As 2023 came to an end, we witnessed the unfolding of COP 28, the world’s biggest international climate summit. Yet, the spotlight belonged to the Israel-Palestine conflict’s heavy humanitarian toll and its huge impact on water and land. At the same time, a global fossil fuel “race to the bottom” took the world by storm. Political Analyst and Middle East expert, Adrián Mac Liman, and Professor and Senior Research Scholar at Columbia University’s Center on Global Energy Policy, Dr. Harry Verhoeven, share their insights on the nuances of environmental policymaking, the diplomatic relevance of another conflict in the Middle East and their predictions on the future energy order.

Where and how journalists are being killed in Gaza

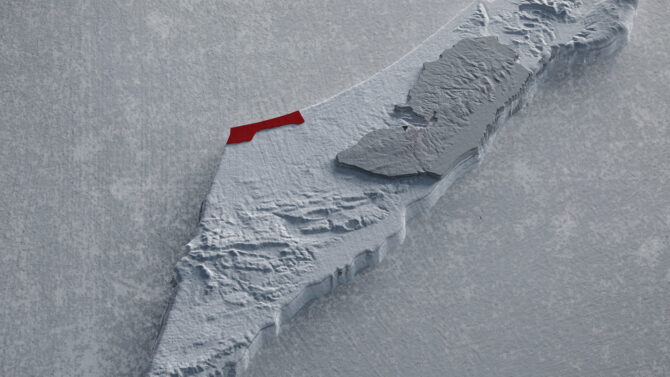

An interactive map of where and how journalists and media workers were killed in the Gaza war, according to CPJ data.

The Conference of Parties (COP) is the supreme decision-making body of the United Nations Framework Convention for Climate Change (UNFCCC). Spanning from November 30th to December 12th, 2023, COP 28 was hosted in Dubai, UAE, with representatives from almost 200 nations. Over 130 countries forged a consensus to prioritize food security and agricultural emissions cuts, while over 110 countries pledged to double energy efficiency by 2030. Most importantly, UN Secretary-General António Guterres adopted a text on a complete fossil-fuel phase out, for the first time in COP history, with a view to reaching net-zero by 2050.

However, the key paradox of this year’s COP lay in its references to sustainability. Having now surpassed the 100-day milestone of the war in Gaza, bomb attacks have led to the death of nearly 24,000 Palestinians, polluted water, and soil, and destroyed critical ecosystems 2,500 km from the summit. At the same time, while the energy status quo is still uncertain in the face of the continued war in Ukraine, fossil fuel lobbying even took place on the sidelines of the conference; developments that raise questions about whether COP 28 could ensure sustainability altogether.

The Israel-Hamas war highlights the power (and the limits) of open-source reporting

The use of OSINT to report accurately on the Israel-Gaza war.

The Israel-Palestine conflict and the environment

The most recent escalation of what is now a 75-year-old issue was the elephant in the COP 28 room. Saudi Arabian Prince Mohammed bin Salman and Palestinian leader, Mahmood Abas skipped their scheduled speeches, as a form of protest, while Jordanian King, Abdullah II, decided to use the COP stage to proclaim his country’s solidarity with the Palestinian people. “This year’s COP must recognize more than ever that we cannot talk about climate change in isolation from the humanitarian tragedies unfolding around us”, he said, unknowingly echoing the voices of the protesters that would gather outside the walls of the conference two days later. On December 3rd, 2023, against the UAE’s limited freedom of speech legislation, more than 100 activists seized the COP 28 platform to call for a ceasefire, declaring that there can be “no climate justice without human rights”.

Speaking to iMEdD, Professor and Senior Research Scholar, Dr. Harry Verhoeven, related this idea to successful climate policy narratives. “The entire way of talking about climate has been so difficult because it’s often so compartmentalized. The single most important thing is democratic conversation and public debate around the trade-offs between policy choices, and at the moment there is little nuanced debate”, he explained, suggesting that despite the attempt to come together during COP 28, the international community is still very divided. He added that arbitrary measures by a single government, a CEO, or a scientist for that matter, can often lack the necessary legitimacy and longevity. In this light, he stressed that it’s challenging if not impossible to address environmental issues without considering the intertwined social, economic and political spheres.

In the case of Palestine, historical land rights, proper democratic processes and technological resilience for climate adaptation should be accounted for a successful climate policy; something that the current conflict poses significant obstacles to.

Water

Throughout Gaza’s history of occupation, the natural flow of groundwater has been severely disrupted. The acute water scarcity, exacerbated by Israel’s control of water sources has led to the over-pumping of the region’s primary underground water reservoir, the Coastal Aquifer Basin. Increasingly outpacing replenishment by rainfall, the relentless pumping has made the water progressively saline, with elevated concentrations of chloride and other chemicals. As a result, 97% of the water in Gaza is contaminated, and therefore is not safe for drinking. According to Dr. Verhoeven, the cause behind unequal access to safe water between Palestinians and Israelis “is clearly not a function of a geographical endowment as it is a function of human choice”, stressing the historical link between occupation and the poor public health system.

