The Bad Blue Boys, hooligans associated with Croatian club Dinamo Zagreb, who are accused of the deadly incident in Nea Filadelfeia, Athens, have links to organized fans from Ukraine and Greece. An in-depth investigation conducted by iMEdD delved into numerous public channels and social media profiles to uncover the connections between organized fans from Croatia, Ukraine, and Greece, as well as their affiliations with far-right ideologies. The research has shed light on how the Telegram platform serves as a catalyst for networking among these groups, potentially playing a role in recruiting new members for the far-right hooligan movement.

Before Lavriou, there was Ymittou: The fight that led to Filopoulos’ Murder

“For the first time, we understood how our opponents think” – a video that endures till this day marked the onset of a new, more aggressive era of hooliganism in Greece.

On the evening of August 7, 2023, 29-year-old AEK fan Michalis Katsouris would lose his life during clashes outside the stadium of his beloved team in Nea Filadelfeia. The following day, AEK was scheduled to play one of the biggest Croatian football teams, Dinamo Zagreb, in the third qualifying round of the UEFA Champions League. More than 100 die-hard fans of the Croatian team crossed four countries by road and arrived in Athens, defying a UEFA-imposed ban on away supporters for this particular match. One dead, 29-year-old Michalis Katsouris, and many injured is the result of the murderous raid by the self-styled Bad Blue Boys (BBB) on the evening of 7 August 2023. Police made 105 arrests, of which 102 were Croatian members of the Bad Blue Boys.

