Betsy Ladyzhets, a data journalist covering science issues, talks to us about her website, the community she built around it, the sustainability and future of the project, and her key findings regarding the quality of American COVID-19 data.

I want to explain current patterns in COVID data to lay readers in a way that will help them understand what’s going on with the pandemic in their communities. I want to provide resources and story ideas to the journalists and I want to promote broad transparency and accountability for COVID data.

Betsy Ladyzhets

“Welcome back to the COVID-19 Data Dispatch with me, your local angry data nerd, Betsy Ladyzhets,” writes journalist Betsy Ladyzhets in the introduction to the now regular email we receive every Sunday from the COVID-19 Data Dispatch. The latter is an independent, online self-publication that has been bringing together all the news about the pandemic in the U.S. since July 2020, including the latest available data from public health agencies and new online data sources, while also laying out the challenges faced by data journalists covering the pandemic. COVID-19 Data Dispatch (CDD) is what its title suggests: a weekly newsletter on pandemic data in the form of a blog like website.

The idea and goals

A data journalist specializing in science (until recently she had been managing Stacker’s Science & Health section), Betsy Ladyzhets, who is the founder and editor-in-chief at CDD, has been focused on reporting on COVID-19 for the past year. She was also one of the many reporters volunteering for the COVID Tracking Project, an Atlantic initiative that has been a benchmark for collecting and publishing data regarding the spread of COVID-19 in the United States.

The idea to create the CDD, whose content is open and licensed under a Creative Commons CC BY 4.0 license, came about after a specific incident in July 2020: “The tracking of COVID-19 hospitalization data in the U.S. was moved from the CDC, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, to the HHS, the Department of Health and Human Services –which is a parent agency for the CDC. The short version of this story is, HHS leadership saw a lot of issues with CDC data collection practices (they weren’t getting data from all hospitals in the country, a lot of information was missing from the hospitals that did report, there weren’t updates on a daily basis, etc.) and decided to take over using a newer data infrastructure. But at the time, the transfer of responsibility was made out to be this huge political story –like, Trump’s administration was taking data out of the hands of the CDC, now we can’t trust the data, that kind of thing. (You can read my write-up of the situation here.)” Betsy Ladyzhets tells the iMEdD Lab.

She goes on to explain: “For me, the incident became a wake-up call: I realized that, while I’d been living in this little bubble with all my fellow COVID Tracking Project volunteers and science/health journalists who had a decent understanding of how the COVID data world worked, a lot of other Americans were just so confused and concerned about these numbers. That included a lot of other reporters, like local journalists and political journalists who got pulled onto the COVID beat. This realization led me to think, ‘well, I don’t blame folks for being confused. But I’ve been following the data closely for a few months now, I have a pretty good understanding of the issues, I can take a stab at explaining what’s going on’. Besides that, I was in a position where I could not freely write about niche data issues at my day job and could not do more voice-driven, opinionated writing at the COVID Tracking Project, so I wanted my own outlet to do that very specific writing”.

Anyone can gain data fluency, and public health agencies should encourage such fluency by making their data easy to access and clearly understandable.

Consumed with these thoughts, Betsy Ladyzhets created a poll on her Twitter profile: “If I started a newsletter on covid-19 data, would anyone be interested?” she asked her followers on 21 July 2020 and, less than a week later, the CDD’s first issue was published. Since then, Ladyzhets has been running the CDD with three goals in mind: “First, I want to explain current patterns in COVID data to lay readers in a way that will help them understand what’s going on with the pandemic in their communities. Second, I want to provide resources and story ideas to the journalists and communicators in my audience –I want them to amplify the issues I present. And third, I want to promote broad transparency and accountability for COVID data. I strongly believe that anyone can gain data fluency, and that public health agencies should encourage such fluency by making their data easy to access and clearly understandable. I hope anyone reading my work is learning something about how to interrogate data each week, making them better equipped to understand statistics about their community”.

