A digital exhibition by the International Press Institute brings to light just a small sample from a true archival goldmine. We spoke with members of the IPI team about the major undertaking of organizing and opening up an archive that chronicles the history of press freedom around the world.

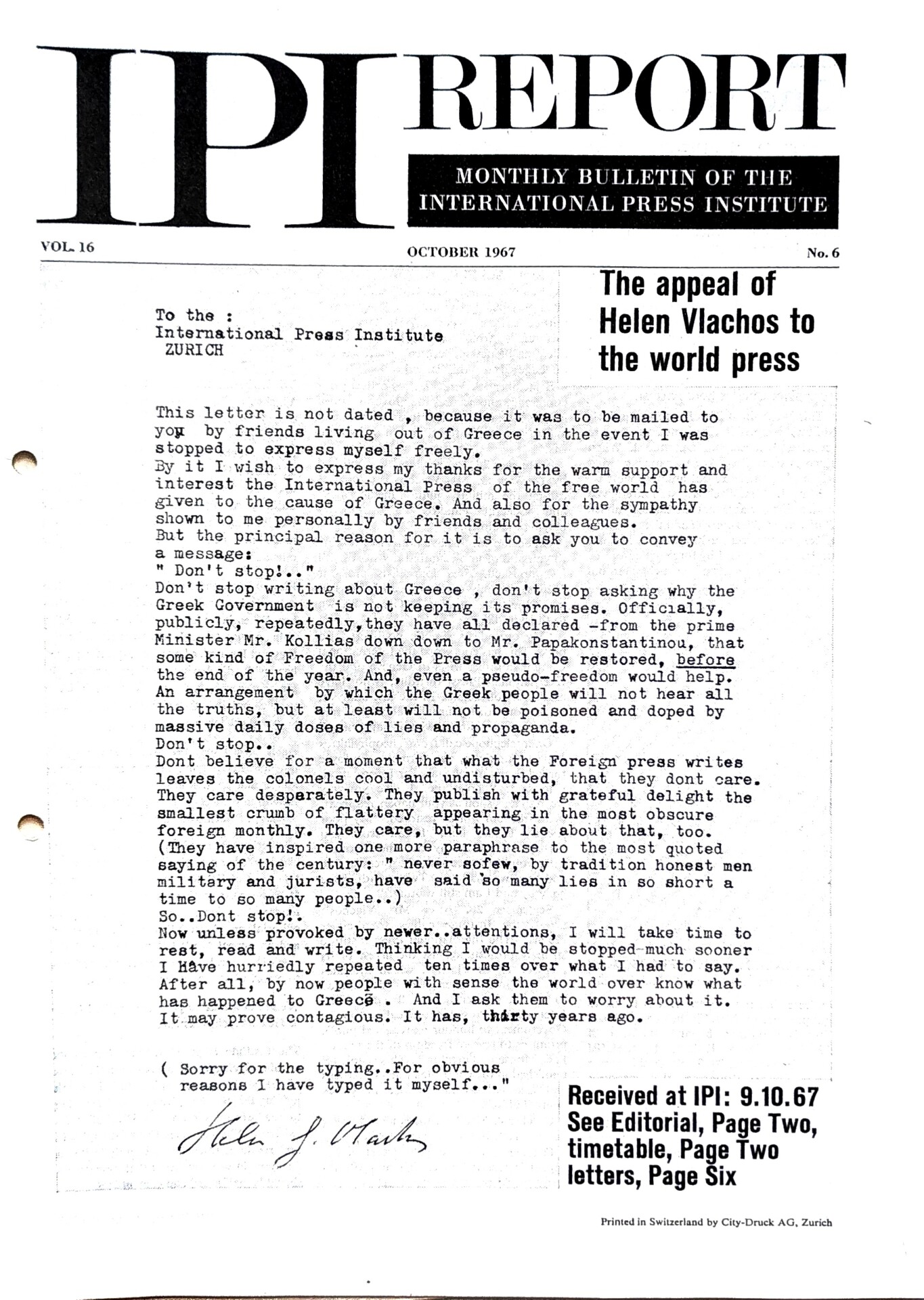

“This letter is not dated, because it was to be mailed to you by friends living out of Greece in the event I was stopped to express myself freely. By it I wish to express my thanks for the warm support and interest the International Press of the free world has given to the cause of Greece. And also for the sympathy shown to me personally by friends and colleagues. But the principal reason for it is to ask you to convey a message: ‘Don’t stop!..’ Don’t stop writing about Greece, don’t stop asking why the Greek Government is not keeping its promises. […] Dont believe for a moment that what the Foreign press writes leaves the colonels cool and undisturbed, that they don’t care. They care desperately. […] After all, by now people with sense the world over know what has happened to Greece. And I ask them to worry about it. It may prove contagious.“

