The 20-ton cargo of polyester resin seized at the port and the “Lebanese Resistance Movement” in Beirut. What are “dual-use items,” and why do security gaps persist in European ports?

In the spring of 2024, a shipping container was seized at Piraeus’ third customs office. It contained unknown chemicals stored in plastic tanks – 20 tonnes in total – and according to the accompanying documents, the shipment was bound for Lebanon. Beyond the port authorities, the seizure triggered a major security response in Athens, as the case raised several red flags. An iMEdD investigation reveals that the final recipient was a company in Beirut linked to the Lebanese Resistance Movement, a minor political party that academics believe has ties to the political wing of Hezbollah.

The initial tip-off about the container came from the National Intelligence Service (EYP) in March last year. The first indication that this was no ordinary cargo was the contents of the tanks themselves. More specifically, analysis conducted at the General Chemical State Laboratory confirmed that the shipment was carrying a large quantity of polyester resin – a substance widely used as an insulating material, but also in the marine, aerospace, and defense industries.

According to the relevant EU Regulation, polyester resin is classified as a “dual-use-item,” a term referring to goods and technologies that have legitimate commercial applications but can also be exploited by authoritarian regimes or armed organisations for military production. The EU has imposed strict controls and prohibitions on the export of such materials from its member states.

Following the directive to detain the shipping container in March 2024, the EYP informed the relevant agency within the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, which handles license requests for “dual-use items,” as well as the Anti-Money Laundering Authority, according to correspondence between the involved agencies. The container’s departure was prohibited, and the cargo remained detained at the port.

Syrian Shipowner in Piraeus on Sanctions List

A Houthi-linked exchange house, oil for Hezbollah, and two merchant ships at the centre of an international legal battle.

From China to Lebanon

Meanwhile, a separate investigation has been launched into the shippers and recipients of the cargo. According to the accompanying documents, a large company in Shanghai, China, specialising in the production of unsaturated polyester resin and other chemicals, is listed as the shipper of the chemicals. The company did not respond to written queries regarding the container and its final consignee. As for the recipient, initial information pointed to a company in Beirut that, according to investigators, was not involved in the case.

The available information, however, led Greek authorities to a second importing company in the Al-Mazraa area of Beirut. According to Lebanon’s company registry, the sole shareholder of this company is a man identified by the initials J.D. A representative of a Lebanese logistics company, whom iMEdD spoke to at J.D.’s suggestion, stated that arrangements were being made for the cargo’s release in Piraeus. She added that this was not the first time the Beirut-based company had imported polyester resin, which “would be made available to the construction industry.” She also claimed that the company’s owner is J.D.’s brother, whose name does not appear in the company register.

J.D. is both a political figure and a philanthropist. Among other roles, he heads a charitable foundation in Beirut. In the fall of 2024, amid the war with Israel, he used his Facebook page to issue appeals for collecting essential supplies for refugees and displaced persons. iMEdD’s investigation also reveals that J.D. is the leader of the “Lebanese Resistance Movement”. This is a relatively unknown political party, which seems to have little appeal in Lebanon.

In February 2024, J.D. appeared as a guest on a TV show on Al-Manar TV, Hezbollah’s official channel, speaking in his capacity as the head of the Lebanese Resistance Movement. He has also been featured in several news reports on the organisation’s website. A Beirut-based academic with knowledge of Lebanon’s political landscape told iMEdD that J.D. is Sunni and speculated that Hezbollah’s media—traditionally Shiite—may be promoting him to demonstrate that the organisation has a presence among a broader segment of the population.

A second source in Beirut pointed out that, especially at that time, only individuals with close ties to the organisation would have been invited as guests on the Hezbollah channel. J.D. did not respond to iMEdD’s written inquiries by the time of publication.

The explosion in Beirut

Hezbollah is a Shiite political party that participates in the Lebanese government and parliament. Its armed wing is considered a resistance movement in the Arab world, while western countries, the European Union, Israel and Gulf Arab states classify it as a terrorist organisation.

U.S. judicial authorities have stated that many charitable foundations act as a support network for Hezbollah, allegedly funding the group through campaigns, fundraising efforts and paid media advertisements. The charity in Beirut controlled by J.D., however, is not mentioned in the U.S. documents.

