Even as politics shift, the struggle to report the truth continues, both inside Venezuela and from abroad. After the ousting of Nicolás Maduro in January, iMEdD talked to a media expert, two editorial cartoonists, and an investigative journalist in exile for years. We asked what has changed. Their answer was stark: very little.

Images: Courtesy of Rayma Suprani and Camila de la Fuente

Featured image: Cartoons by Rayma Suprani. Courtesy of Rayma Suprani.

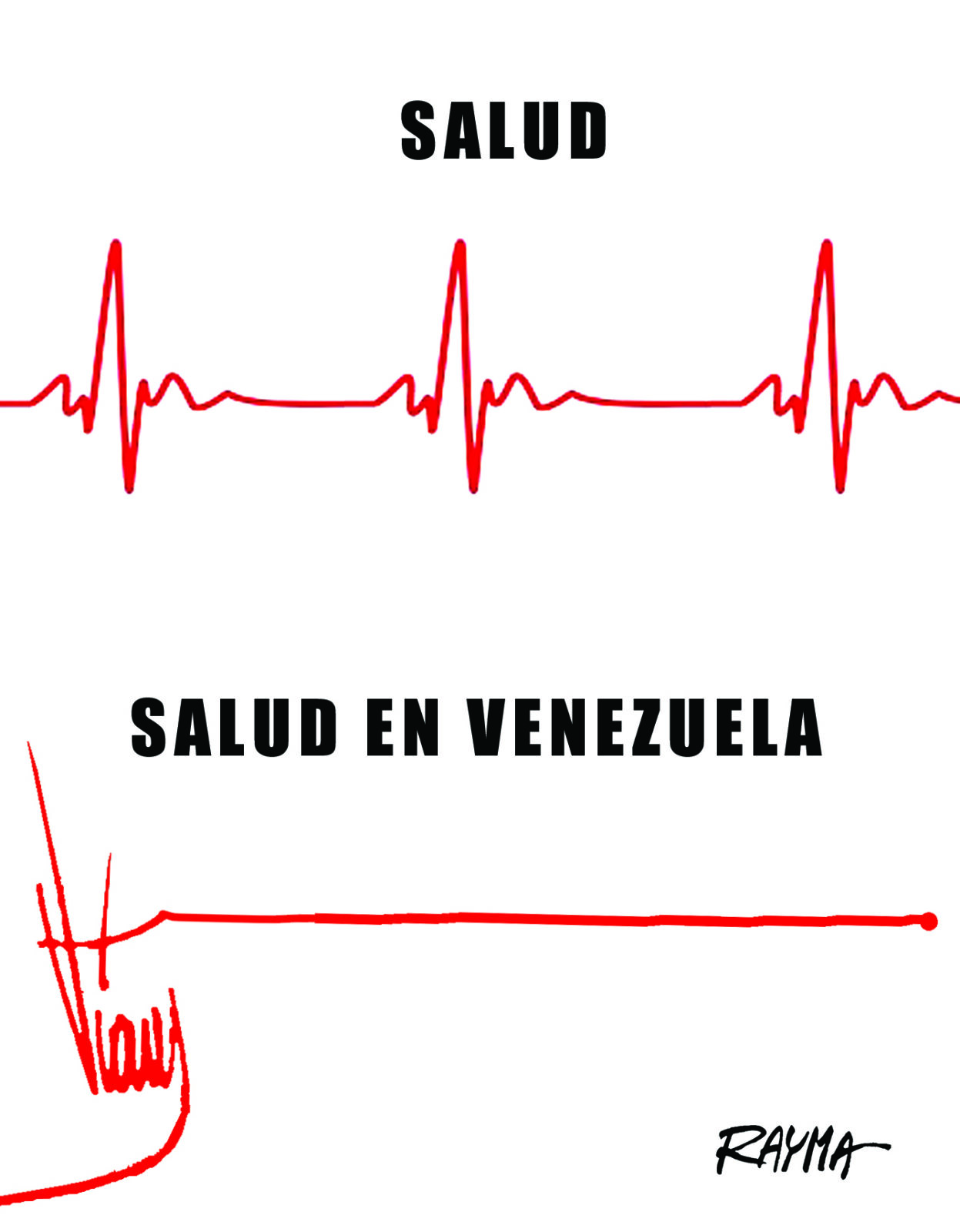

Censorship, internet blackouts, and the constant threat of harassment have continued to shape what Venezuelans can read, watch, or publish for decades. For one of the country’s best‑known cartoonists, Rayma Suprani, that reality hit home in 2014, early in Nicolás Maduro’s presidency.