Workflow and data sources

At the beginning of each week, Betsy Ladyzhets starts taking notes, using ideas and links to resources for the upcoming issue. Around mid-week, she meets with intern Sarah Braner to discuss and decide on key issues and, towards the end of the week, Betsy, who takes on one major story and several smaller ones weekly, writes her pieces. On Sunday morning she finishes the editing process and publishes the pieces on the site before she sends out the newsletter with the major stories. She uses specific applications to monitor usage statistics for both the newsletter and the website and has set up automated detection to avoid wasting time on non-journalistic material.

When it comes to finding datasets and sources for the content she publishes on the CDD, Betsy Ladyzhets highlights the advantages of building a network of reporters and communicators who follow the pandemic developments: “I have Twitter notifications turned on for the White House COVID-19 Data Director, Cyrus Shahpar, because I know he always posts when new federal datasets are released. Same thing for Drew Armstrong, who runs Bloomberg’s vaccination dashboard –he shares all the major updates on that type of data. There are also other newsletters I pay attention to, such as Covering COVID-19 at Poynter, POLITICO Pulse, and Data Is Plural, which often include COVID-19 datasets and updates. And then, I’ll often see datasets or updates on my Twitter timeline or in another community space, like the Slack server for COVID Tracking Project volunteers”. Having first-hand experience of the confusion created when trying to use data to answer questions about pandemic trends in the US, Betsy carefully reads the methodology notes and press releases to identify various issues in the COVID data provided by the government.

Fewer than five states report enrollment numbers, and only one state, New York, reports testing numbers. Without such data, it’s difficult to contextualize the case counts that are more commonly reported.

Betsy Ladyzhets

In this country, we are not actually dealing with one singular, standardized system. We’re instead dealing with 56 smaller systems (50 states and 6 territories). Each system has its own rules, its own reporting practices, its own data definitions.

Betsy Ladyzhets

I envision my work shifting to have a more global focus –much of the world won’t get vaccinated until 2022, after all. Thanks to climate change and the increasing likelihood of all kinds of natural disasters, I know that COVID-19 will likely not be the only pandemic in my lifetime.

Betsy Ladyzhets

Glossary of statistical terms for beginners

A glossary of basic terms for the beginners in data analysis and for anyone who has queries about statistical concepts that are used in the public discourse.

The methodology for analyzing excess mortality data

How we analyzed Greece’s excess mortality rate for the year 2020.

The situation in schools as a core issue

Representative of Betsy Ladyzhets’ work at the CDD are two recent posts titled “Privacy-first from the start: the backstory behind your exposure notification app” and “CDC says 80% of teachers and childcare workers are vaccinated, fails to provide more specifics“, regarding mobile device-based close contact case tracking apps and the failure to provide data on the vaccination status of teachers and childcare workers respectively.

In fact, data on COVID-19 in schools is one of the main categories in Ladyzhets’ self-publication (see the “K-12” section of the website –an American expression denoting the range of years from kindergarten to 12th grade). “I have made K-12 data a priority in the CDD because I believe it is one of the biggest data gaps in U.S. COVID data. Most notably, there is no official, federal dataset on COVID cases in K-12 schools. The Trump administration simply failed to take responsibility for this area of data collection. Some journalists and researchers (myself included) thought that the Biden administration might step up when he took office; and the Department of Education is releasing monthly surveys now on school attendance and opening models, but there’s still no data on COVID cases, tests, or enrollment in schools. And, while most states report data in this area, the quality varies widely and is overall pretty poor, as you can see on the CDD K-12 data annotations page. Fewer than five states report enrollment numbers (how many kids are attending school in-person), and only one state, New York, reports testing numbers. Without such data, it’s difficult to contextualize the case counts that are more commonly reported”, explains Betsy Ladyzhets and goes on to add: “Besides the obvious failure of the government to meet its responsibilities here, the lack of standardized, useful K-12 school data has contributed to a massive debate in the U.S. over whether schools can be safely opened for in-person instruction during the pandemic”.