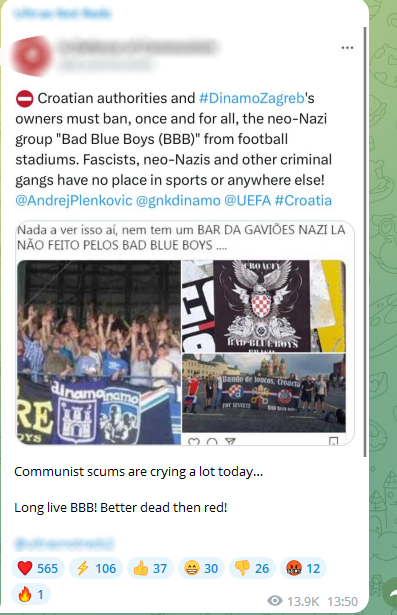

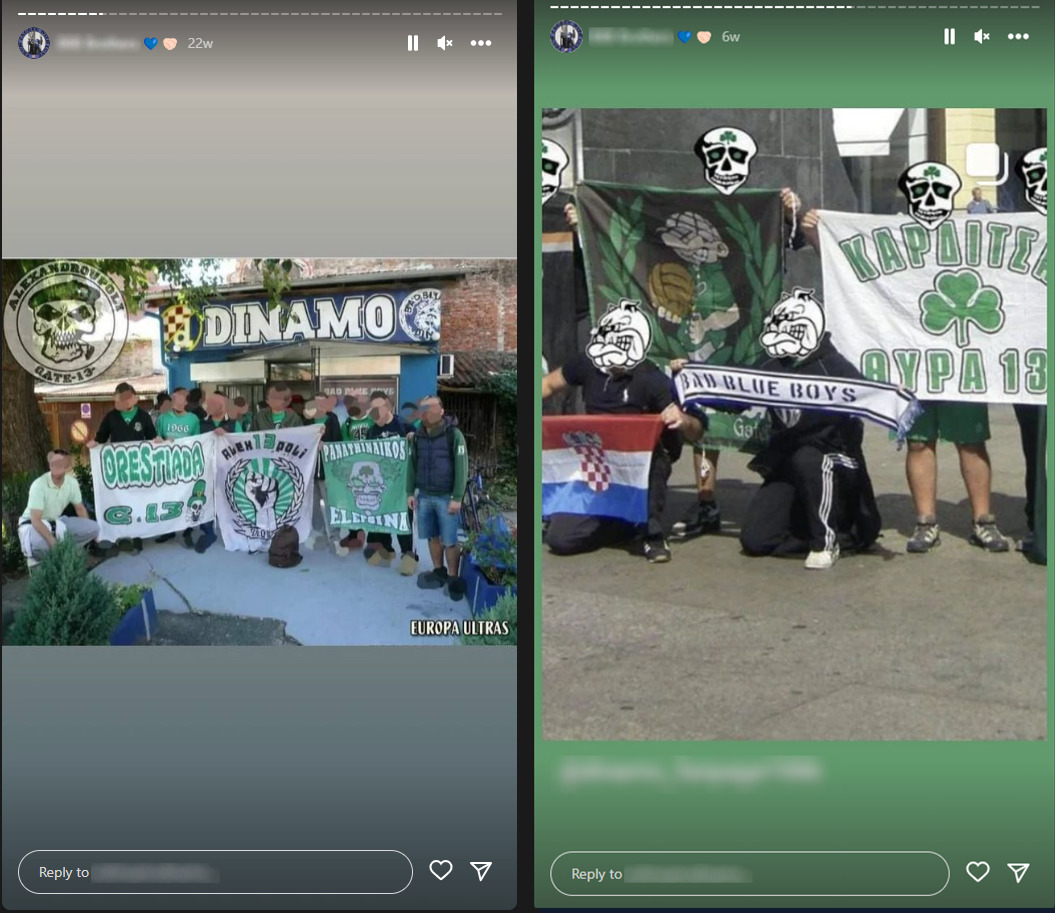

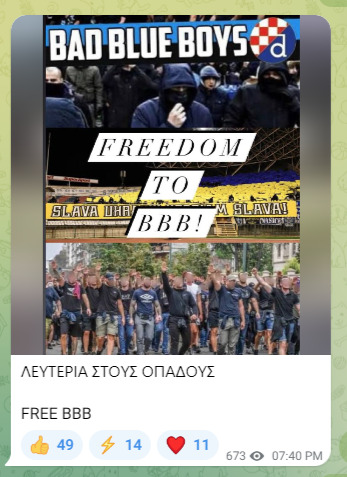

The Bad Blue Boys (BBB) have constructed a “mythology” around their name within the realm of organised and passionate fans in Southeast Europe. Dario Brentin, a researcher specialising in politics and football in the Balkans, notes, “There is a predisposition towards violence on their part and a predisposition towards more militant expressions of fan culture.” During their journey to Athens and the subsequent violent incidents outside the Nea Filadelfeia stadium, the Croatian Bad Blue Boys purportedly collaborated with Panathinaikos fans, with whom they maintain ongoing contacts. Brentin further elaborates that these connections between groups of fervent fans, often referred to as “twinning” in fan parlance, can emerge from shared jersey colours or even something as simple as a shared night out. Such affiliations, however, may also be rooted in shared political stances among fans. In addition to their ties with a segment of Panathinaikos fans, the BBB also seem to have close associations with fans of the Ukrainian football team Dinamo Kiev. These fans have openly expressed their support and solidarity with the Croatian ultras arrested in connection with the events in Nea Filadelfeia.

The Bad Blue Boys’ ties with fan groups from Ukraine and Greece have been substantiated through online posts and social media platforms. Notably, Telegram, a global instant encrypted messaging platform that prioritises user privacy, emerges as a preferred mode of communication and networking among organised fan groups and hooligans. It serves as a means to share their exploits and coordinate activities. Alexander Ritzmann, who leads the Counter Extremism Project’s office dedicated to addressing extreme-right violence and terrorism, conducts research aimed at preventing and countering far-right networks, both in the physical and digital domains. As Ritzmann tells iMEdD, Telegram provides a “relatively safe space” for its users, owing to its minimal content control practices. However, this characteristic can also make the platform attractive to extreme and violent groups.

But that’s not all. Through an extensive examination of more than twenty public Telegram channels and dozens of other social media profiles following the events of August 7, iMEdD has brought to light the intricate network of connections that exist between organised fan groups and hooligans, such as the Bad Blue Boys, and the far-right.

