Can a cartoon be “born” from an algorithm? If so, what does this mean for the future of satire and commentary? An AI researcher and four cartoonists speak to iMEdD. The latter explain why, after experimenting, they chose to leave it out of the picture – for now.

Investigating Artificial Intelligence: What lies beyond the algorithm

Artificial Intelligence has become an integral part of our daily lives — but the real cost is often borne by others. At the Dataharvest conference, journalists presented their investigations and shared tips on how to dig deeper into this technology.

In March 2025, OpenAI announced an upgraded version of ChatGPT (GPT-4.0) with the ability to generate images and comic strips. For the first time, ordinary users could easily create “satirical images” of politicians.

In its promotional video on YouTube, the company said that ChatGPT was “imbued with the idea of an artist in conversation with you.”

Within days, social media feeds were flooded with AI-generated images mimicking the style of the iconic Japanese animation studio, Studio Ghibli. The so-called “Ghibli effect” sent ChatGPT’s weekly active users soaring, surpassing 150 million in record time.

But who is the real artist when a cartoon emerges from a “dialogue” with a machine? What questions does its use raise? iMEdD spoke with cartoonists exploring AI tools to better understand what machine-generated images mean for the future of their work.

Technological leaps in AI image generation

The first tools based on text-to-image neural networks appeared in 2021. Since then, they have become extremely popular, both among the general public and professionals.

The fact that we have reached the point where we can create Studio Ghibli-style images using tools such as ChatGPT “was a series of many technological leaps,” says Ioannis Siglidis, engineer and postdoctoral researcher at the Pioneer Center for AI in Copenhagen, tells iMEdD.

In 2019, together with comic artist Ilan Manouach, they created an algorithm based on artificial intelligence models that published “synthetic” cartoons every day for three years (2020-2023) on the Neural Yorker account on X (formerly Twitter). “[At the time], we were inspired by the future we saw sketched out by these early models. What we couldn’t predict was the speed of their progress and their rise in popularity,” says Siglidis.

Just six years ago, the capabilities of image generation models, known as GANs (Generative Adversarial Networks), were still very limited. Many leaps have been made since then, resulting in the ease of prompting that we see today.

GPT-4o has revolutionized the field. It does not just apply filters to the image. It can identify its main objects and reconstructs it. “Basically, the pixel soup has been turned into ramen noodles”.

“First, the diffusion models managed to make progress towards what we now call compositional generalization, where they could compose images with objects that had never existed or been seen together in the same image, such as a horse on the moon,” says Siglidis.

Then, the way they respond to user commands (prompts) was improved. GPT-4o – which now produces images like those in the style of Studio Ghibli – has revolutionized the field. It doesn’t just apply filters to the image. It can identify the main characters and “understand” what the main objects in the image are in order to reconstruct it.

“Basically, the pixel soup was made from mush to ramen,” he says, making a triple reference to Studio Ghibli; to the metaphysics of Ludwig Wittgenstein, the philosopher of language and mathematics, where the external world is continuous and lacks clear categories; and to the phenomenology of computer vision. “All images in a genetic model start out as noise, and genetic models learn how to form structure and meaning within that noise,” he notes. “Soup” means that the models do not need to understand very well what the soup-like image contains. In contrast, “ramen” means that the algorithm creates very distinct objects—just like a soba ramen soup—after first reaching the so-called “decomposition” of the data.

Is cartooning threatened by AI?

In December 2022, the Association of American Editorial Cartoonists (AAEC) prohibited its members from submitting AI-generated images for its awards.

“As far as editorial cartooning is concerned, no. [AI] is not a threat so far,” says KAK (Patrick Lamassoure), president of the cartoonists’ network Cartooning for Peace since 2019, speaking to iMEdD.

Having experimented with various AI image-generation tools for his cartoons in L’Opinion and Franc-Tireur, he concluded that artificial intelligence cannot replace the cartoonist.

“When you want to create a good editorial cartoon, it’s usually about something that just happened. In most cases, AI isn’t aware of it,” he says. Even if it manages to “catch up with” the news, he adds, artificial intelligence would still need to come up with a good idea for the cartoon and, of course, add a little humour.

A typical example of AI’s limitations was a recent cartoon he generated using Adobe Firefly, another image-generation tool that creates pictures from text prompts. He asked for a cartoon of Donald Trump and his proposal for the US to take control of the Gaza Strip. The resulting image, he says, was generic and only inspired him to draw the cartoon himself from scratch.

What’s threatening cartooning, he notes, is the decline in newspaper circulation. “We have to find a new business model. (…) Combine that with the global trend of people reading [the news] less and listening to or watching it more.”

