When the data needed for an investigation is not available, journalists turn to the public. We present four projects that were created with the participation and for the benefit of citizens. They are tools that may one day prove useful in your own reporting.

Crowd-Driven Journalism for Sensitive Stories

Crowdsourcing can be used as a valuable tool to investigate sensitive stories, when data do not exist. But it demands careful handling.

Sometimes, it really does take a village.

Since journalist Jeff Howe coined the term ‘crowdsourcing’ in Wired in 2006, newsrooms have increasingly turned to citizens for data, documents, and insights. Around the world, journalists have built crowdsourcing tools that let citizens share documents, flag problems, and map hidden stories newsrooms might otherwise miss.

From identifying local landlords in Hamburg, to mapping an uncharted floating slum in Lagos, to tracking air pollution in Nairobi with homemade sensors, to opening police misconduct records in California, these projects show what happens when journalists and citizens work together.

Each effort not only produced powerful reporting but also gave communities tools to advocate for themselves.

CrowdNewsroom: A tool that powers CORRECTIV’s investigations

In 2018, CORRECTIV, a German nonprofit newsroom connecting over 400 news outlets across Europe, launched the project Who Owns the City?, one of its first major crowd-sourced investigations, which began in Hamburg and later spread to other cities. The project was investigating the opaque housing market in Germany. When officials refused to release property records, reporters went straight to residents, using local media, pop-up offices, street events, and postcards. The result? About 1,000 tenants uploaded documents identifying their landlords to CrowdNewsroom’s platform.