It was a single editorial cartoon that cost her job at El Universal, a conservative 105-year-old daily newspaper, where Suprani had been one of its most recognizable cartoonists for 19 years.

She had turned the late Hugo Chávez’s signature, the Venezuelan president who ruled from 1999 until he died in 2013, into a flatlined electrocardiogram. Beside it, she drew another pulse that kept beating. The message was not subtle. In Venezuela, the hospitals were dead, stripped bare by a system that had run out of gauze, medicine, and excuses.

“They called me to a meeting to ask me to self-censor, which I refused to do, and I continued working in my graphic style of free thinking,” she told iMEdD.

The cartoon was published and accelerated her departure to the United States.

The editor who fired her told her that the cartoon “has been very upsetting”. “I was glad to see that the cartoon had an effect on the totalitarian system and that the complaint had been effectively lodged, even though I knew that losing my job in a country where the media is silenced was a frightening prospect for me,” she said.

The erosion of Venezuela’s free press

Suprani left soon after her dismissal and now lives in Miami, running her own studio. In the months leading up to her departure, the threats had grown impossible to ignore: legal notices arrived, anonymous calls on her cellphone filled with insults came day and night, and her cartoons, alongside her photograph, were broadcasted on state television as proof of her so-called “treason”.

Her experience was not an isolated case, but part of a broader effort to bring Venezuela’s media to heel.

After the Chávez era, Venezuelan media came under relentless pressure to toe the government line, she explained. “Restrictions on advertising, limits on paper for printing, the denial of radio concessions, and direct threats created a climate of fear that suffocated independent journalism.”

There is a playbook that is followed by authoritarian leaders, leftists or rightists, around the globe, as we can see now in the US. (…) It was very clear that the [Maduro] government had a very low level of criticism against them.

Cristina Zahar, Latin America program coordinator, the Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ)

The media ecosystem, as she knew it 20 years ago, no longer exists and is censored.

Over the past decade, a wave of journalist imprisonments has made Venezuela the country with the most reporters behind bars in the Americas, according to data from the Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ).

In Venezuela, “there is a playbook that is followed by authoritarian leaders, leftists or rightists, around the globe, as we can see now in the US. (…) It was very clear that the [Maduro] government had a very low level of criticism against them,” said Cristina Zahar, CPJ’s Latin America program coordinator.

That playbook tightened further after the 2024 elections. In the months that followed, independent news organizations and NGOs inside and outside the country described another sharp escalation in government pressure on the press, as former president Nicolás Maduro’s administration moved to further silence critical coverage through arrests, legal threats, and the closure of media outlets.

News radio stations were now converted into all-music ones, well-known journalists were removed from the air, and CONATEL, Venezuela’s state telecommunications regulator, ordered both public and private internet providers to block access to several independent and fact-checking news outlets.

For investigative journalist Ronna Rísqez, the choice to flee increasingly mirrored Suprani’s. Rísquez, the coordinator of Alianza Rebelde Investiga, now based abroad in a location she prefers not to disclose, left Venezuela a few months after the presidential elections in 2024. “I needed to feel safer,” she told iMEdD. “So, I thought I’d leave for a couple of months, but the repression only got worse.”

Rísquez also noted that Venezuelan news outlets have been chronically underfunded. “They cannot pay journalists decent wages, and since 2024, their payrolls have been reduced by more than half.”

Still, independent journalism has not disappeared. Ιt has adapted.

Several independent investigative media, however, such as Efecto Cocuyo, El Pitazo, Runrunes, TalCual, and Caracas Chronicles, have persisted in publishing. Locked out of much of the domestic web, these sites have become, in Rayma Suprani’s words, “a platform for free thought and creative resistance” for Venezuelans at home and nearly eight million in diaspora.

Access denied

After Maduro’s capture by the US, conditions remain unchanged, said Rísquez. “Digital media remains blocked, and journalists are not allowed access to government activities or interviews with government officials.”

On Jan. 5, as Delcy Rodríguez was sworn in as interim president of Venezuela, at least 14 journalists and media workers were briefly detained by security forces while covering the inauguration, according to the National Union of Press Workers of Venezuela (SNTP).