In August 2020, the organisation was accused of being linked to the massive explosion that devastated Beirut’s port and parts of the Lebanese capital. The explosion killed more than 200 people, injured thousands and left a significant portion of the city’s population homeless. It was reportedly caused by a fire in the port’s warehouses, allegedly controlled by Hezbollah, where a large consignment of ammonium nitrate had been stored for years without security measures. Hezbollah denied the accusations, but opposed any investigation into the explosion’s cause.

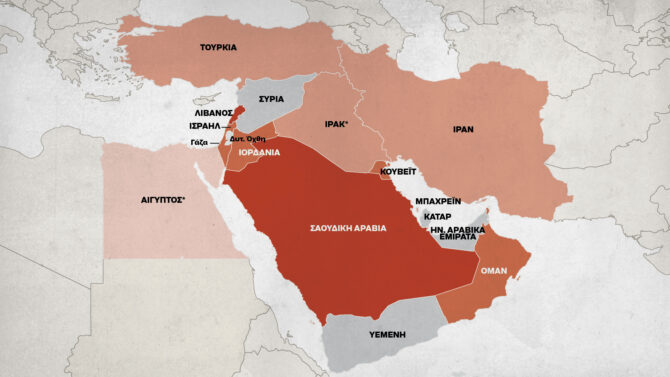

Military Expenditure in the Middle East: Who spends more?

Turkey and Israel increased their military expenditure more in 2023 than in 2022. A large percentage of GDP is spent on military expenditure for the economically struggling Lebanon.

Titanium rods

Back at the port of Piraeus, in late November, an order was given to destroy the chemicals intended for transport to Lebanon. According to reliable sources, to avoid the Greek state bearing the costs, there is ongoing correspondence with the shipping company that handled the shipping container to arrange for the destruction of the 20 tonnes of polyester resin.

In the past 15 months – since the Hamas attack on Israel on October 7, 2023 – Greek authorities have handled at least four similar cases, a source at the port of Piraeus reveals. “In the previous period, the incidents were even more frequent,” the source said, without providing any further details.

According to a European Commission report, in 2022 (the latest available data) member states authorised €57.3 billion worth of dual-use exports, representing 2% of non-EU goods exports. In 831 cases, exports worth €0.98 billion were blocked due to security risks. EU controls on dual-use item exports reduce trade friction with third countries and safeguard international peace and security.

In spring 2023, two containers carrying titanium rods were seized in Piraeus. The cargo had originated in Shanghai and was bound for Istanbul, with a stopover in Piraeus. Titanium falls under dual-use legislation due to its application in the defense industry, owing to its strength-to-weight ratio, corrosion resistance, and thermal stability. The initial tip-off about the cargo in Piraeus allegedly came from a foreign agency to the Anti-Money Laundering Authority in Athens.

In addition to titanium, the shipping containers also carried a lathe and various chemicals. Army bomb disposal experts, equipped with specialized gear for handling radiological and nuclear threats, inspected the cargo. Although the official destination of the titanium rods was Turkey, relevant security services suspect that the cargo was destined for Iran.

The security gaps in European ports

Anna Sergi, Professor of Criminology at the University of Essex specialising in organised crime and mafia mobility, has studied security gaps in major European ports. “The most common way to transport illegal goods is by using legal documents to ship them. All you need to know is which ship the container will be loaded onto, then simply falsify the documents. Corruption at the port is not even necessary – it’s typically done through fake companies,” Sergi told iMEdD.

When asked about the container seized in Piraeus, which she was not familiar with, Sergi commented, “I suspect that in this case, it was the destination country that sounded the alarm first. It’s good that the Greek authorities were able to check the cargo. Normally, outgoing cargo is not checked,” she said. “It is very difficult for large ports in Europe to inspect goods leaving the Union. So this is an interesting case, but it’s not the norm.”

Nicholas Marsh, a senior researcher at the Peace Research Institute (PRIO) in Oslo, specialising in arms trafficking, told iMEdD that the likelihood of accidental screening to intercept unlicensed dual-use items is very low.

“It’s not a weapon you can detect. With chemicals, if a false declaration is submitted about the type of cargo, it becomes even harder for customs officers to identify it, unless the shipper is just plain stupid,” Marsh said. “Enforcing trade regulations for dual-use items is very difficult without intelligence-driven investigations.”

Translation: Anatoli Stavroulopoulou.

Read all articles and analyses of the Special Report: “Armories of the Middle East” here.

This article was first published on Feb. 22 by the weekend edition of the newspaper “TA NEA”.