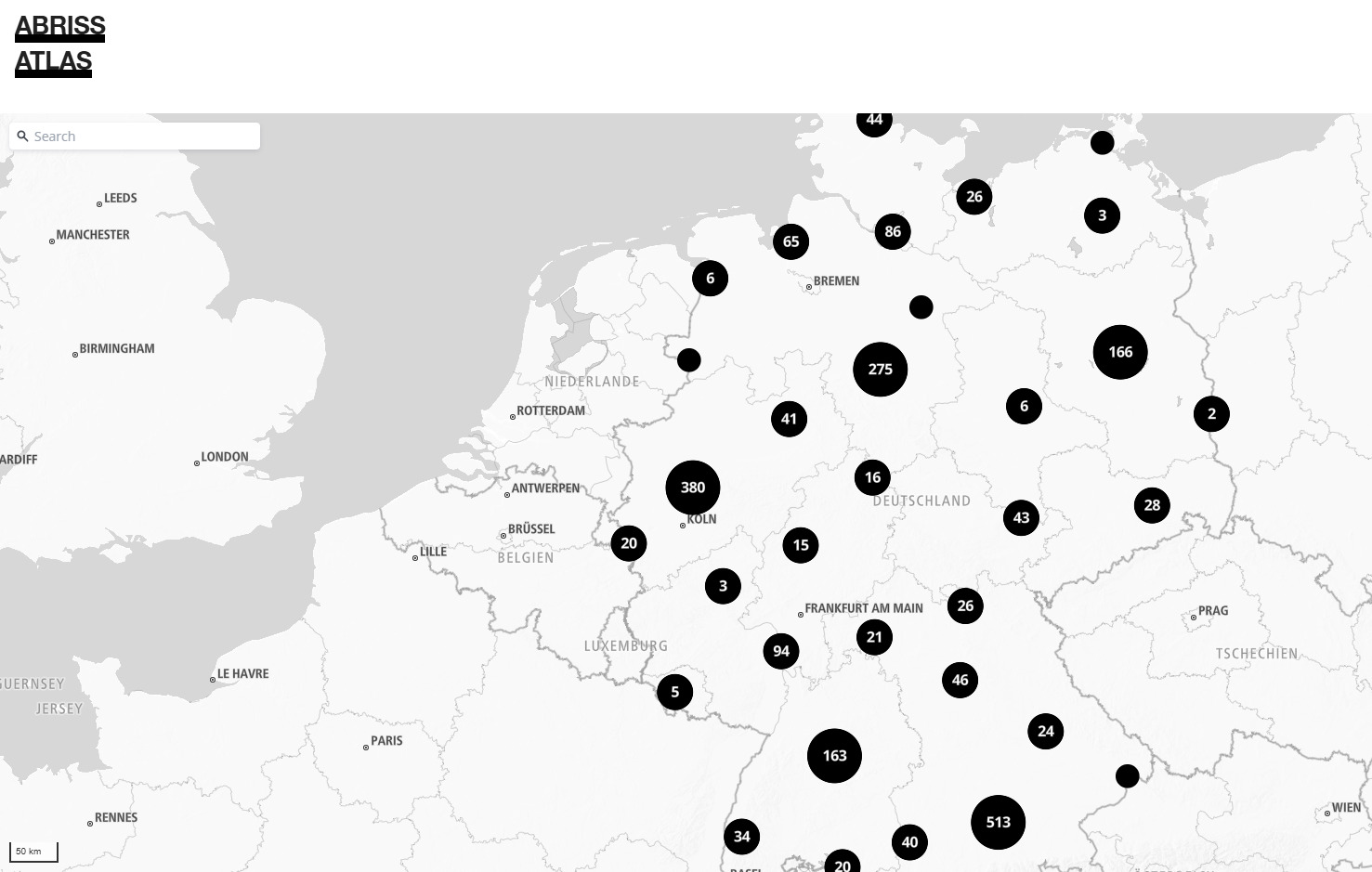

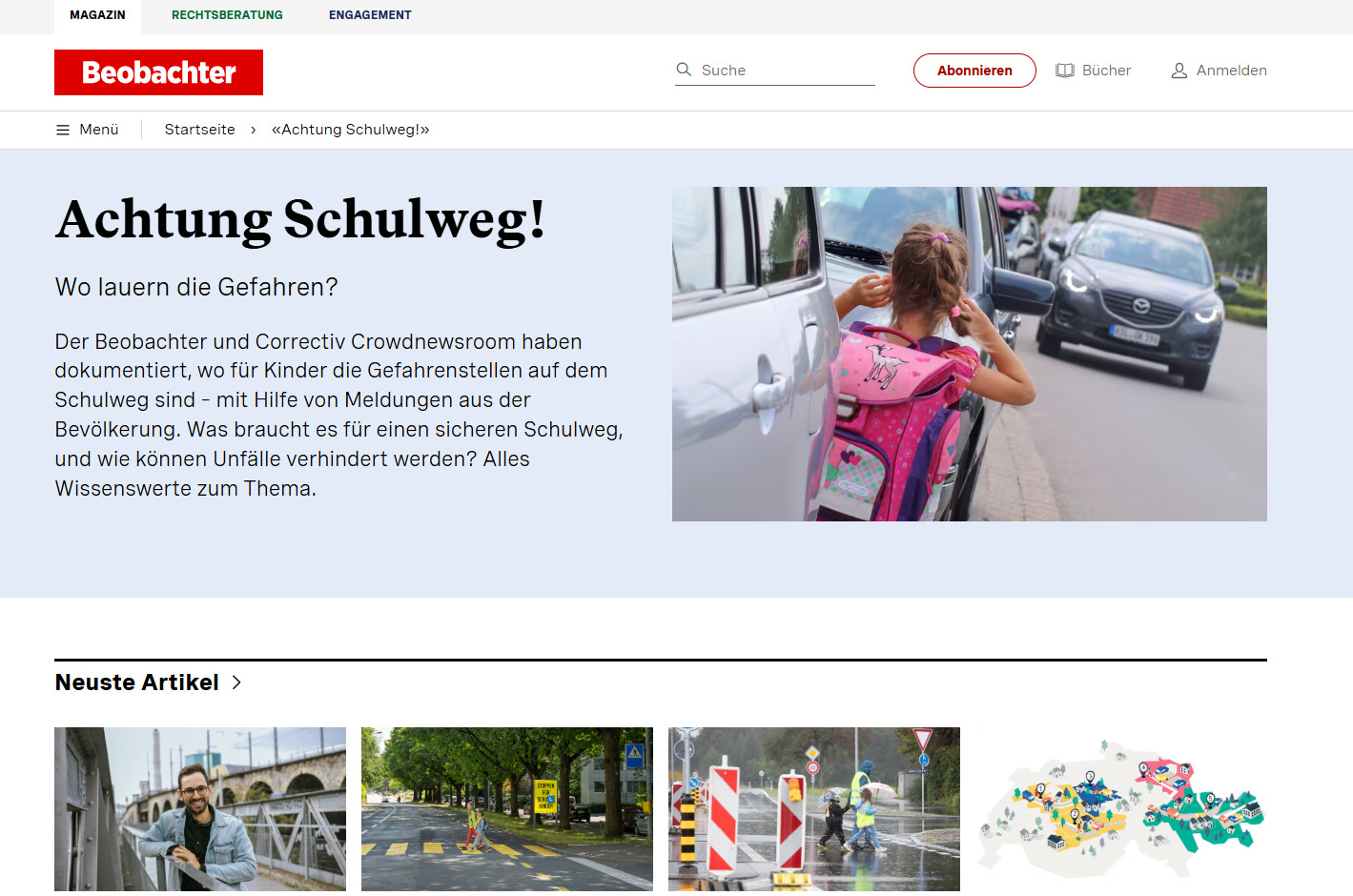

A similar investigation focused on the safety of routes to schools in Switzerland and Germany. Their latest project, Demolition Atlas Europe, is another strong example. The issue was flagged in 2023 by a local NGO in Switzerland. CORRECTIV’s reporters expanded it and brought it to a wider audience.

For more than a decade, CORRECTIV has been using CrowdNewsroom to share tools and data, supporting cross-border investigations and strengthening local reporting. It combines CORRECTIV’s open-source survey tool with paid access to coaching and resources for reporters conducting citizen-driven investigations. The stories generated from its use span a variety of topics, including domestic violence and the use of medications in professional football.

“Once you define your question, engaging people becomes easier,” said Marc Engelhardt, director of CORRECTIV’s CrowdNewsroom, to iMEdD. “Choose an issue that makes people