In the latest escalation of the conflict, Israel’s bombing has been the cause of the destruction of a staggering 44% of Gaza’s critical water and sanitation infrastructure, including wells and sewage treatment centers. With 130,000 m3 of sewage water having already flown into the Mediterranean and people increasingly drinking and bathing in polluted seawater, the rapid proliferation of bacteriological diseases is now a largely looming threat.

Land and Pollution

From 1992 to 2015, the expansion of artificial land area in occupied Palestinian territory has surged from 1.4% to 4.3%. Because of the limited land available for Palestinians in the West Bank, the previously agricultural plains of Jenin, Tulkarm, and Qalqiliya, have, among others, been converted to urban areas. Such land change has come at the cost of diminishing vegetation cover, rendering occupied areas more and more vulnerable to extreme weather events, including floods and droughts.

Since October 7th, 2023, 65,000 tons of explosives have been dropped on Gaza. Dr. Verhoeven highlighted that “the damage is being done to the already barely existing power grids, the water supply, the soil” but that “there’s also the question of the physical reconstruction of homes and infrastructure”. Indeed, the explosives have dismantled vital climate adaptation technology including photovoltaic panels, thus disrupting the region’s plans to source 60% of its energy from solar power. On top of this, further emissions that are expected during the anticipated remediation of the region are estimated to soar to a significant 5.8 million tons – a fifth of the predicted emissions for the 22-month Russo-Ukrainian war.

“Green warfare”

Israel has systematically uprooted native Palestinian trees and crops, including 800,000 olive trees since 1967. Moreover, 89% of the forests that Israel has planted consist of non-native species. Not only has the import of foreign flora physically westernized the land and removed important traces of cultural heritage, but it has also affected already vulnerable territories. For instance, pines are more susceptible to fires, given their resinous properties, while the shedding of their acidic leaves impedes the growth of underbrush plants, further affecting local biodiversity.

Additionally, Israel has established at least 380 nature reserves and 115 national parks in Palestinian lands to safeguard vital natural, historical, and archeological sites. In reality, while Palestinians are forbidden to cultivate or build within protected areas, Israel has amended the law to allow large construction projects, and paradoxically, even pollution in those lands, unveiling a policy of “greenwashing”.

Adrián Mac Liman, Political Analyst and Middle East expert, told iMEdD that the environmental crisis is a deeply structural issue that concerns us all, not a superficial tear that only a handful of countries can choose to patch up. “Ever since the Oslo Agreements, the environmental situation has been the same, but now there’s escalated conflict and they talk about it. Officials at COP should not look at the environment as a war problem, it’s a permanent problem, and a permanent policy”, he stressed.

“Ever since the Oslo Agreements, the environmental situation has been the same, but now there’s escalated conflict and they talk about it. Officials at COP should not look at the environment as a war problem, it’s a permanent problem, and a permanent policy”.

Gaza: Hell for children

More children have been killed in 49 days of war in Gaza than are killed in all conflicts on the planet annually.

Fossil fuel negotiations: a dangerous “race to the bottom”

“From a strictly diplomatic perspective, there was above all a sense of relief, because if there hadn’t been an agreement reached in Dubai, however imperfect, it would have been seen as yet another crack in the multilateral edifice that we have now”, said Dr. Verhoeven. However, it’s challenging for such an agreement to size up to the magnitude of the task at hand. In the same way it is uncertain whether the $ 85 billion of climate financing raised during the conference will successfully curb emissions. Mac Liman suggested that oil-producing nations “will not be likely to make a genuine compromise about environmental policy. I don’t know to what extent they are going to implement a resolution, not from this year’s COP, I’m talking about the meetings held in the last 40 years”, he added.

A representative example has been the Iranian delegation’s withdrawal from the summit, on December 1st, with Iranian Minister of Energy, Ali Akbar Mehrabian, considering Israel’s presence “contrary to the goals and guidelines of the conference”. Even though this could be expected, since Iran has historically been an enemy of Israel, no country would miss the opportunity of attending COP, according to Mac Liman. The Iranian delegation’s abrupt departure most probably lies in its reluctance to abide by fossil-fuel-free policies, given the importance of the latter to its own economy. Iran has the world’s second largest (17%) natural gas reserves at 33,988 billion m3 and the fourth largest (9%) oil reserves at 158 billion barrels, making the Israeli presence seem like an alibi for quitting the conference.

From a strictly diplomatic perspective, there was above all a sense of relief, because if there hadn’t been an agreement reached in Dubai, however imperfect, it would have been seen as yet another crack in the multilateral edifice that we have now.