“From trenches to Athens”

“AEK is well-known for its leftist views (…) That’s why we are not ‘mourning’ in any way, but, primarily, we take pride in our brothers. We will have a lot of work ahead of us in Europe after the war.” This message, posted on August 8 by a Telegram channel affiliated with fans of the Ukrainian football team Dinamo Kyiv, reflects on the occurrences in Nea Filadelfeia. The channel is linked to the Ukrainian hooligan group “ALBATROSS”, which lends support to and advocates for organised fan groups engaged in the Ukrainian front amidst the Russian invasion of the country.

The following day, the same page shared a photo displaying military shells with the inscriptions “FREE BBB” and “From trenches to Athens respect and pride.” The accompanying description stated, “Two years ago, alongside our Croatian brothers, we were apprehended during an unsuccessful attempt to attend an away game in Poland. Today, we find ourselves in the trenches, observing Dinamo Zagreb’s victory over the leftist scum on their home turf (editor’s note: referring to the events in Nea Filadelfeia). We extend our well-wishes to our brothers, urging them to stand firm, and we are committed to standing with them. Post-conflict, our actions in Europe are assured.” In a similar post on March 18, they celebrated the 37th anniversary of the Croatian Bad Blue Boys, portraying them as “the best of friends who assisted the Ukrainian nation during challenging times.”

Forming Brotherhoods Online

The relations between hardcore Dinamo Zagreb fans and Ukrainian hooligans extend beyond just “ALBATROSS.” The Croatian Bad Blue Boys maintain close connections with the self-styled “White Boys Club” (WBC), ultras of Dinamo Kyiv. The use of hate symbols and sporadic racist incidents within the Ukrainian team’s ultras stands are indicative of their ideological leanings. The WBC group is linked with Ukraine’s far-right political party, the National Corps, and the military unit of the National Guard within the Ministry of Internal Affairs of Ukraine, known as the Azov Regiment, which has garnered controversy due to its affiliation with neo-Nazism. In April 2021, the National Corps party announced, via Telegram, the participation of the White Boys Club in a tactical military training seminar, which included instruction in knife fighting.

Robert Claus is a researcher delving into the intersection of fan culture and politics. During a Zoom call, he discusses the pivotal role of social media, including Telegram, as indispensable networking tools for far-right hooligan groups throughout Europe. The Ukrainian hooligans of Dinamo Kyiv, represented by both “ALBATROSS” and “WBC,” are no exception: Their Telegram posts have since expressed support and solidarity for the detained Croatian members of the Bad Blue Boys. Furthermore, evidence of their connections emerges from posts in international far-right public Telegram channels, which also stand in solidarity with the fans of Dinamo Zagreb.

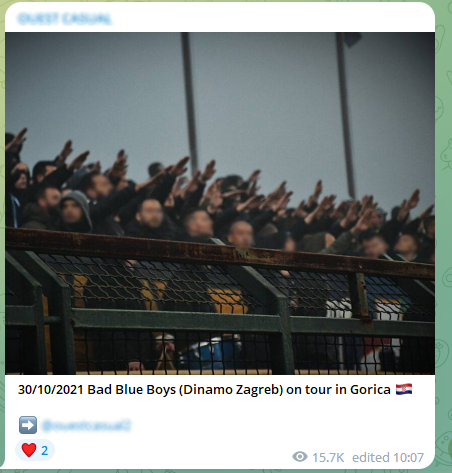

In fact, the amicable relations and networking between the BBB and fans of Dinamo Kyiv and Panathinaikos are also confirmed by a document issued by the Hellenic Police (ELAS). ELAS had been aware of the potential presence of Croats in Greece since August 4. The document also notes that during a previous away game of Dinamo Zagreb in 2019, a Croatian team’s fan made a Nazi salute.

Hooligans and Politics

“Several right-wing extremists have either been or continue to be hooligans. The common thread linking these two communities is violence, and in this regard, organised fan groups can serve as recruitment pools for far-right groups,” says Alexander Ritzmann of the Counter Extremism Project to iMEdD. Platforms like Telegram can exacerbate this issue. “Certain ultras groups and hooligans function as hubs, frequently sharing (editor’s note: on Telegram) content originating from far-right groups, thus aiding in potential recruitment,” he adds.

