How is U.S. energy and climate policy looking under a second Trump administration, and what should we expect from this year’s United Nations Climate Change Conference (COP29) already underway? iMEdD spoke with energy and climate policy experts, Andrea Clabough and Bob Ward, seeking answers.

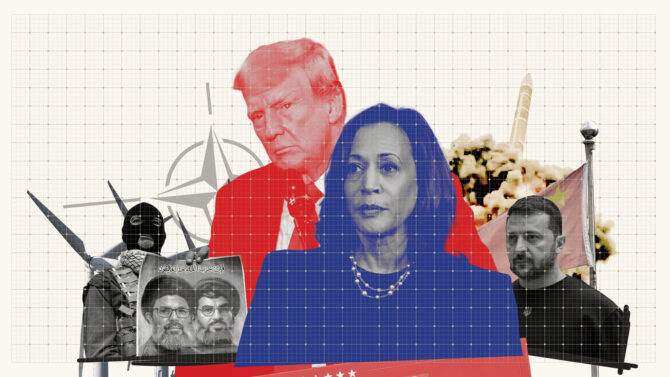

US Elections: Two Scenarios for Five Crises

How the outcome of the US elections will will have significant implications for five major international crises, according to analysts speaking to iMEdD just days before November 5.

Five days after Trump’s election, COP29 kicked off in Azerbaijan’s capital, Baku. While this COP’s aim is to mobilize financing from richer to low-income countries to accelerate the transformation of their energy sectors, experts remain skeptical of a possible breakthrough. “We will have to see whether there is a deal,” said Bob Ward, Policy and Communications Director at Imperial College’s Grantham Research Institute on Climate Change and the Environment, speaking to iMEdD from Baku.

On the edge of the Caspian Sea, the tides of hope and urgency meet. “If poorer countries do not receive financial support from the rich countries to transition away from fossil fuels, it is going to be very difficult for them to come forward with more ambitious climate pledges,” stressed Ward.

The Diplomatic Wrestling of COP29

The financial objective of COP29 is extremely ambitious. The 2009 goal to raise 100 billion $ for the climate was only met in 2022. The sum now deemed necessary by scientists to curb climate change is close to 1 trillion $ per year, which – even experts admit – sounds unrealistic. Andrea Clabough, non-resident fellow at the Atlantic Council’s Global Energy Center, shared with iMEdD, from Washington, that climate finance is not a priority for the Trump administration, especially given the tax negotiations, that will begin in Congress this spring, which will, among others, touch on green energy. “The outlook is bit dark; we need to galvanize other large emitters, like India, China and the European Union, around shared climate goals,” she explained.

It does not help either that COP29 precedes the 10-year anniversary of the Paris Agreement, whereby all 193 UN Member States will have to submit their updated emissions-reduction commitments “to curb global warming below 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels.” The incoming U.S. President, Donald Trump, notoriously withdrew the U.S. from the Paris Agreement in 2017, a decision later overturned by the Biden administration. Delegates in Azerbaijan watch as the U.S. turns a familiar page, raising questions that span borders and soon generations. Should Trump decide to withdraw once more, how will the other large emitters react? Ward does not think leaving the Paris Agreement will be “a fatal blow” for negotiations though. “China is the largest emitting country but also by far the biggest investor in electric vehicles and renewable technology. I would not expect China to weaken its commitments to Paris just because Donald Trump has,” he added.

Trump’s potential withdrawal from international agreements, however, raises concerns about energy security, particularly vis-à-vis the two ongoing conflicts in Ukraine and Gaza. The Biden administration managed to come out smoothly from the Russian invasion of Ukraine by preventing a long-enduring price spike and becoming Europe’s biggest supplier. In 2024, Europe alone accounted for 49% of all U.S. LNG (liquified natural gas) and 47% of all U.S. crude oil exports. In the Middle East, however, an expansion of Israel’s war in Gaza would undoubtedly impact the wider region and by extent international markets.

China is the largest emitting country but also by far the biggest investor in electric vehicles and renewable technology. I would not expect China to weaken its commitments to Paris just because Donald Trump has.

Bob Ward, Policy and Communications Director at Imperial College’s Grantham Research Institute on Climate Change and the Environment

According to Clabough, “the Trump administration will attempt to pursue maximum pressure against actors like Iran,” including imposing strict sanctions on the OPEC member’s oil industry, “in order to bring the country back to the negotiating table.” Given the energy insecurity brewing in the Middle East, Ward believes that fossil-fuel-dependent countries need to ultimately develop domestic energy alternatives, including nuclear; a scenario that recently made headlines during the Italian Prime Minister’s speech in Baku. “We need a balanced energy mix,” said Georgia Meloni, “not only renewables, but also gas, biofuels, hydrogen, CO2 capture and, in the future, nuclear fusion.”

