Ann Hermes has spent six years photographing the fading world of U.S. local news, capturing the humor and humanity of newsroom life alongside the melancholy of an industry in retreat. She spoke with iMEdD about the state of local journalism today — and what it might become tomorrow.

Photographs: Courtesy of Ann Hermes

Featured image: Broken newspaper bins sit in the parking lot of The Auburn Journal on July 10, 2023 in Auburn, California.

The newsroom is nearly empty. The outlines of desks are still visible in the carpet, faint impressions of a busier past. Fluorescent lights hum overhead. Since 2018, Ann Hermes has been visiting local newsrooms all over the United States with her camera and studio lights. Her mission? To document unguarded moments of a news business that is quietly fading away.

The State of Local News Report by the Medill Local News Initiative, a study that has tracked local outlets in the U.S. for a decade, found that nearly 40 percent of local newspapers have disappeared since 2015. In 2025 alone, more than 130 newspapers closed, matching the pace of 2024 and leaving roughly 50 million Americans with little or no reliable source of local reporting.

The idea for her photo and video series, Local Newsrooms, started in 2016, when Hermes began to hear repeatedly a familiar accusation: that journalists, taken as a class, were elitists, detached from the communities they claimed to serve. “If you’ve been in the local newsroom, you can see that it is very far from the truth,” she said to iMEdD, speaking from her home in Brooklyn, New York.

After visiting the St. Louis Post-Dispatch, a local newsroom that in 2015 won a Pulitzer Prize in Breaking News Photography for its visual coverage of Ferguson, Hermes kick-started six years of self-funded trips to more than 50 local newsrooms “from Florida to Alaska and everywhere in between”, often combined with other photography assignments.

She has focused particularly on newsrooms near or adjacent to news deserts, which she describes as “the last foothold for news coverage in these areas.” Now, she plans to take this work to the areas where it could have the biggest impact, and to show it in local libraries, hoping it will encourage communities to support trusted local news. “I think a lot has been written about the demise of local news, but people who live in these communities often aren’t aware of it.”