angry — like high rents — and they will participate. Involve civil society to spread the word. (…) The story emerges from what people tell you, not what journalists decide in a meeting.”

The tool makes collaboration simple: team members can tag responses, leave notes for each other, assign tasks, and sort answers automatically.

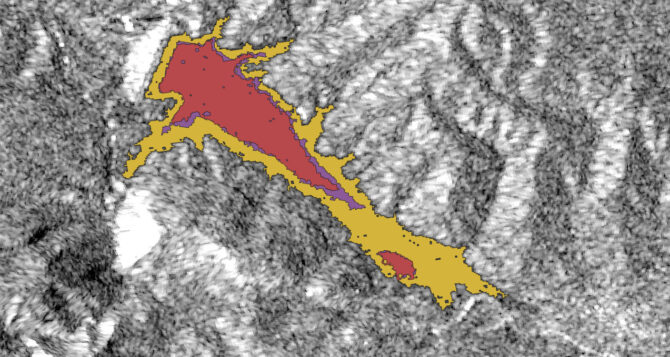

Two Satellite Images and QGIS are Enough to Find How Much a Lake has Shrunken

A guide for journalists on how to observe and measure the reduction of water reserves in water bodies, like the Aposelemi Dam in Crete, with the use and the analysis of satellite images.

“[CrowdNewsroom] is an investigation tool, like a form builder, but with more features that help process the answers. The most important part of it is the privacy, the sovereignty of the data, (…) the fact that you own the data,” said Will Franklin, Head of Engineering at CORRECTIV. “It is really your information, and you know that it is not going anywhere else.”