According to Robert Claus, there are three primary Telegram channels for far-right hooligans in Europe, each boasting hundreds of thousands of followers. iMEdD conducted research on these channels and discovered that all three have shared actions by the Bad Blue Boys, with many of the posts also emphasising the political views of the Croatian fans. Furthermore, two of these three channels have also disseminated content regarding the events in Nea Filadelfeia, showing support for the detained Dinamo Zagreb fans.

Several right-wing extremists have either been or continue to be hooligans. The common thread linking these two communities is violence, and in this regard, organised fan groups can serve as recruitment pools for far-right groups

Alexander Ritzmann, head of the Counter Extremism Project’s office dedicated to addressing extreme-right violence and terrorism.

The Greek “brothers”

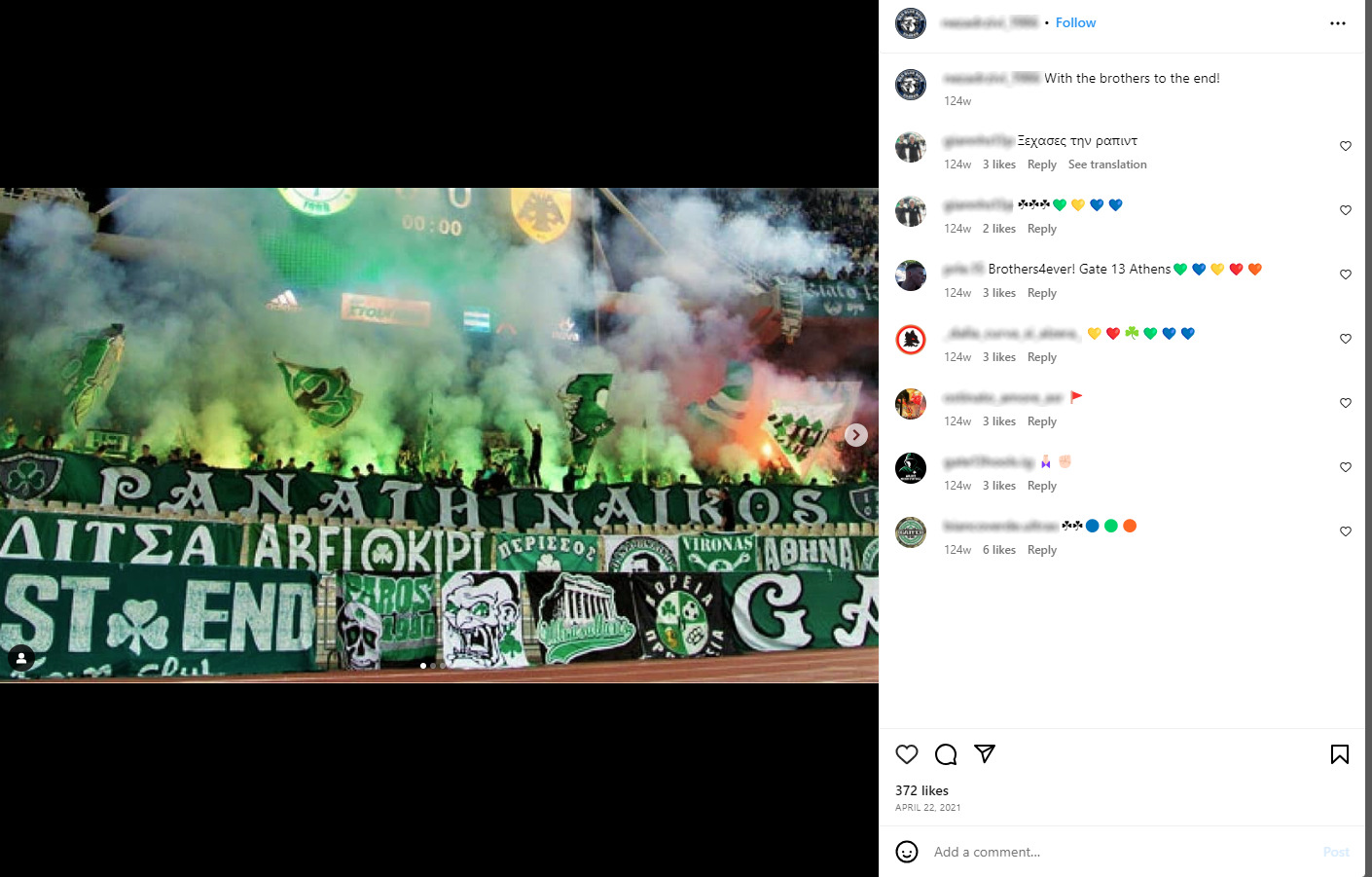

The “mythology” surrounding organised fans suggests that the connections between Panathinaikos and Dinamo Zagreb fans date back a few years when they were in Italy to attend a football match hosted by Roma, with whom both sets of fans share friendly relations.

Upon investigating open Instagram profiles associated with the sphere of organised Dinamo Zagreb fans, iMEdD substantiates the connection between Greek and Croatian fans.