Dr. Harry Verhoeven, Professor and Senior Research Scholar at Columbia University’s Center on Global Energy Policy

The UAE’s dual role of conference host and leading petrostate also created debate about the legitimacy of the agreement reached. According to the Kick Big Polluters Out activist coalition, comprising more than 450 climate organizations, at least 2,456 lobbyists were present at COP 28 with a view to discussing and negotiating oil and natural gas deals. This is a significant number once compared to the UAE’s total 4,409 attendees, the Brazilian delegation’s 3,081 attendees and a mere 316 indigenous representatives. Adding another layer to this disparity, US President Joe Biden and Chinese President Xi Jinping were absent from the summit. For Mac Liman, “as long as China and the US, the world’s two biggest polluters, do not make a move, the whole apparatus might become useless”.

However, it was not until conference President and the UAE’s Minister for Industry and Advanced Technology, Sultan Ahmed Al Jaber, claimed that there is “no science out there that says that the phase-out of fossil fuels is what’s going to achieve 1.5C”, that it became clearer how reluctant some governments are in terms of shifting to renewable energy. Ranking as the world’s 10th largest weapons exporter (2.4% of total exports), Israel heavily relies on fossil fuels, with approximately 90% of its electricity production coming from natural gas, oil and coal, as of 2022. Three weeks into the latest conflict escalation, Israel issued licenses to six energy companies, among them the UK’s BP, its own NewMed Energy, Azerbaijan’s Socar, and Italy’s Eni, to further explore natural gas sources along the country’s Mediterranean coast and diversify competition. “Israel has been negotiating this deal with the British companies for the last two years. They decided to sign now, because they have no opposition, because the world is preoccupied with the scale of the humanitarian crisis in Gaza”, Mac Liman explained.

A couple of weeks later, Joe Biden’s Senior Advisor, Amos Hochstein, also stated that “there is an opportunity to develop the gas fields in offshore Gaza, on behalf of the Palestinians”, referring to a deal discussed with Israel in June 2023. Whether this is a deal that will actually serve as a post-war economic revitalization plan for Palestinians is uncertain. Nevertheless, such a development would require coordination from both Lebanon and Egypt, among others. Dr. Verhoeven stressed that “regional actors have for many years tried to shift from historically great energy importers to becoming important exporters, especially of natural gas”. Therefore, while the security dimension is important, viewing the Israel-Palestine conflict through the “prism of a new energy order”, also helps further explain regional dynamics.

And while numerous fossil fuel deals were struck on the way to COP 28, a big chunk of the conference’s discussions focused on carbon capture storage (CCS) and carbon credit solutions; policies that have been largely insufficient. During the conference, Israel’s climate envoy, Gideon Behar, revealed to energy market medium, Argus, that Israel’s tech sector is heavily focused on CCS and offset technologies: “For us, the issue of carbon credits, carbon sequestration is very important”. However, CCS by plants has remained unchanged since 2020 at a low 40 million tons, accounting for only 0.1% of global CO2 emissions in 2022. According to Dr. Verhoeven, CCS has been around for many years, but currently “there is a particular worry, shared by many climate activists, that at the very structural level, it will allow fossil fuel industries to pose as the ‘great saviors’, despite having landed everyone in this hot mess in the first place”.

Similarly, there has been a lot of controversy about whether the carbon credit market can solve climate change, especially given its considerable lack of verification and integrity. Carbon credits are emissions permits, traded between firms or countries, that represent the right to emit, as long as emissions are cut elsewhere in the world, usually in the Global South (1 credit equals 1 ton of carbon dioxide emissions). Although, during COP 28, regulators and top officials from multiple countries supported the adoption of standardized methodologies, to determine who can issue credits and how they can be used more efficiently, carbon credits cannot entirely substitute actual emission cuts, almost providing an easy way for countries to “buy-out” their climate targets.

Αs long as China and the US, the world’s two biggest polluters, do not make a move, the whole apparatus might become useless.

Adrián Mac Liman, Political Analyst and Middle East expert

Upon reflecting on the future, Dr. Verhoeven pointed out that a potential crisis in the Gulf or in the Red Sea can have a twofold effect, similarly to the Russo-Ukrainian war. A global oil trade disruption could force taxpayers and governments into paying the ultimate price because of “inflationary pressures and associated renewed increases of interest rates”, but it could simultaneously encourage “a durable change in production and consumption patterns”, acting as a positive spur for renewable energy alternatives. On a more pessimistic note, Mac Liman predicted a “raging competition for oil and gas reserves in the Mediterranean”, stressing that “the war is ongoing, and the problem is who’s going to get more, not who’s going to get less”. About a month after what proved to be a prophetic discussion with both experts, the Houthi military organization in Yemen, further escalated its attacks on shipping vessels in the Red Sea, in solidarity with the Palestinian people. As a result, the volume of freight containers passing through the Red Sea has dropped by 65% and major oil companies including Shell and Sovcomflot are considering alternative trade routes, creating global panic over the future of European and US markets.

A feeling of reluctance toward effective energy transition, controversial fossil fuel diplomacy and the devastating Israel-Palestine conflict, raise questions about whether this year’s COP focused more on the promotion of political and stakeholder interests, rather than global cooperation for the environment and human rights.