It comes at no cost if a newsroom has the technical capacity to run it. “Otherwise, there is a fee to cover hosting and support from our teams in Bern and Berlin, including updates, technical maintenance, and any workshops you might need,” said Marc Engelhardt. The fee typically ranges from hundreds to a few thousand euros, depending on the size and type of media organization.

Mapping Makoko: how drones, data, and residents brought a floating slum to light

Between 2016 and 2019, Jacopo Ottaviani, journalist, computer scientist, and senior strategist at Code for Africa, the continent’s largest network of civic tech and data journalism labs with teams in 21 countries, spent many months each year in Lagos.

Just minutes from Lagos’s gleaming skyscrapers lies Makoko, a sprawling floating slum of 200,000 to 300,000 residents living in precarious conditions. “When I opened Google Maps, I realized that there was no map of it. This was a little bit like a light bulb moment,” he said to iMEdD.

Luckily, there were already other mapping initiatives — Map Kibera and Humanitarian OpenStreetMap — that mapped underserved communities. In 2019, Code for Africa received a small grant and got the project started.

“For us, [mapping Makoko] was a tool for advocacy. We felt like the local population could use the map for their own interests. And we decided to release it as an open data map for the public to use. It’s also a way for people to assert their existence.”

Jacopo Ottaviani, journalist, computer scientist, and senior strategist at Code for Africa.

The preparation took several months. Code for Africa flew drones over Makoko to capture imagery, which residents mapped on OpenStreetMap. They also trained local women to fly the drones. Using the Open Data Kit app, the Makoko residents also mapped schools, clinics, and other points of interest, making the project truly crowdsourced.

The local data team at Code for Africa offered technical support to citizens using the Open Data Kit app and played a central role in crafting visual stories from the project’s findings. The data was then shared with the community to help people plan and advocate for improvements.

In 2021, the ‘Mapping Makoko’ project won a Sigma Award and, as part of a collaboration with the Pulitzer Center on Crisis Reporting, has been featured on several international media outlets, such as CNN Africa, Al Jazeera, France24, and the BBC.

“For us, it was a tool for advocacy,” said Ottaviani. “We felt like the local population could use the map for their own interests. And we decided to release it as an open data map for the public to use. It’s also a way for people to assert their existence. It’s a neglected community. Over the decades, they were consistently targeted by the authorities, who wanted to clear the area.”

Tracking Air Pollution Across Kenya

According to research by the State of Global Air Initiative, an international initiative on air pollution, several thousand premature deaths in the country are attributed to air pollution. Residents who are worried about the air they breathe are teaming up with engineers who built low-cost sensors, turning their concern into data that reveals hidden pollution.

The sensors were created by the engineers of Sensors.AFRICA, a pan-African citizen-science project launched in 2017. They are spread throughout selected cities across the continent. Each sensor measures microscopic airborne particles that can be harmful to health (PM2.5 and PM10), as well as temperature and humidity. The data feeds into an AI model that also incorporates satellite inputs from Sentinel-5P.

“This kind of data is very limited across the continent. It’s encouraging to have local engineers building these sensors, so we’re not entirely dependent on external sources,” said Alicia Olago, an environmental scientist, researcher, and senior program manager at Sensors.AFRICA. The unit is incubated into Code for Africa.

In fast-growing cities like Nakuru in Kenya, residents are now tracking the air they breathe with AI-powered sensors that monitor pollution across their neighborhoods in real time through the RESPIRA Air Quality Monitoring (RESPIRA-AQM) project. The initiative brings together scientists from Belgium’s KU Leuven, Kenya’s Egerton University, and a network of local and international partners.

“We do environmental monitoring,” said Olago. “The power of these sensors is that they let us see the whole picture. By using this Internet of Things (IoT) technology, we can gather real-time data and understand what’s really happening”.

The project is based on a bigger idea to improve access to data and strengthen journalism throughout the continent. Sensors.AFRICA, also employs sensors to track water, noise, and radiation pollution, providing residents with practical data about their cities.

The California Reporting Project: Mapping Police Misconduct

In California, an experiment in collaboration and crowdsourcing has reshaped how the public learns about police misconduct.