Humor and survival

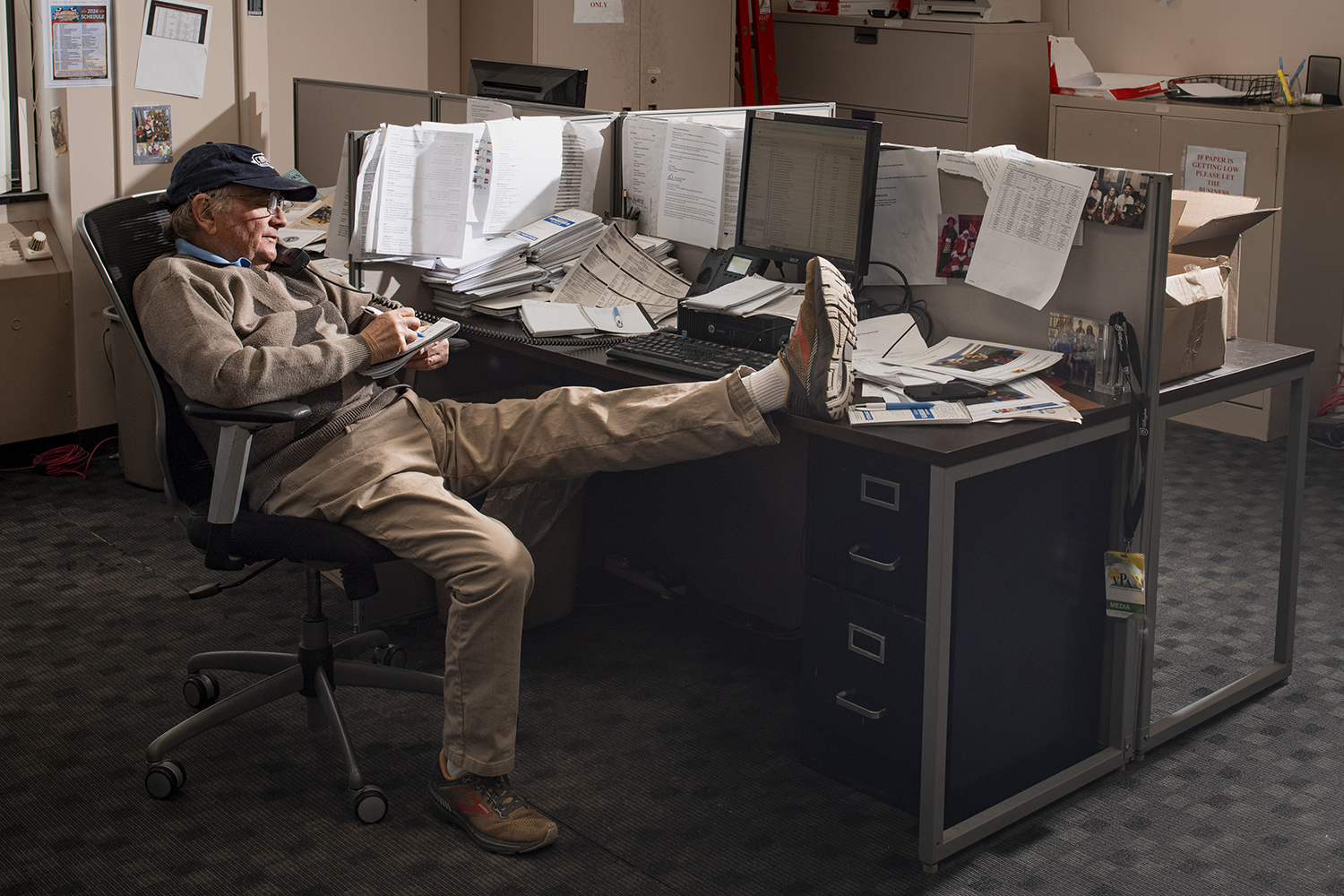

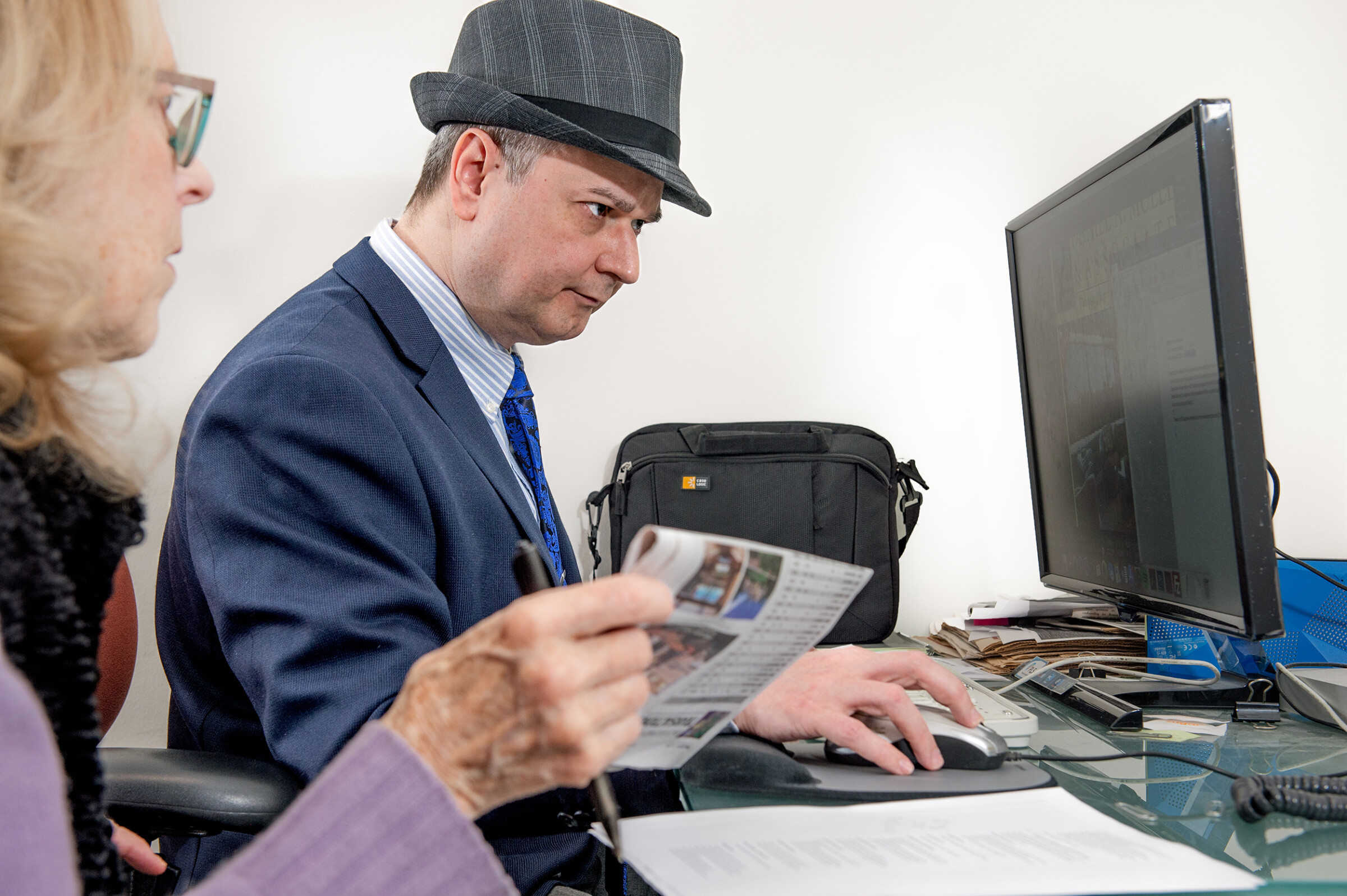

Every photoshoot grows out of shoe-leather reporting, meticulous research, and long hours of preparation. Hermes conducts pre-interviews with managing editors, lingers in empty newsrooms, and waits for the quiet, fleeting moments that reveal the rhythm of daily reporting. To bring a sense of drama to what is otherwise a still, understated environment, she sets up her studio lights, crafting cinematic scenes that feel both orchestrated and undeniably real.

A photographer with more than fifteen years of experience in local and national media, she knew what to look for. “You notice some of the same things in every local newsroom, and they’re often pretty funny,” she said. “A printout of the First Amendment, a stapler labeled for the photo desk, police scanners, and history books of the town. There are just certain commonalities, especially in newsrooms that have been around for a long time.”

Yet beneath the humor, there is a deep sense of history that Hermes can’t ignore.

You notice some of the same things in every local newsroom: a printout of the First Amendment, a stapler labeled for the photo desk, history books of the town […] I look at these dilapidated rooms and think: ‘this is an entire town’s history that exists only here’.

Ann Hermes, photographer

“A lot of these places have existed for over 100 years,” she said. “They’ve been in their buildings for 50, 60, 70 years in some cases. And I find it fascinating that… these legacy institutions are just now facing threats of closure after having existed for this long.”