Authorities have also continued to restrict access for international correspondents, said CPJ’s Cristina Zahar. Reporters Without Borders (RSF) reported that roughly 200 international journalists have been stranded in Cúcuta, Colombia, unable to enter Venezuela. “The ones who can enter must have Venezuelan papers”, she added. Meanwhile, Venezuelan photographers who do manage to enter are sometimes intimidated at airports, with their equipment temporarily seized before being returned after several hours.

Rísquez noted only a few modest signs of progress. Nineteen journalists jailed for their work have been released at the end of 2025, and in early February Rory Branker, journalist of La Patilla, who had remained behind bars since early 2025 was also freed.

At the end of January, Delcy Rodríguez, announced plans for an amnesty bill that could result in the release of hundreds of prisoners, including opposition leaders, journalists, and human rights activists imprisoned for political reasons.

“This can be good and bad at the same time,” said Zahar, “because if this law passes, all the journalists and activists who are currently jailed can be released and the charges can be dropped.” At the same time, all Maduro supporters, militias, and government backers could be cleared of all charges under the law.

But even if journalists are released, Zahar explains that the charges remain, because of the amendments to the Penal Code that added Article 297-A establishing prison sentences of up to five years for anyone who “divulges, in any medium, false information that causes panic.” “What journalists want is a full pardon,” she adds.

For me, translating all these years of the dismantling of the republic and being a graphic translator of the feelings of Venezuelans in this time of struggle and resistance has been very important work.