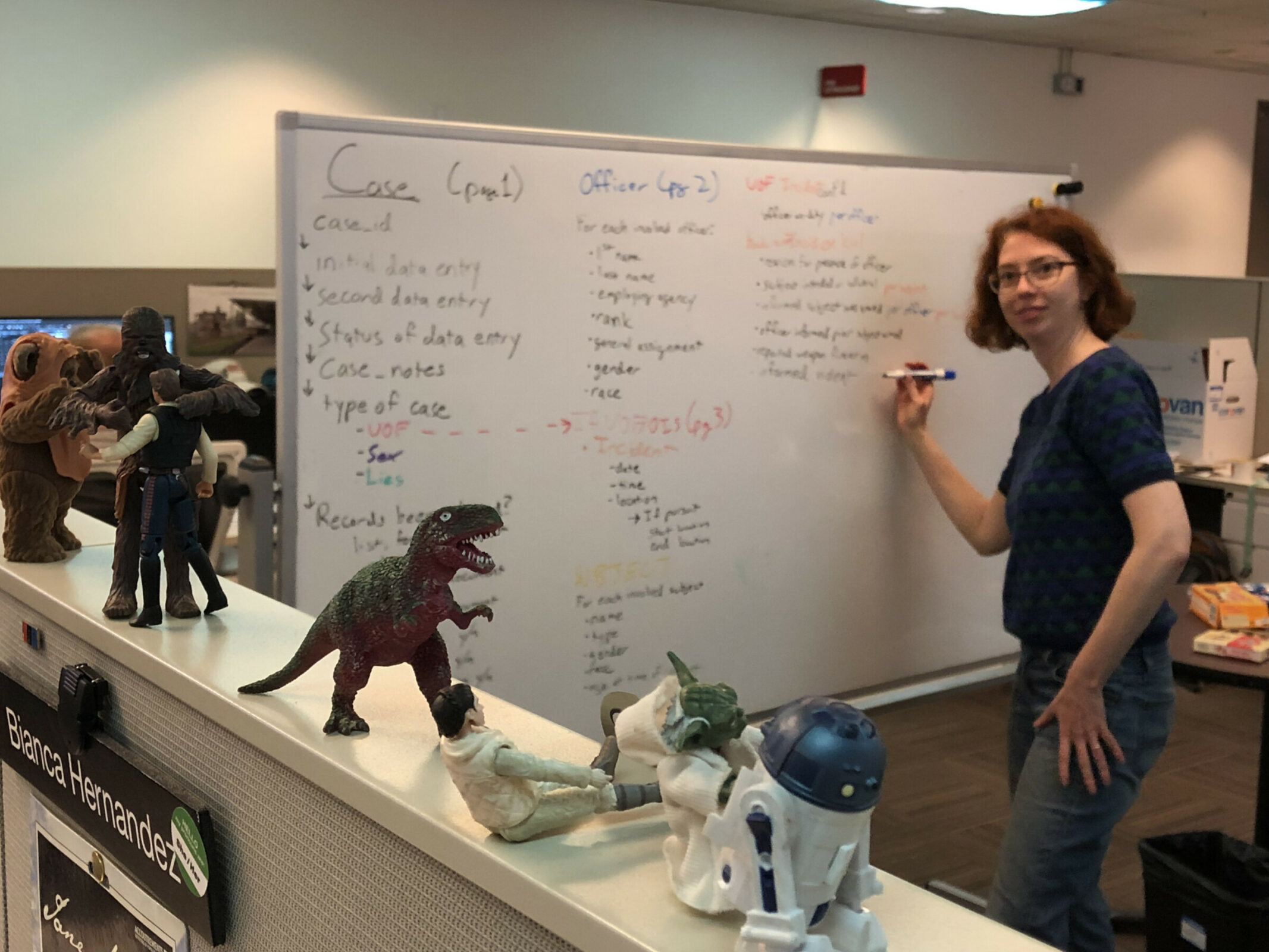

Over seven years, 115 journalists from 40 newsrooms and 50 students from two California universities, UC Berkeley and Stanford University, have worked on The California Reporting Project. The collaboration united newspapers, public radio, nonprofit newsrooms, and university programs. Since 2018, it has turned 1.5 million pages of once-secret police records from 2016 and 2024 on the use of force and misconduct into a free, searchable database.