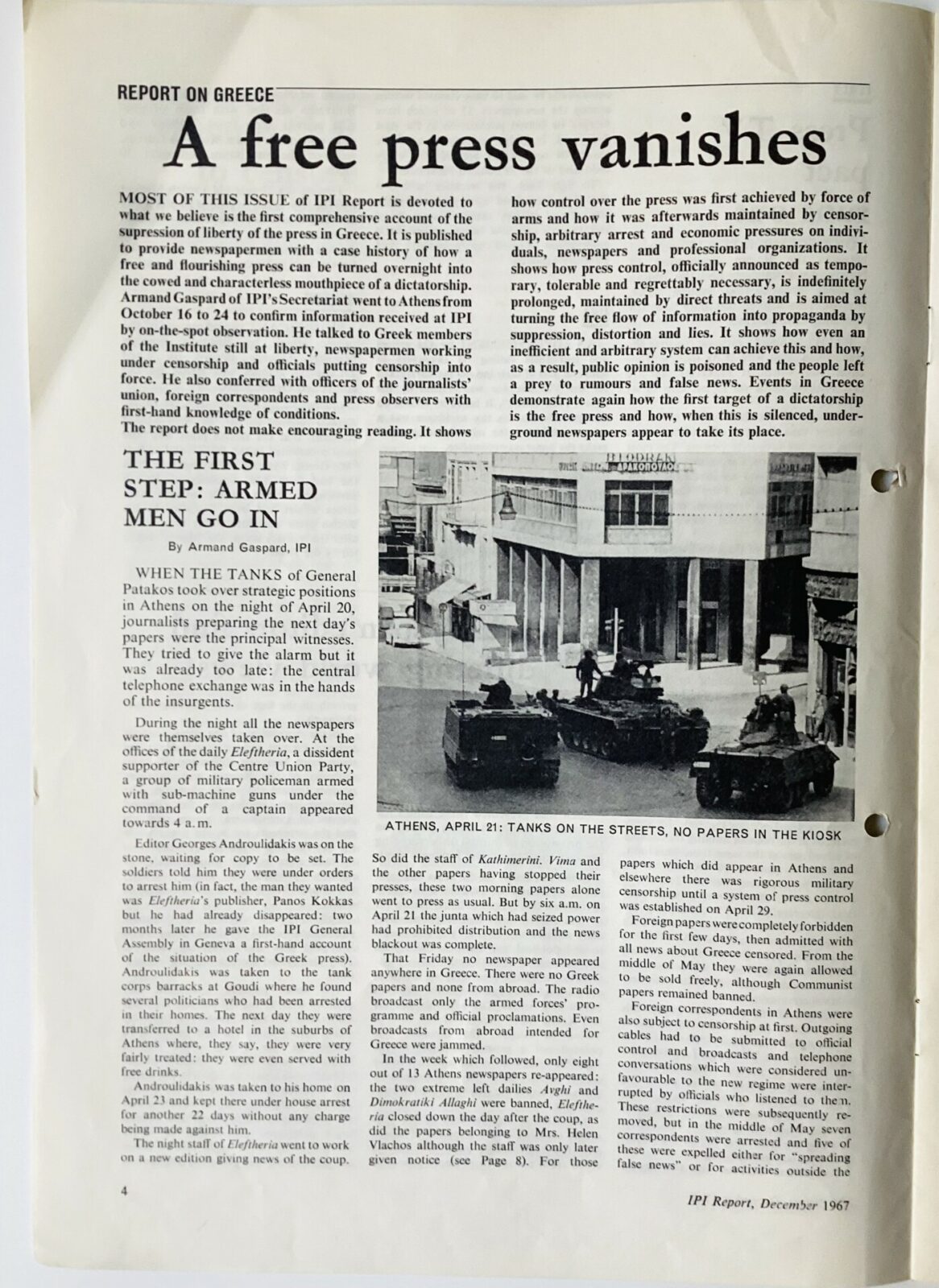

With these words, the historic Greek publisher and journalist Eleni Vlachou (Helen Vlachos) addressed the International Press Institute (IPI) in 1967 —the year she suspended publication of the newspaper Kathimerini in protest against the military coup and was placed under house arrest by the Greek Junta. Her open letter was published in October of that year in the sixth issue of volume 16 of the IPI Report.

Today, Vlachou’s response to the timeless and recurring dilemma —self-censorship or resistance— emerges from the treasure-filled boxes of the IPI’s historical archive. It is just one of the documents featured in the digital exhibition titled “IPI 75: Solidarity, innovation, resilience,” which has been freely available online since late November, following its physical presentation —attended in person— at the 75th IPI Anniversary World Congress and Media Innovation Festival in Vienna in October 2025.

“In the more than seven decades since IPI was founded, we have produced an unparalleled archive that traces the evolution of the global media landscape. This collection offers a unique window into the historical movement to protect and strengthen press freedom worldwide,” wrote Gabriela Manuli, IPI’s Director of Special Projects, in the Institute’s newsletter last November.