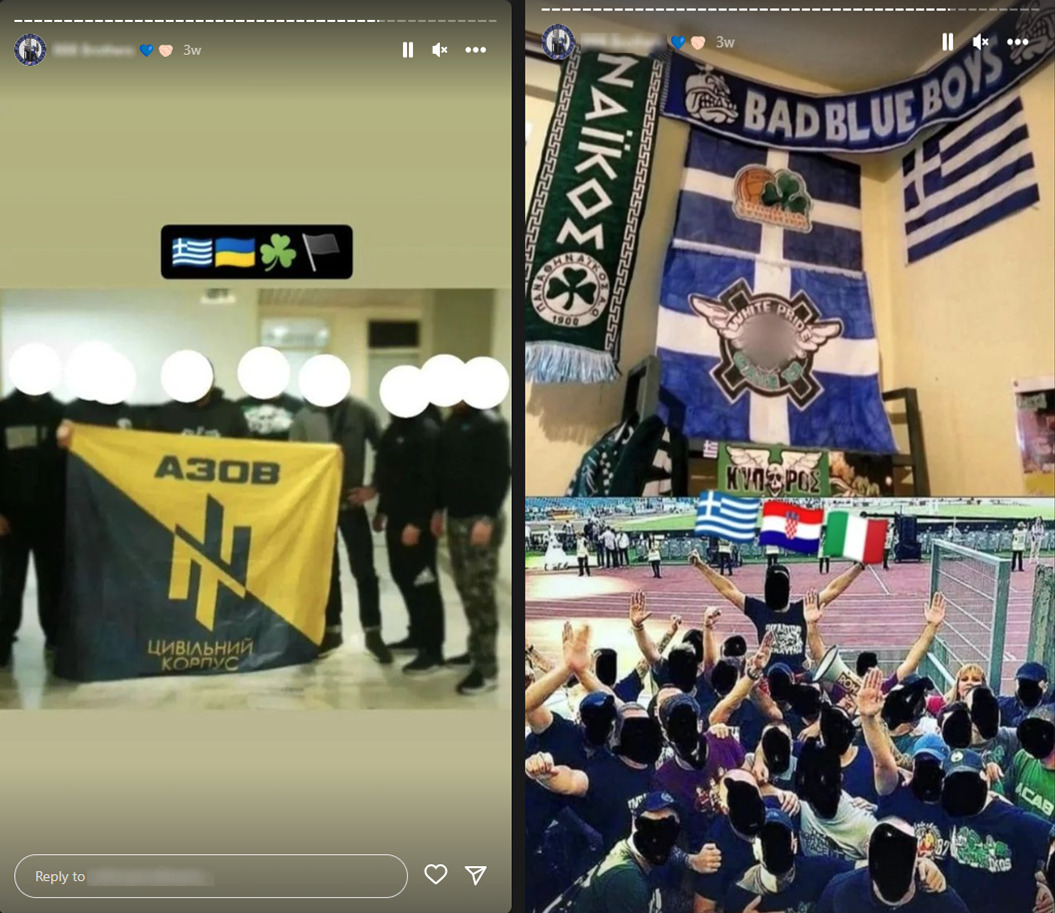

In a photograph shared by a profile affiliated with the Dinamo Zagreb fan movement and the Bad Blue Boys, individuals purported to be Panathinaikos fans are seen holding an Azov Regiment flag featuring the Wolfsangel rune, widely considered a neo-Nazi hate symbol by numerous scholars. A story posted by the same profile displays fans with obscured faces, some wearing Panathinaikos shirts, making Nazi salutes. The image includes the flags of Greece, Italy, and Croatia, with another photo at the top showcasing scarves and flags representing Panathinaikos and the Bad Blue Boys. One of the Greek flags bears the words “White Pride,” while the far-right symbol, resembling the Celtic Cross, has been digitally removed. This symbol is utilised by several far-right and neo-Nazi organisations across Europe and the United States, including Golden Dawn.

The “Political Persecution” of the Bad Blue Boys

In many instances, however, the backing for the Croatian involved in the Nea Filadelfeia clashes exhibits distinct political undertones. Greek far-right factions, identifying themselves as national socialists and belonging to the “autonomous nationalists,” have also expressed support for the detained Bad Blue Boys, characterising their situation as “political persecution,” and sharing messages of solidarity on Telegram channels and other platforms.

We’ve directed inquiries to the Cybercrime Division and the Sub-Directorate for Countering Violence in Sports Venues of the Greek Police, both concerning these groups and their online activities, and regarding the potential existence of far-right groups within the organised Panathinaikos fan community. As of the time of this publication, we have not received any response.

According to Brentin, who works on the nexus of football and politics in the Balkans, pinpointing a single political ideology as the pivotal element of the Bad Blue Boys’ identity isn’t straightforward. “Certainly, they are a right-wing group, with an openness to fascist and xenophobic ideas, although these factors do not exclusively define their identity.”

Certainly, they are a right-wing group, with an openness to fascist and xenophobic ideas, although these factors do not exclusively define their identity

Dario Brentin, Researcher specialising in politics and football in the Balkans.

The world of Telegram in Nea Filadelfeia