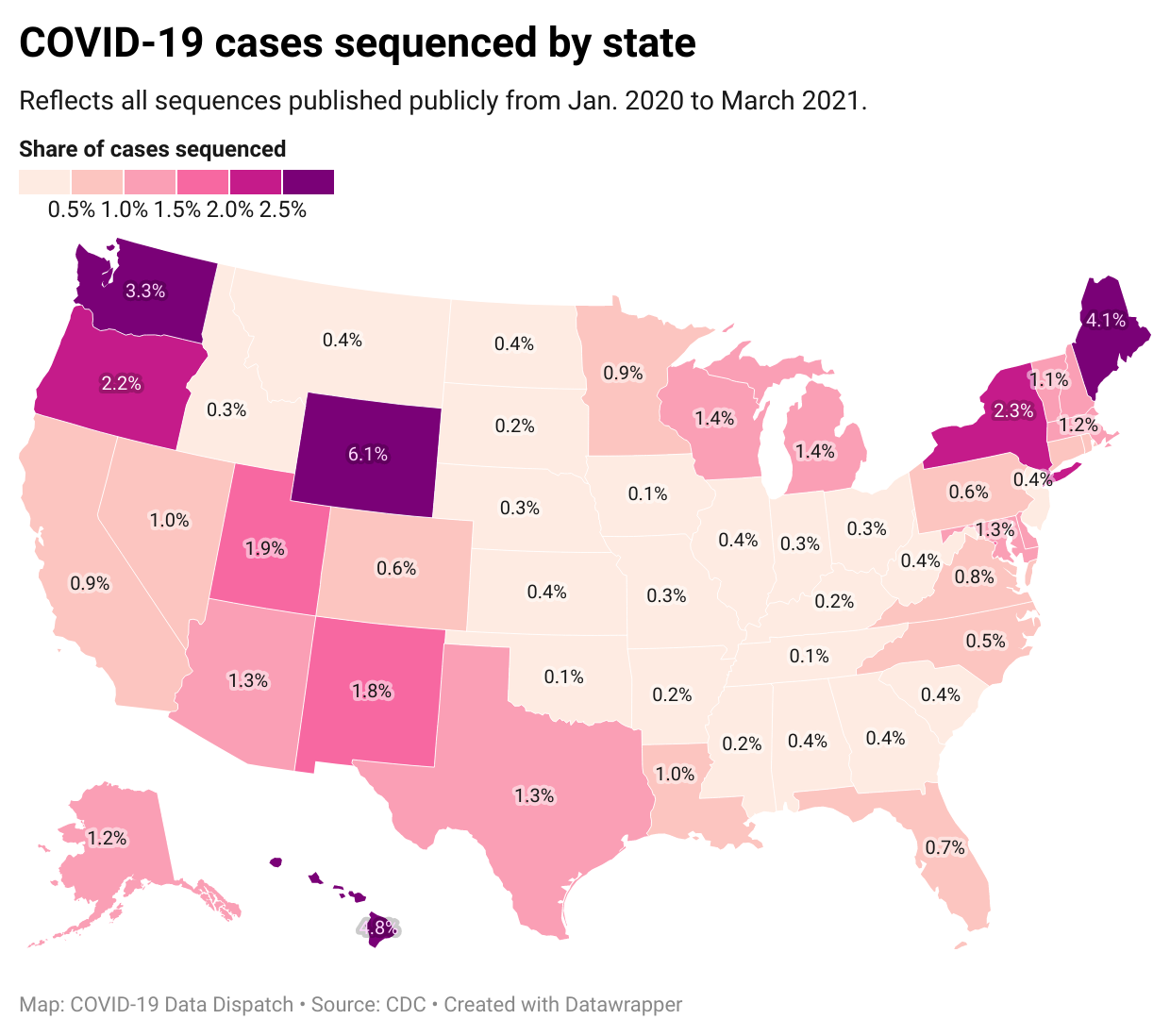

American COVID-19 data

Asked about the quality of pandemic data in the US at both federal and state level, Ladyzhets tells us that what she perceives as one of the biggest problems is the fact that “in this country, we are not actually dealing with one singular, standardized system. We’re instead dealing with 56 smaller systems (50 states and 6 territories). Each system has its own rules, its own reporting practices, its own data definitions. All the systems have been underfunded for decades and were given very little guidance from the federal government, basically until Biden took office this past January. You really see this lack of leadership and consistency everywhere, from the fact that some states reported their tests in units of specimens while others reported in units of people, to the fact that two states are still not reporting race and ethnicity data for their vaccinated residents, even now, four months into the vaccination effort”.