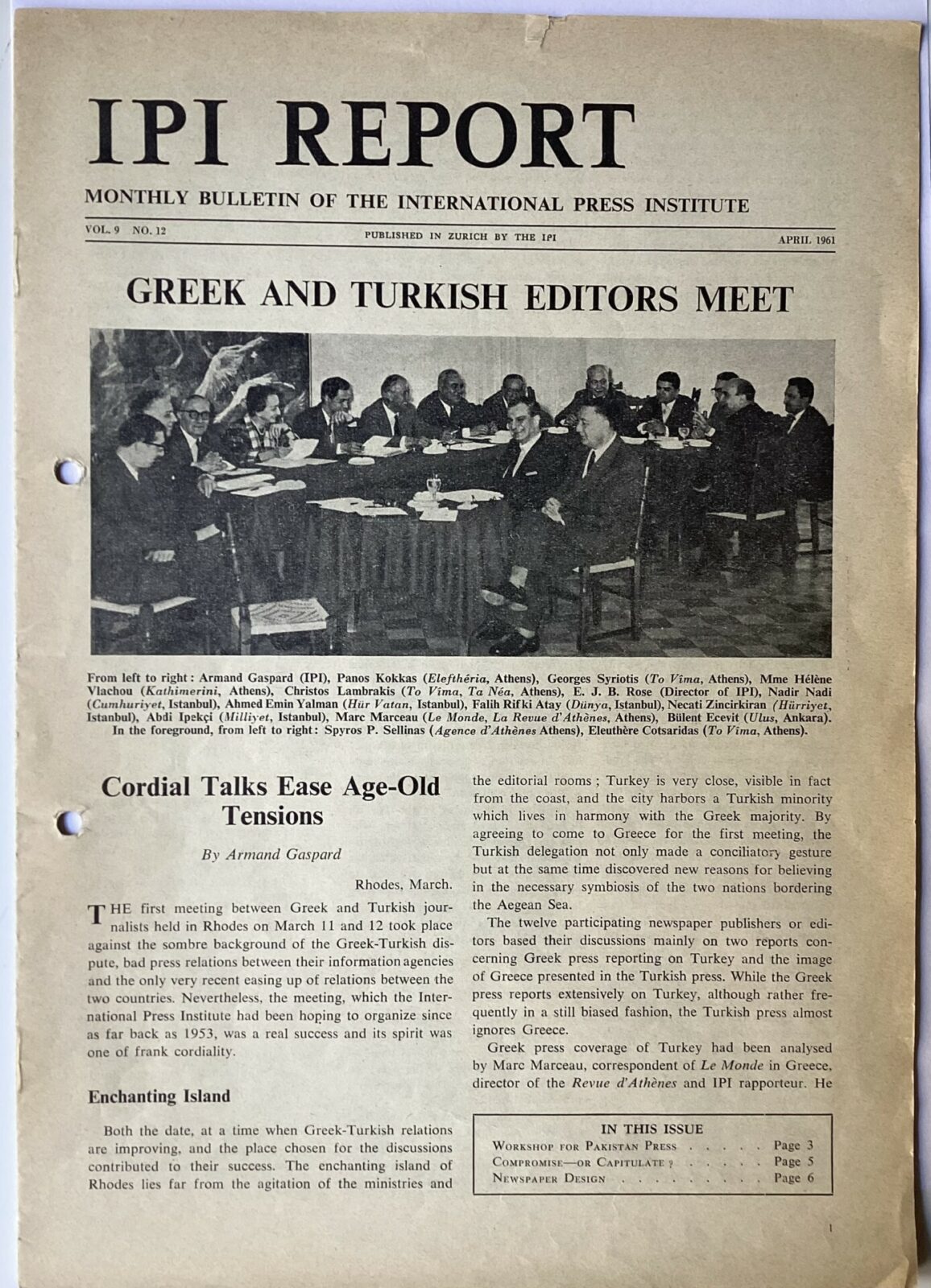

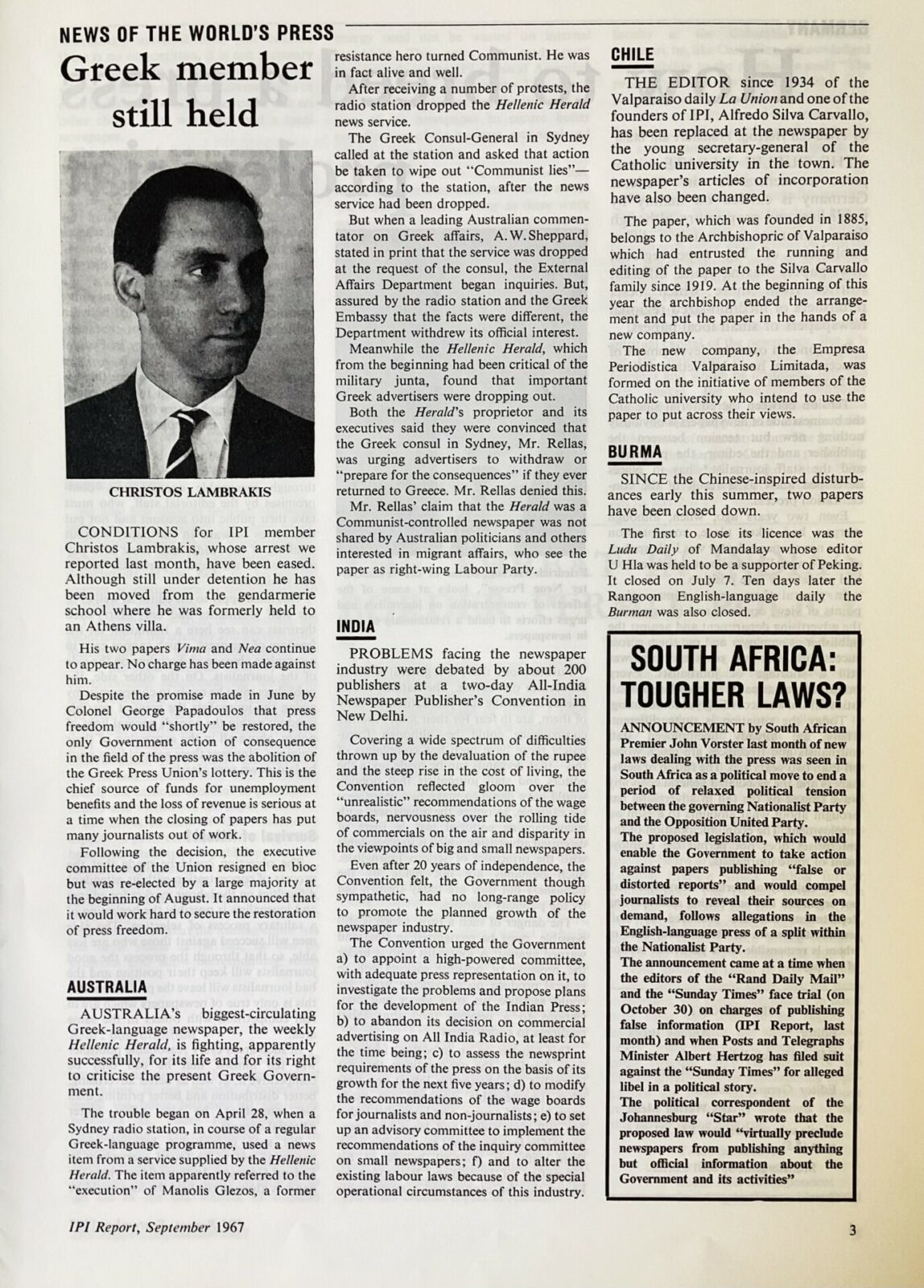

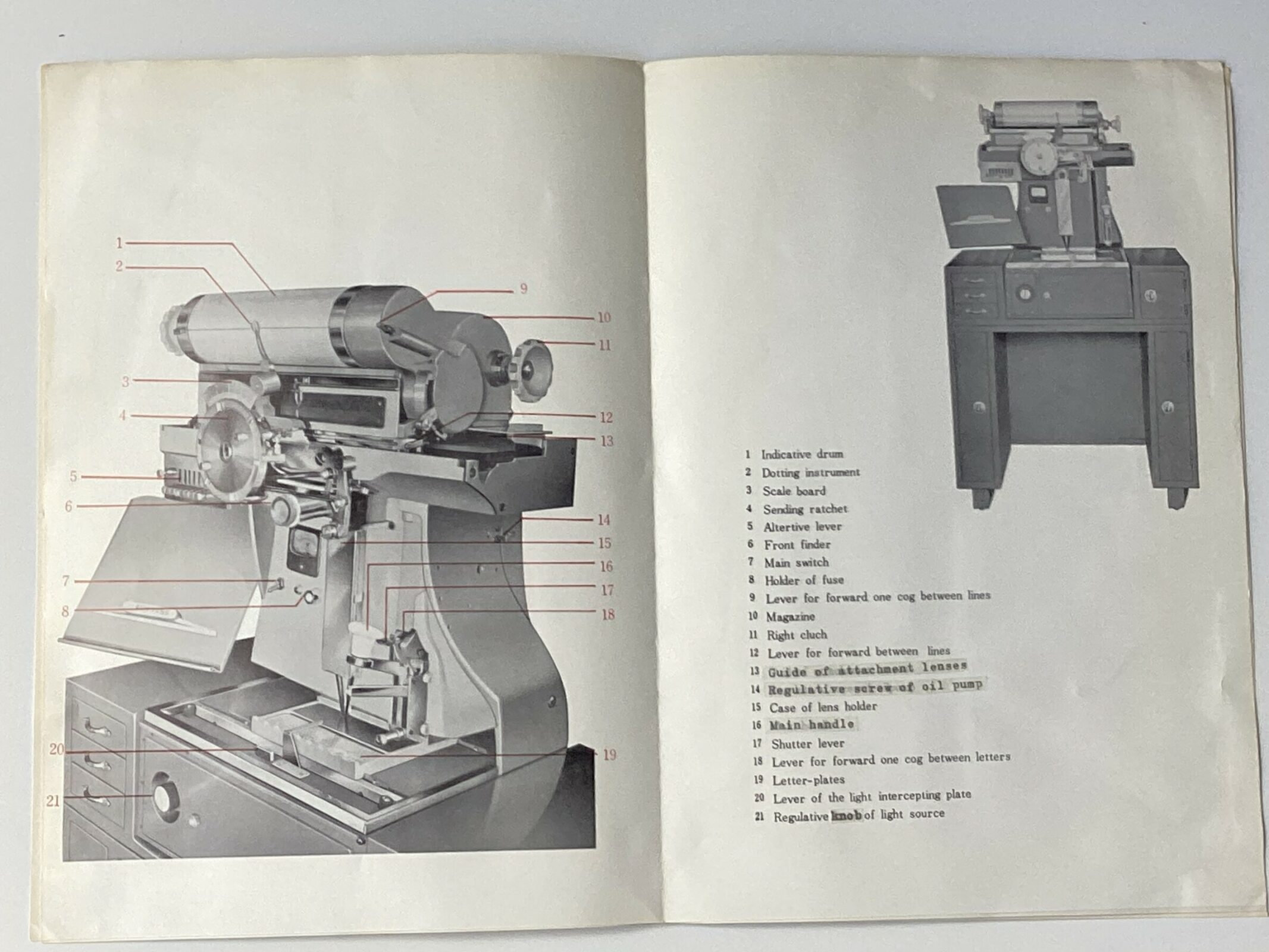

Indeed, among the indicative snapshots are: the first meeting of Greek and Turkish editors under the IPI umbrella in April 1961; a handshake between French President Charles de Gaulle and German Chancellor Konrad Adenauer; protests at the Berlin Wall in November 1989; Nelson Mandela’s address at the IPI Congress in Cape Town in 1994; and the presentation of new multicolor printing machines at the IPI General Assembly in Tokyo in 1960. These moments only scratch the surface of what is included in the exhibition’s three thematic chapters: turning points, censorship, and technological change.