The numerous Telegram channels collectively form a community, a network that can function as a digital “backdrop” that becomes evident in incidents like the one in Nea Filadelfeia. It facilitates communication among violent and extreme groups, allows them to imitate each other, and serves as a safe haven for them to boast about their violent actions afterward.

According to Ritzmann, what sets Telegram apart from other platforms and social media, such as TikTok, is its absence of algorithmic amplification and content promotion. This characteristic positions Telegram as a tool for more “internal propaganda and content distribution” within the confines of the far-right community’s members.

Robert Claus highlights violence as the main factor in the communication of these groups, which is achieved through platforms such as Telegram. “Violence is a means of communication for these groups. It’s a way to acknowledge their masculinity, a way to pride themselves and show how strong and violent they are.” According to him, this communication mechanism can lead to a competition between hooligan groups – a competition over who is the most violent in real life.

Of course, this competition can lead to a continuous pursuit of increasingly violent incidents, all with the goal of presenting each hooligan group as more robust, audacious, and dedicated to their beliefs and ideology than the others. “These groups (editor’s note: referring to hooligan groups) engage in a contest to determine who is the most formidable and adept at violent acts. The real-world violence and the violence that unfolds on social media are closely intertwined,” Claus further adds.

It’s possible that the Croatian hooligans who travelled to Greece for the match against AEK viewed it as a challenge and an opportunity to demonstrate the resilience of their fanbase. For a group of at least a hundred fans to successfully navigate through four different countries without interference, despite the UEFA travel ban, and to confront a rival group of fans outside their home stadium, is highly regarded as a significant ‘badge of honor’ in the hardcore hooligan world. This is especially true when the rival team is perceived as ideologically antagonistic. Before concluding our discussion, Dario Brentin adds, “I would say it’s a factor. Perhaps not the root cause, but I believe politics did play a role, to some extent or another.”

Translation: Anatoli Stavroulopoulou