Rayma Suprani, Venezuelan cartoonist and journalist

Reaching audiences at home and abroad

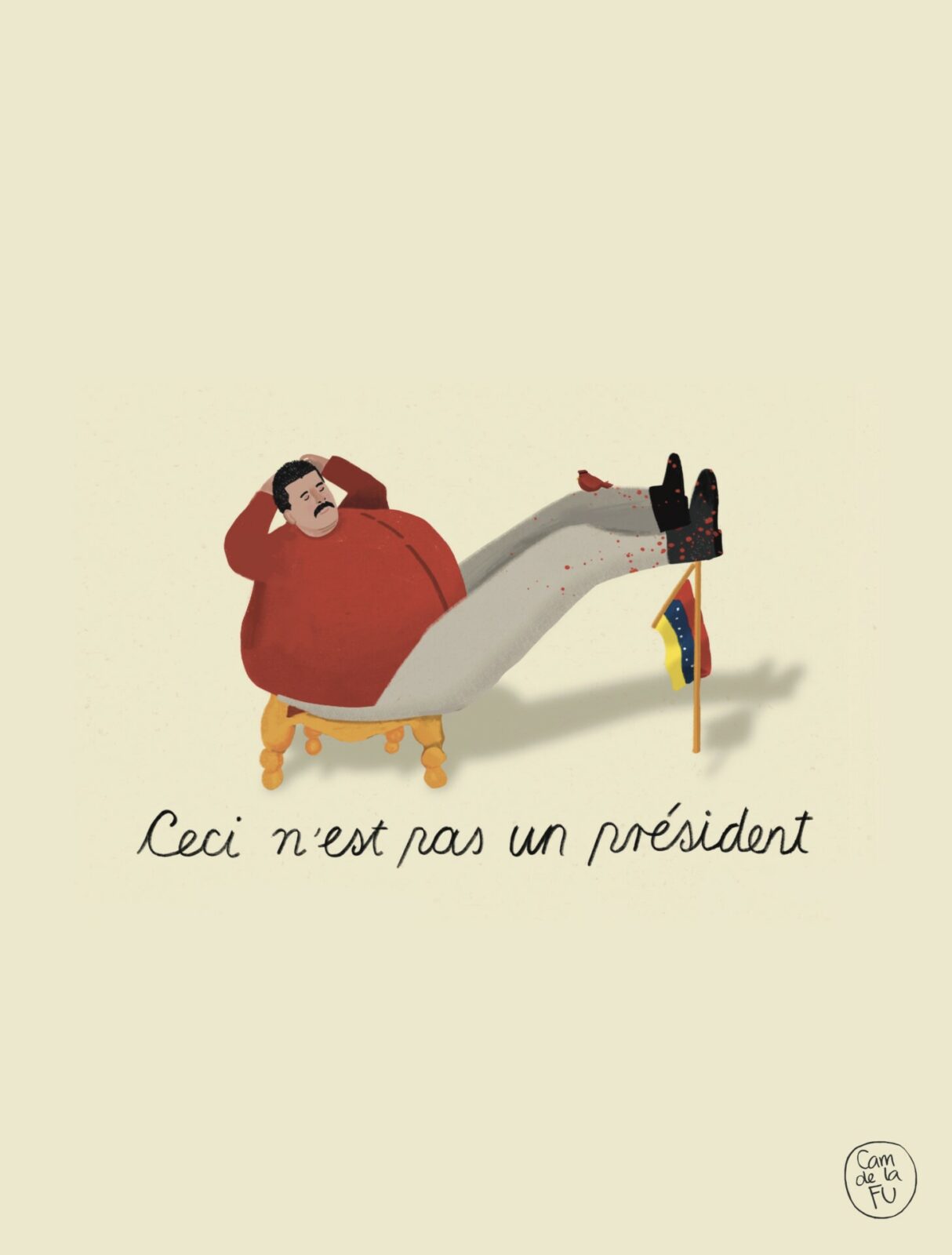

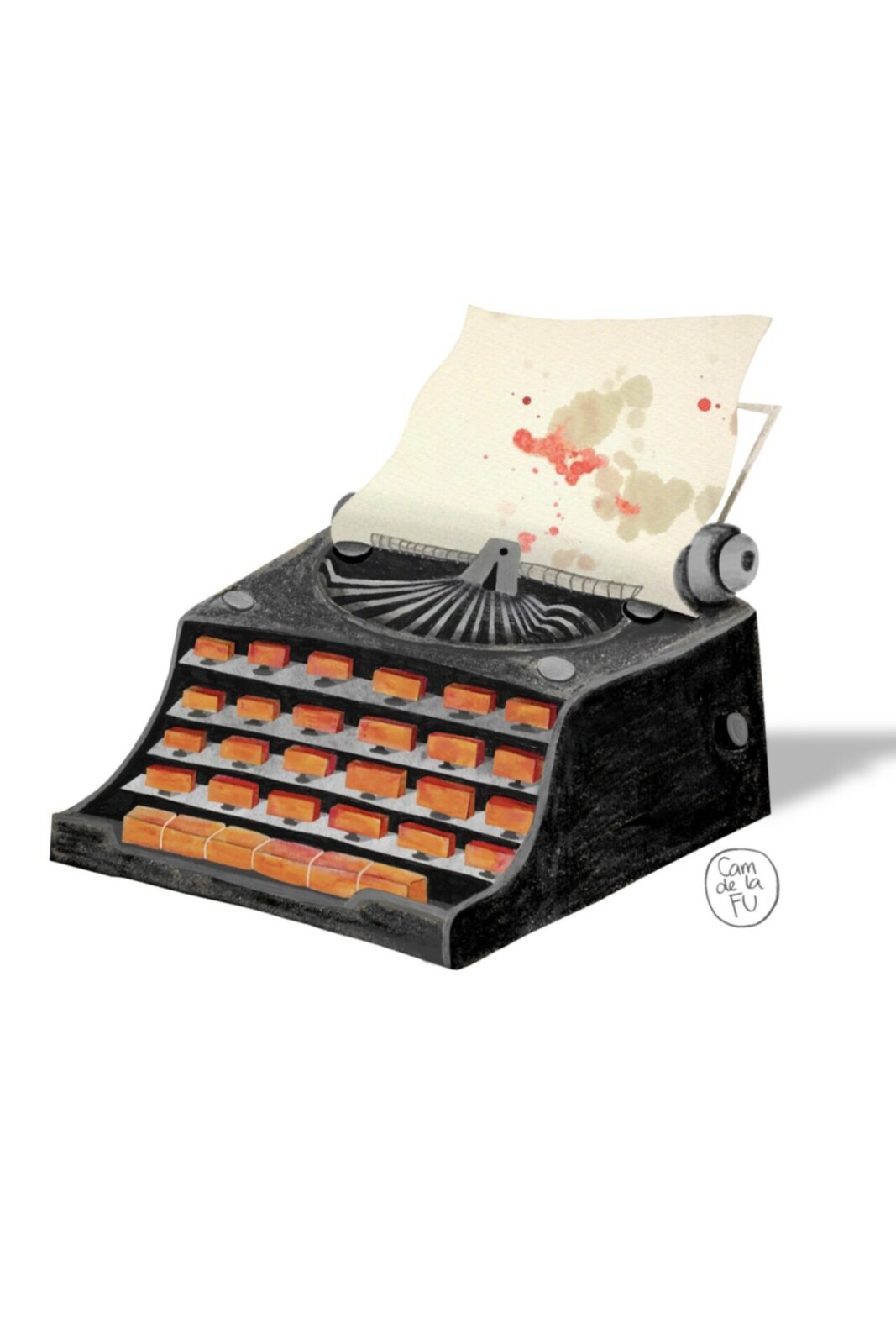

Camila De La Fuente, a freelance Venezuelan-Mexican journalist, cartoonist, and illustrator, has used her work to document life under authoritarianism in Venezuela and to draw attention to human rights abuses, power consolidation, and forced migration. Although she fled the country with her family in 2014, her work continues to resonate with audiences inside Venezuela and across the diaspora.

In January 2025, she donated one of her works, Elections Under Dictatorship, to the Organization of American States Museum in Washington. The piece, now part of the museum’s exhibitions, reflects what she described at the ceremony as a deeply personal motivation. “I fight so that my daughter never has to go through what I went through in my life, so that her freedom is never taken away in any country where she decides to live.”

Inspired by her parents’ activism, she became involved in student protests in 2012. “We were protesting because the insecurity and the inflation were crazy,” she told iMEdD.

The police were checking cellphones. She always carried two, “one in case the other was stolen”. She still recalls the media blackouts and arbitrary detentions during the protests. “I specifically remember that all the media had to show the President when he spoke. And it was right when the police were about to shoot [the protesters],” she added.

Reflecting on the political landscape, she said, “I’ve been amazed to see how the dictatorship preferred to bow to the U.S. rather than admit that they lost the elections,” underscoring the regime’s reluctance to acknowledge electoral outcomes. At the same time, she expressed hope that the new government will uphold journalism and human rights.

“At this moment, there is no freedom of the press in Venezuela,” said Rayma Suprani, mentioning that earlier in February, Venevisión, one of Venezuela’s largest television networks, managed to broadcast a report on statements by María Corina Machado, only for Diosdado Cabello to appear on his program shortly afterward, directing threats at the channel.

To continue producing her cartoons on current events in Venezuela from afar, she consumes a lot of information, even from a “clandestine network” of citizens that has been created over the years, broadcasting current events in real time, always filtering out the fake news.