It was a team effort from the start. “The six founding members grew to more than 30 within a month”, said Lisa Pickoff-White, the project’s research director and part of the project from the very beginning, speaking to iMEdD. The rapid growth reflected the enthusiasm of local reporters who had long talked about launching a project like this.

The idea took shape after the California Legislature passed SB1421, The Right to Know Act, which made records of investigations about the use of force, sexual assault, and official dishonesty public. Later, California’s SB16 law, effective January 1, 2022, broadened access to police records, adding cases of excessive force, failure to intervene, discrimination, and unlawful arrests or searches.

Pickoff-White said that with 700 law enforcement agencies in California, the sheer amount of data was overwhelming, and that’s why they decided to work together to tackle it thoroughly.

Turning chaos into a database

For years, journalists, students, and members of civic society and legal organizations volunteered their time on top of their regular schedules.

The journalists set up shared Docs and folders, worked on DocumentCloud, and built a custom database. Early attempts used Hugging Face – a platform for open-source machine learning models – to summarize text, but it struggled with police-specific language.

“Another big problem was that the files weren’t well organized when they arrived,” Pickoff-White said. “They were in all forms and shapes. We got hard drives, physical paper, video, CDs, and PDFs. Sometimes an agency would send five pages on one case and six pages on another.”

The team used Optical Character Recognition (OCR), a technology that converts scanned documents into machine-readable text, to extract data from incoming files, with humans reviewing and refining the information to ensure accuracy. The group then built AI tools to organize police files by case, grouping related reports like shootings, district attorney reports, and toxicology results. By 2024, they had developed algorithms to extract specific information from textual files.

Some of this data was published for public and journalistic use, while the rest supported further record requests, expanding the database, said Pickoff-White. They also classified documents and monitored redactions, correcting over-redacted files and removing sensitive personal information before publication.

Pickoff-White emphasizes that reporters and researchers must pair traditional reporting with the tool, not rely on it alone. “You can look up a name, and it will show you documents that contain it. We leave it up to the user to determine whether this is the person they think it is. We are not asserting that this is a specific officer or the subject of any incident of violence.”

The most impactful stories

The journalists published more than 100 articles from the files.

Early in the project, a criminal justice reporter, Sukey Lewis, reported a pivotal story, revealing that some police departments in California failed to investigate officer-involved deaths. The investigation found that 10% of 122 police agencies failed to investigate deaths caused by officers, pointing to gaps in accountability and officer training. “That had an impact, and there were changes in law after that,” said Pickoff-White. Following this, the “On Our Watch” podcast delved deeper into issues of police accountability and discipline.

“Additionally, I contributed to a story on prone restraint, published in collaboration with The Guardian,” Pickoff-White said. Her story followed Shayne Sutherland, who died in 2016 after officers held him face down for nearly nine minutes. High on meth but unarmed, he had called 911 from a convenience store for a ride, gasping for air and pleading for his life. His death foreshadowed the 2020 death of George Floyd, which shocked audiences worldwide. “His family ultimately received a $6 million settlement following his death,” she added.

At this year’s iMEdD International Journalism Forum, attendees will get a firsthand look at the Demolition Atlas Europe, a crowdsourced project that has documented more than 3,500 demolition sites across Europe with contributions from hundreds of citizens via the CrowdNewsroom platform.

Alicia Olago will lead a workshop demonstrating how drones, sensors, and satellite imagery are reshaping investigative reporting. Drawing on examples from Africa, she will show how technology has exposed pollution, influenced policy, and supported legal action, offering journalists practical tools to tackle issues ranging from climate change to social inequality.