This exhibition is not just about IPI. The archive is not just the history of IPI. This is the history of press freedom around the world. This is why IPI exists.

Gabriela Manuli, Director of Special Projects, IPI

“This exhibition is not just about IPI. The archive is not just the history of IPI. This is the history of press freedom around the world. This is why IPI exists. IPI was there, witnessing, working on this issue, but a lot of the things are wider,” Manuli tells iMEdD, before continuing with passion: “We are talking about this recurring crises; and we sometimes realize that the discussion we were having 50 years ago about a technology, for example, are the same conversations we have again 20 years later [about a new one]. You see all these crises, but you also see how resilient journalism is. We keep surviving, adapting —and, I think, we need to learn from our past. We also need to deconstruct the past. This is a lot of what we are doing with the gender aspect of the exhibition.”

She is referring to the exhibition’s second section —also drawn from the IPI archive— titled “Honouring the pioneers: Four decades of exceptional women at the IPI General Assembly.” “It is about the history of women in journalism and how it was evolving. In fact, at some point, IPI was really pioneering in having strong female voices. We need to learn from the past, deconstruct it, and make it available, so that people can continue.”

These exhibitions —described as a “mid-term dream”— offer only a first glimpse into what is contained in an archive that is, as Manuli puts it, “a real goldmine.” At IPI’s offices in the Austrian capital, housed in a 19th-century Viennese building, the high-ceilinged Press Freedom Room holds it all: IPI Reports, photographs and images, floppy disks, video and audio recordings of past congresses, correspondence from IPI members, surveys and studies, cartoons, administrative and financial documents, and much more. “You walk through the office, and you have history,” Manuli says vividly.