US-China: The day after and the U.S. elections in Nov. 5

iMEdD spoke with Columbia University Political Science Professor Andrew Nathan about Democratic and Republican attitudes toward Beijing and US-China relations in the wake of the US elections.

Heads also turned when even the host country’s President, Ilham Aliyev, doubled down on fossil fuel production and called oil and gas a “gift from God.” Oil and gas make up more than 90% of Azerbaijan’s exports, with state-owned monopolies, such as the SOCAR oil company dominating the industry, despite Baku denying the title “petrostate.” To make the situation stickier, Azerbaijan’s “green” energy projects are concentrated in Nagorno Karabakh, a disputed region from which Armenians were forcedly displaced in 2023, further weaving the complex web of conflict and climate policy. Compounding this tension, Azerbaijan – now the third consecutive COP host accused of oppression – has drawn criticism for its record of over 300 political prisoners, including journalists, climate activists, and regime opponents.

In a city born of oil but dreaming of sustainability, every conversation feels weightier and every promise more profound. However, the adversity of climate diplomacy cannot be denied, especially when COP29 has granted access to 480 lobbyists for carbon capture and storage, an ineffective substitute to the very urgent need for decarbonization. Nevertheless, Ward recognizes the progress made, despite the fractured diplomatic landscape. The need to transition away from fossil fuels was explicitly called for during last year’s COP in Dubai; “we wouldn’t have been able to get that language if the host itself wasn’t a major producer,” said Ward.

What to Expect From Trump’s Energy Policies

As the climate crisis takes center stage in Baku, it is uncertain whether the policies of a reshaped U.S. administration could stoke the coals of global climate collaboration. From changing the administration of the Clean Air Act, a comprehensive federal law that regulates air emissions since 1970, to approving major projects like the extension of the Keystone petroleum Pipeline in 2017, Donald Trump holds the record of overturning more than 100 environmental rules, setting the country back decades. “We’ve already seen how the Trump administration approached energy; they had this mantra of energy dominance, and I think that gives us helpful clues as to where they’re going next,” said Clabough.

What Republicans will try to do is, instead of taking a hammer to the environmental laws, go for a scalpel, and attempt to carve out areas that are less favorable.

Andrea Clabough, non-resident fellow at the Atlantic Council’s Global Energy Center

Clabough explains that we are possibly looking at another massive overhaul of the U.S. regulatory and legislative slate. The Trump administration is most likely going to rescind elements of high-profile bills like the 2022 Inflation Reduction Act (IRA), the country’s single largest investment of 369 billion $ in the climate and “green” consumer incentives. The controversial “Project 2025” will also impact the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). Clabough speculates that, among others, the EPA’s Power Plant Rule, which aims to reduce pollution by fossil-fuel-fired power plants, could be affected by Trump’s regulatory crusade.

Despite a Republican Congress, Clabough said that “repealing laws like the IRA is going to ruffle some feathers and could result in litigation, because we’re seeing so much money going into red and purple states as a direct result of these laws.” Even hardcore red states like Texas have benefitted from the diversification of their clean energy portfolios. Investment in Texas’ solar, onshore wind, and, now growing hydrogen and carbon capture industries, is estimated at over 83.2 billion $, generating millions of tax dollars and boosting the labor market. “What Republicans will try to do is, instead of taking a hammer to the laws, go for a scalpel, and attempt to carve out areas that are less favorable,” concluded Clabough.

Columbia Journalism Review: Trump Wins, the Press Loses

A second Trump administration is poised to be devastating to journalism.

Looking Ahead

Amid Baku’s fervent discussions, the shadow of Washington looms, reminding us of the intricate web of global interdependence. During Donald Trump’s second term, greenhouse gas emissions are predicted to increase by 2.7 billion tons by 2030.

On an even gloomier note, UNEP’s 2024 Emissions Gap Report showed that not only have we not managed to limit the global temperature increase to 1.5 °C, but that we are even looking at an increase of 2.6 – 3.1 °C by 2100.

Ward explained that “we haven’t had temperatures 3 °C warmer than pre-industrial, on Earth, for three million years,” a phenomenon experienced during the Pliocene epoch, when global sea level was 5-25 meters higher than today. “Modern humans have only been around for 250,000 years, so anybody who thinks we can just adapt to this, really doesn’t know what they’re talking about,” he exclaimed.

As delegates convene under the Azeri sky, it becomes critical that they come forward with blueprints for an even “greener” tomorrow, especially ahead of COP30 in Belém, Brazil. Unless the big emitters set their interests aside, global climate cooperation will be once more pushed to the sidelines. This time, experts say, to the point of no return.