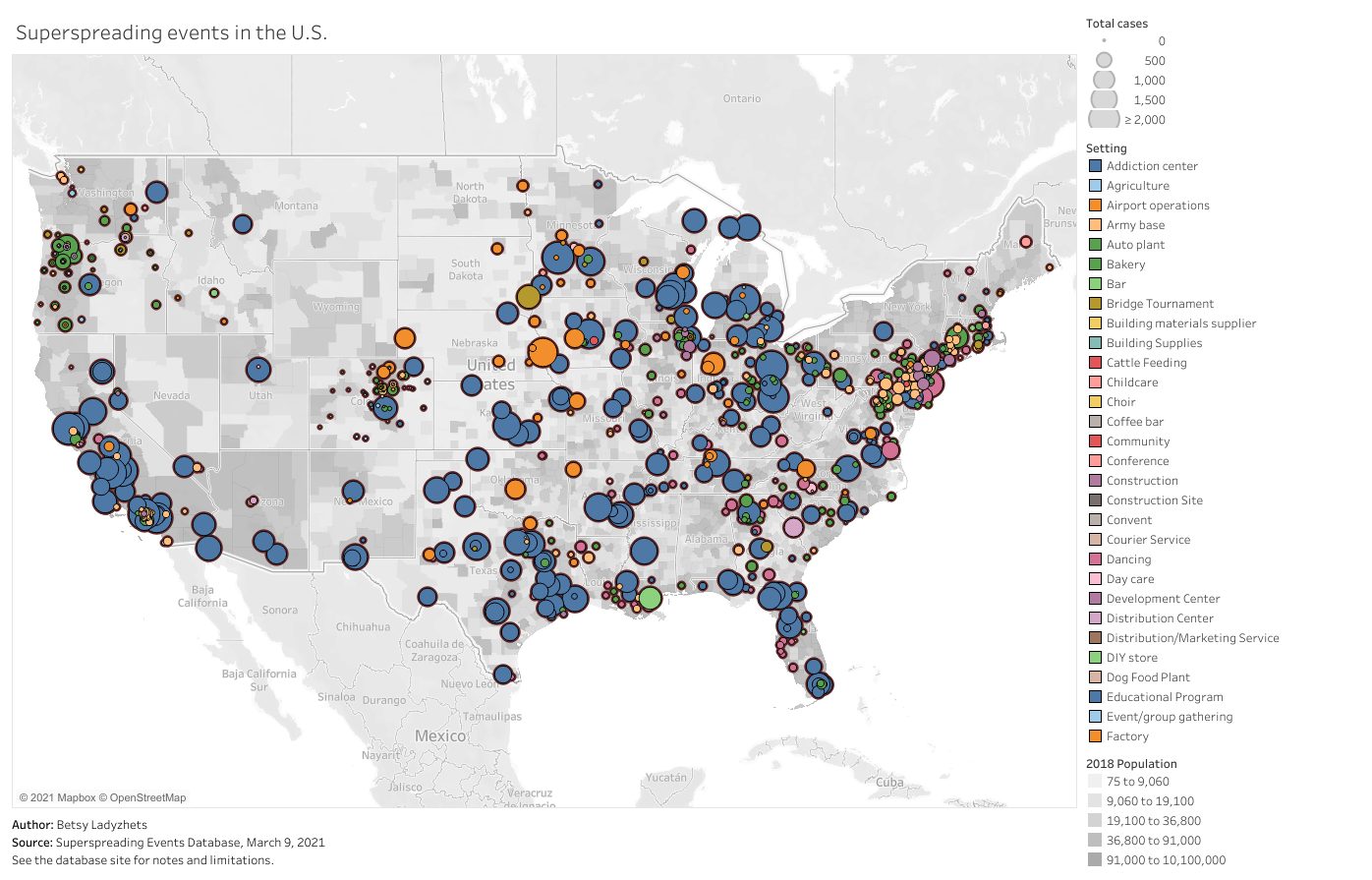

Regarding improvements in the field during the pandemic, as well as positive milestones in terms of the availability of official data, Ladyzhets says, “we saw many noteworthy milestones in December and January”, citing the availability of an open, HHS facility-level hospitalization dataset (updated weekly) and the Community Profile Report available in .pdf and .xlsx format, which include data on key pandemic variables at the federal and state levels as indicative examples.

Community building, career advancement and plans for the future

With the CDD, Betsy Ladyzhets has managed to build a community of about 600 loyal readers –”this includes a couple hundred journalists and communicators, a smaller number of scientists and health professionals, and many more lay readers who simply find the work interesting”. Of this readership, some use the sources or topics the CDD highlights to assist them in their work and others simply get informed about the pandemic, with the CDD acting as a tool for understanding the data.

In order to sustain the venture, Betsy Ladyzhets has been using the Ko-fi app, which allows users to “tip” her (a sum of money of their choice), and she also launched a monthly membership model last January ($10 or $2 package): subscribers enjoy some additional benefits, such as access to a Slack server of COVID-19 reporters/communicators, exclusive cleaned datasets to use, and the ability to shape the material covered by the CDD by communicating their own priorities. The website “is not yet financially sustainable: current membership fees are enough to compensate my intern and cover a small fraction of the tech I use to host the publication, but I would need to do a much bigger push for memberships to fully cover my costs or even start to cover the time I put into producing issues”. This was, after all, one of the reasons she recently quit her day job (so as to fully devote herself to the CDD and to freelance collaborations), “in order to do that bigger push, in combination with more services and engagement options for those who become members. I’m also seeking partnerships with and grants from other organizations that may be able to support the CDD”.