“Archives are measured in ‘archival meters,’ based on the length of the shelves they vertically sit on. The IPI archive measures around 30 meters. [The Press Freedom Room is about] three to three-and-a-half meters high, which is ideal for archival holdings —you can just stack stuff up. There are two walls with shelves on. Everything is organized quite carefully, but the boxes are of different sizes and stacked like Tetris. The boxes of correspondence, for example, are organized into mini paper folders. These materials are very old, and the paper is super thin, because people were sending letters and needed to keep costs down. That means you can fit a huge volume of correspondence into one box —it’s like a terabyte in today’s [terms],” explains Gwen Jones, archival researcher and curator of the IPI archive, giving a sense of the archive’s scale.

You see all these crises, but you also see how resilient journalism is. We keep surviving, adapting —and we need to learn from our past. We also need to deconstruct the past.

Gabriela Manuli, Director of Special Projects, IPI

With a background in history and international relations and long experience in archival research, Jones joined the IPI team in early 2025 specifically for the project of researching, cataloging and, eventually, digitizing the archive. “The long-term dream is to digitize all this material —to make it searchable and accessible,” Manuli says, envisioning a digital platform that will host the global history of persistence in defense of press freedom. Of course, this is far from simple. It requires partnerships with academic and technological institutions, fundraising, and time.

Digitization, after all, comes only after several crucial preparatory stages. “Journalists work quite fast and archivists quite slowly,” says Jones. “Before we start digitizing, we need to open every single box in the archive and catalog [the material]. It’s actual unboxing: you open up a box that hasn’t been opened since the ’50s. I joke [that we’re dealing with] dust from the ’50s.” The first phase of the project is the creation of an index —a general inventory that can only be produced once the team knows and has recorded exactly what the entire archive contains. Jones is currently immersed in this process, which may take more than six months.

It’s actual unboxing: you open up a box that hasn’t been opened since the ’50s. I joke [that we’re dealing with] dust from the ’50s.

Gwen Jones, archival researcher and curator of the IPI archive

“And then [comes] digitization. There are companies that can digitize very fast, but you have to tell them exactly what you want. It’s like using artificial intelligence: if you have it under control and tell it what to do, it does what it’s supposed to,” Jones notes. “We could spend three —or even five— years on this. The aim is to ensure that everyone who is interested can find not only the history of IPI, but the history of monitoring press freedoms, of organized state violence against journalists, of technological change, of attempts to control the flow of information —how journalists have confronted technological change since the ’50s, what has endured, what works, how journalists work together, or don’t work together. These issues are important, especially now, and we want to make sure that everything is searchable.”

Jones is the person who has truly dived into the IPI archive. We ask her to recall a moment when she was genuinely surprised while leafing through its contents. She remembers: “I was looking at [the materials from] the 1958 IPI Congress and saw that the lunchtime address was given by one ‘J. Robert Oppenheimer.’ I was like, ‘you’ve got to be kidding me.’ But it was him. I then found his speech. I flipped over to the other side of the programme and saw another address by the [then] President of the United States, Eisenhower —and I found his original speech too, on the original paper. And the paper is enormous. It doesn’t fit into folders. So, I make the joke that this is a size of paper only U.S. Presidents are allowed to use —it’s just far too big.”

There are companies that can digitize very fast, but you have to tell them exactly what you want. […] The aim is to ensure that everyone who is interested can find not only the history of IPI, but the history of monitoring press freedoms, of organized state violence against journalists, of technological change, of attempts to control the flow of information.

Gwen Jones, archival researcher and curator of the IPI archive

We often say that we have much to learn from the past, or that history is always both instructive and relevant. Perhaps we do not fully grasp this idea until we encounter a tangible example —such as an excerpt Jones recalls finding in an IPI Report from 1953: “Newspapers risk becoming lifeless tools in the hands of a demagogue unless editorial methods are revised to handle The Big Lie.”

“When I read that,” she says, “I thought it could have been published last week.”

Featured image: Collage of images from the IPI archive. Courtesy of IPI. Illustration by Eugenios Kalofolias.

The article is published by iMEdD under a Creative Commons licence (CC BY-NC 4.0).The images included are courtesy of the International Press Institute (IPI) and are provided for the purposes of this publication. Any other use by third parties requires prior communication with IPI.