“For me, translating all these years of the dismantling of the republic and being a graphic translator of the feelings of Venezuelans in this time of struggle and resistance has been very important work,” she said. “Because I know that these drawings accompany history over time (…) Being a Venezuelan journalist and cartoonist has given me the opportunity to develop a personal style where I have the honor of being the voice of those who have no voice or are threatened, and that is a great responsibility.”

At the same time, journalists warn of growing audience fatigue within Venezuela. Rísquez said that audiences in Venezuela are often overwhelmed by information, particularly a steady stream of bad news, and that many people choose to tune it out.

Yet, the demand for trustworthy journalism is still there, though alternative platforms, such as WhatsApp, or relying on a VPN, among others.

“People have a great need to receive quality information — reliable, verified, and timely information,” she said. She pointed to a live broadcast she helped organize on Jan. 3, an 11-hour uninterrupted stream that drew thousands of YouTube viewers eager for on-the-ground reporting.

The lack of information and recurring digital shutdowns have forced Venezuelans to rely on digital tools to bypass restrictions. Independent journalism, argued Risquez, must do the same.

“I think that, as always, investigative journalism has to adapt to today’s reality, explore, and not discard different ways of reaching audiences,” she added. “It should use the tools that are available, such as AI, and form alliances with influencers and YouTubers.”

CPJ’s Emergency Response Team (ERT) provides one-on-one consultations and workshops on digital and physical safety for journalists. The organization also offers short-term financial aid to displaced or newly exiled journalists, helping cover basic living costs and profession-related health, legal or psychological needs, but it does not support long-term operations for exiled media outlets. Contact them for assistance at [email protected].

This article is published by iMEdD and is made available under a Creative Commons license (CC BY-NC 4.0). This license does not apply to the images by Rayma Suprani and Camila De La Fuente included in this publication, which are published courtesy of the creators for the purposes of this piece. Any other use of these images by third parties requires prior communication with the creators for their permission.