Another factor that probably motivated Betsy Ladyzhets to devote herself exclusively to the CDD and to her freelancing was the boost that the CDD seems to have given to her career: “The CDD enabled me to really make COVID data my beat. I was already going in that direction in the first half of 2020 due to my day job and the COVID Tracking Project, but that extra pressure that the CDD’s structure gave me –forcing myself to come up with something useful and interesting to cover each week– pushed me to explore new datasets and dig into specific topics that I wouldn’t otherwise be covering”, she mentions, among other things, and continues: “the CDD is valuable as a career builder. I was selected for the first cohort of a new graduate program at the City University of New York’s Journalism School, I got to lead the “Lessons learned from a year of working with COVID-19 data” panel at the NICAR 2021 conference, and I have had other professional opportunities arise due to my work on the CDD. It’s helped me build a reputation as someone who is passionate and driven in her coverage of COVID data, and who has gained expertise simply by doing the work every week”.

Asked whether she is planning to keep the CDD going beyond the pandemic, Betsy Ladyzhets excitedly confirmed that yes, of course she is, and added: “even after it becomes less of a concern in the U.S., I envision my work shifting to have a more global focus –much of the world won’t get vaccinated until 2022, after all– alongside reporting on the aftermaths of the pandemic here. Thanks to climate change and the increasing likelihood of all kinds of natural disasters, I know that COVID-19 will likely not be the only pandemic in my lifetime”.

Translation: Anatoli Stavroulopoulou