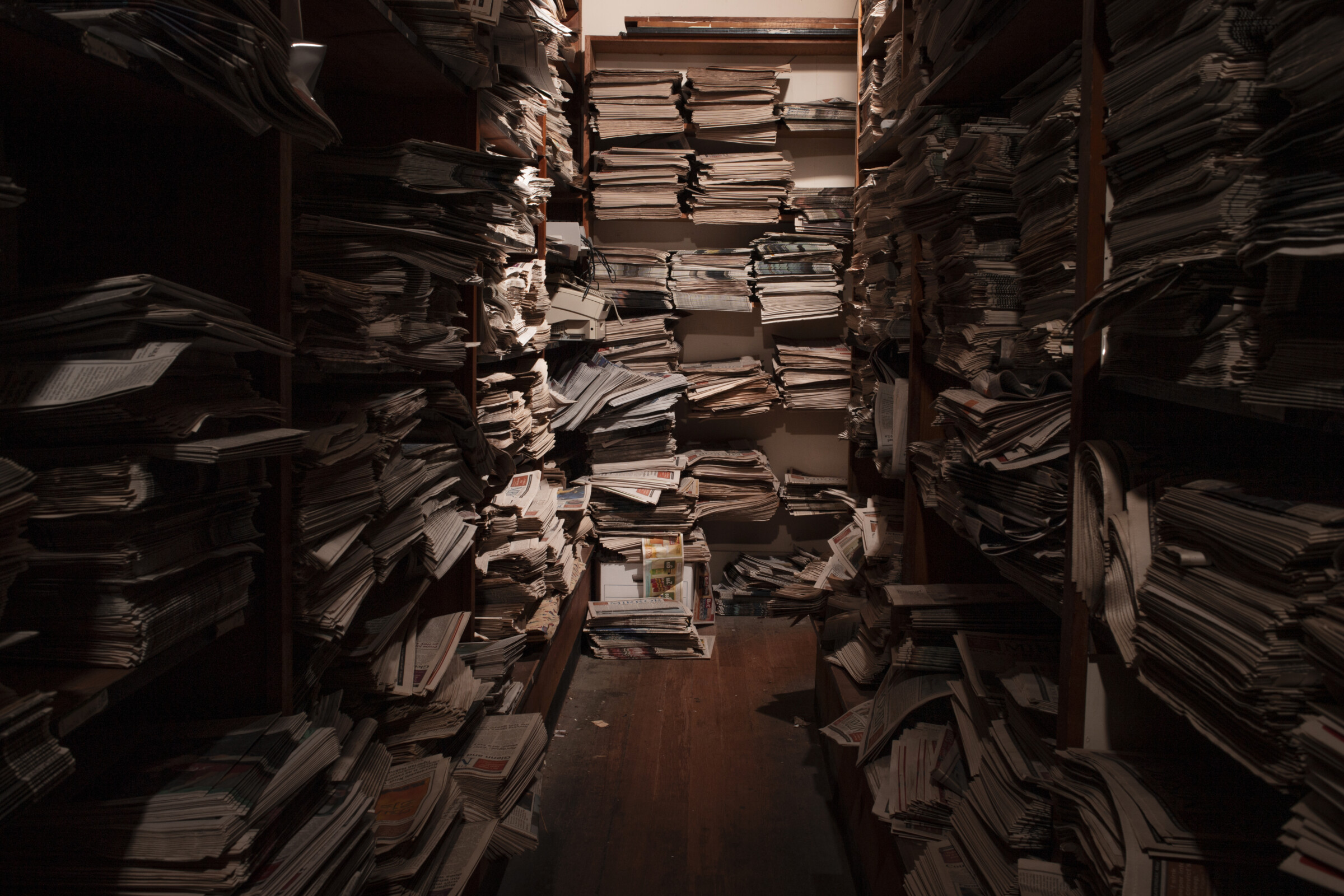

In every newspaper newsroom, she visits “the morgue” — the archive of old issues, photographs, and clippings — usually tucked away in a back corner, a cellar, a basement, or a closet.

“I look at these dilapidated rooms with collections of papers slowly disintegrating and think: ‘this is an entire town’s history that exists only here’. I find that fascinating, and it’s something I want to capture, because I don’t think newspaper morgues will exist within my lifetime. It’s part of the story.”

Candid moments captured across the US

I wanted to capture a lot of these people in spaces before they either make a full transition to digital or, in many cases, sadly, end up closing entirely.

Ann Hermes, photographer

How local newspapers navigate change

Amid the sweeping changes reshaping local journalism, Hermes set out to document the people and spaces most at risk. “I wanted to capture a lot of these people in spaces before they either make a full transition to digital or, in many cases, sadly, end up closing entirely,” she said. Her attention turned particularly to family-owned papers, where she found a rare openness. “When I reached out, they would just open the doors: ‘When do you want to come? What do you want to see? Attend our staff meeting—whatever you like.’ That kind of access is what makes these photos possible.”

It was that access that allowed Hermes to capture moments that feel both ordinary and intimate. “These are some of the best subjects a photographer could want: they don’t overact, they don’t underact, and I don’t have to explain what I’m doing. They just let me hang out and capture candid moments in the newsroom.” The images, she noted, reflect a reality that stretches far beyond a single office. “These scenes happen across many different newsrooms. I find them funny and lovable, and I hope that comes across in the images.”

Hermes has also found that local newsrooms often navigate nuance that gets lost at the national level. “There’s a lot of nuance that’s being lost in the polarization on the national level that’s still occurring on the local level,” she said.

She recalled a publisher in California who, frustrated by angry letters, decided to refer to Trump simply as “the president” in headlines, without altering coverage otherwise. “He said that cut the number of angry letters in a really significant way,” Hermes noted. “If people could engage with their newsroom, they would find that these are the people who have the same concerns as they do because they live in the same community.”

She admires how local journalists find small, conscientious ways to reach their readers while remaining factual — “things like that…are really amazing and lovely and are happening on a local level in ways that are often overlooked.”

Having an impact

The Medill study also found that Employment in local news has dropped at a staggering rate since 2005. In 39 US states, fewer than 1,000 local journalists remain today.

Last November, Hermes’ work was featured at The New Yorker. The piece put her work under the spotlight and prompted many readers to reach out directly to her.

“I’ve gotten a lot of letters from people who used to work in local newsrooms,” Hermes said. “A lot of them have worked in local news, so there’s a nostalgia aspect, and I do lean into that. But there’s another part I want to highlight — helping with the survival of local news. It’s an awareness project.”

This article is published by iMEdD and is made available under a Creative Commons license (CC BY-NC 4.0). This license does not apply to the images by Ann Hermes included in this publication, which are published courtesy of Ann Hermes for the purposes of this piece. Any other use of these images by third parties requires prior communication with the photographer for her permission.