduct of the war in Gaza has exacted an unprecedented and horrific toll on Palestinian journalists and the region’s media landscape.

Hezbollah tv

According to Reporters Without Borders (RSF), Al Manar is Hezbollah’s official TV channel. The most influential stations in Lebanon include LBCI, Al Jadeed, and MTV, which are owned by the Daher-Saad, Khayat, and Murr families, respectively. “The media is controlled by a handful of individuals directly linked to political parties or local dynasties,” RSF notes. In the 2024 Press Freedom Index, Lebanon ranks 140th out of 180 countries.

“Restrictions on journalists have tightened and press freedom has declined as Lebanon’s economic and political crisis has deepened. Since 7 October 2023 and the spillover of Israel’s war on Gaza, the situation has worsened considerably in this neighbouring country, with three journalists killed by Israeli strikes while covering tensions on South Lebanon’s border”, RSF note.

The National’s Nada Homsi adds: “Τhat’s when it became very apparent that although it was a low intensity conflict at that stage, Israel was essentially sending the message that nothing was off limits, including civilians, journalists or paramedics.”

At this stage, Lebanon requires coverage from the international media. American and European journalists receive a one-month visa on arrival at Beirut airport, the same duration allowed for journalistic accreditation. “Typically, you have to declare all your equipment in detail at customs, but we didn’t undergo such a check.’Sahafi’ (i.e., journalists), they said, and we passed,” explains George Moutafis.

RSF opened a regional press freedom centre in Beirut last March, with its long-standing partner in Lebanon, the Samir Kassir Foundation. The purpose of the centre is to provide journalists with a space where they can meet and work, and provide them with protective equipment, including helmets, bulletproof vests and first-aid kits, as well as psychological support, legal assistance and training in digital and physical security.

No one can know for certain when there will be a flight to leave the country, which is one of the most critical issues when reporting in a war zone. Correspondents and envoys advise that media outlets check whether any operations for civilian evacuations are being conducted by foreign governments, creating a “window of opportunity” for journalistic crews to board those flights.

It is impossible to cover both sides of a war without making one side unhappy. In crisis-ridden countries, journalists become a target priority.

Giorgos Moutafis, photojournalist & correspondent for the German Axel Springer group (Bild newspaper, Die Welt TV).

Blindfolded reporter

After the first few days in Beirut, photojournalist George Moutafis, along with the German journalist he collaborates with, found themselves in detention. In the preceding months, they had visited Israel, conducting exclusive interviews with Benjamin Netanyahu and the country’s president.

“We were blindfolded and taken in handcuffs to a Ministry of National Defense facility that looked like a barracks, from what I could see under the black blindfold,” Moutafis recounts to iMEdD. “We spent at least 12 hours in a cell, either standing or kneeling on the ground. They confiscated our cameras, cell phones, and cards. They interrogated us, asking what we were doing in Lebanon and who we had met during our previous visit to Israel.”

The interrogation was then taken over by an officer who spoke fluent English. “I told him that I understood national security was paramount for the country in question and that I fully respected that, but journalists must do their job, and we were not what they were looking for.”

“At one point, I was led alone to a room with a phone. On the other end was the Greek consul in Lebanon, Mr. Papadimitriou. He said, ‘Mr. Mutafi, we know where you are. Don’t worry, we are in contact with the people holding you. You will be free in a few hours.’ Only then did I calm down. The case was handled by the German government.”

“It is impossible to cover both sides of a war without making one side unhappy. In crisis-ridden countries, journalists become a target priority.” Lebanon is a country in disarray. All foreign correspondents told iMEdD that locals are afraid to speak – even those who know English prefer to communicate in their native language for fear of misrepresenting their statements. The second most prominent sound in Beirut today is the whirring of Israeli drones that continuously patrol the skies above the capital. Beyond operational reasons, this has a significant psychological impact on the people.

And then in terms of conflict areas that you want to go to, it’s usually better to coordinate with Hezbollah, both for our own safety as journalists and also because Hezbollah is very paranoid about security breaches, so they want to control their environment as much as possible.

Nada Homsi, correspondent in Beirut for The National newspaper.

“Fear protects me.”

iMEdD asked the correspondents if they are trained to work in war zones and whether they experience fear. “I’m trained to cover war zones, yes. I mean, I’ve covered war zones and I’ve received training and how to cover them,” replied the journalist covering the conflict for a major American media outlet. “The media organisation I am working for does provide security, what we call security advisors. They are not necessarily always coming out with me, but I have one”.

He also notes: “Look, anyone who’s in this situation would lie if they said they weren’t scared. That said, like in any conflict, there are ways to make yourself safe, even within a conflict zone. And this conflict, so far at least, has been mostly confined to certain areas. And if you’re not going to those areas, it’s certainly a lot safer. Again, that’s so far that might change, but of course we need to go into those areas. We’ll try to in any way, in order to tell the story”.

“It takes proper training for a field responder, both practical and psychological. I regularly undergo such training. I need a week of psychological preparation before I go to each war zone, and another week to decompress when I return. During the mission, I feel fear, and this protects me because fear makes you cautious,” explains Moutafis.

“I can’t say that I am afraid, but I am definitely more cautious,” says Alexia Kalaitzi. “Everyone is more cautious. On the day of the hit on Nasrallah, the owner of a shop, who was well-known to our fixer, asked us to set up further down the road. He didn’t want the live feed lights outside his door.”

“Any time you go to Dahieh, there’s a chance that you could get struck. In fact, yesterday I got really angry at my husband. He’s not a journalist, but he was helping his sister to get her stuff out of her house. She’s been displaced and he only went in for ten minutes, but they struck an hour later”, The National’s Nada Homsi tells iMEdD. “So, it is dangerous. You don’t know when it’s going to happen, but it’s not necessarily like a crippling fear”.