Plagiarism… with one prompt

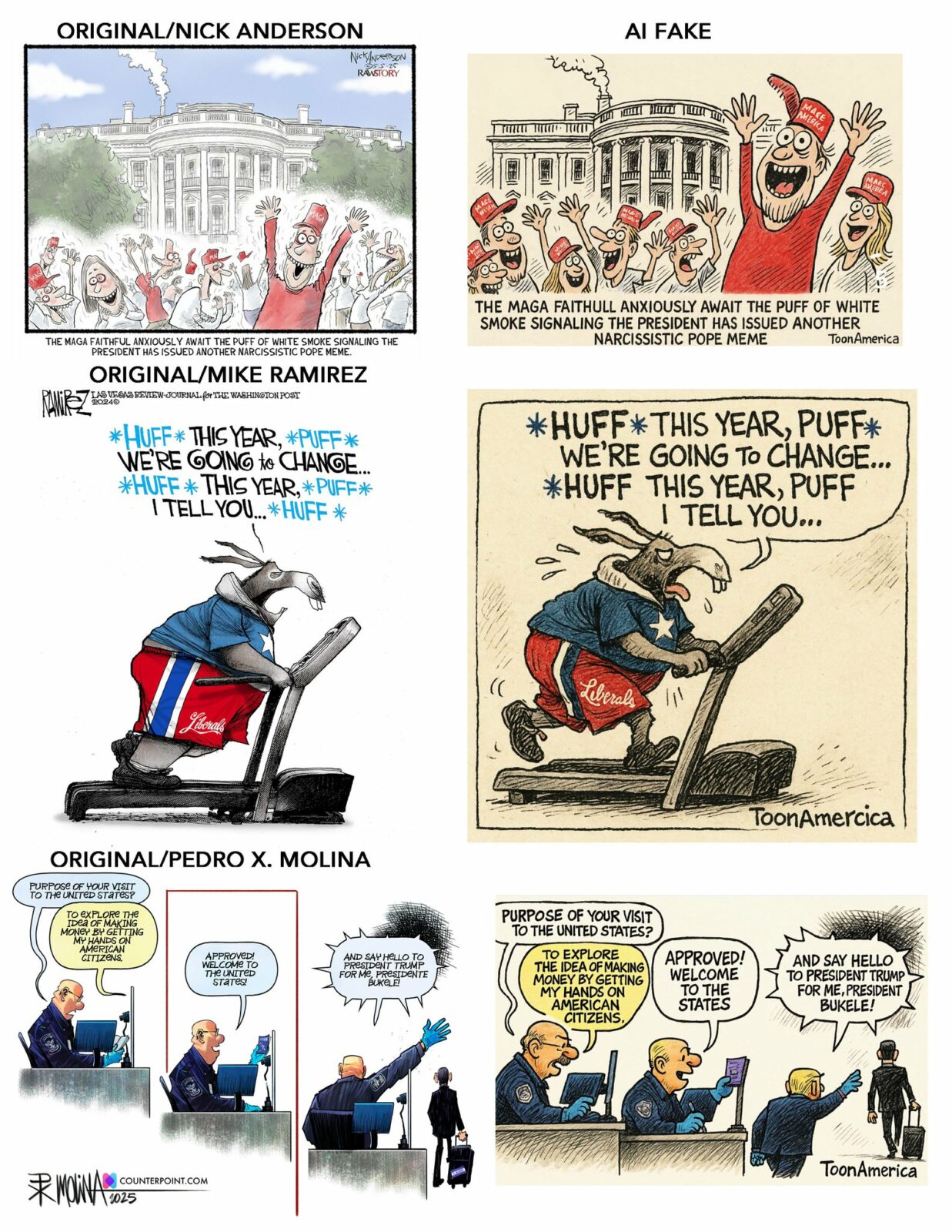

Last May, Nicaraguan political cartoonist Pedro X. Molina revealed on Facebook that AI tools had reproduced his cartoons, as well as those of his colleagues.

Now living in exile in the United States, Molina left Nicaragua in 2018 because of the Ortega regime. Nevertheless, he continues to work as a cartoonist and illustrator, contributing to the independent Spanish-language newspaper Confidencial.digital, the platform Tinyview.com, and the Tribune Content Agency in English.

His social media post highlighted another threat: the unintentional or deliberate use of AI-generated recreations of cartoons without the creators’ permission.

“They were using AI to recreate those cartoons in another style,” Molina told iMEdD. “This cheapens the work, but it also leaves real creators without the incentive, the space, or the opportunity to keep doing what they do and to make a living from it.”

Molina’s cartoons had been slightly modified using AI tools, but carried a different signature and were posted by the accounts “AmeriSatire” and “ToonAmerica” on TikTok and YouTube.

According to Molina, the creators jointly submitted a request to social media platforms to take down the altered cartoons, which were soon removed. However, they are now considering legal action.

I’ve used AI to generate images, to see how it works. (…) But especially for my own designs, I don’t want to just ask it, ‘Give me a funny idea,’ because then you enter a process where you essentially surrender to a machine what makes you human, what makes you special

Antonis Vavagiannis, editorial cartoonist at News247

The creators’ concerns about plagiarism are nothing new.

From the very first days of ChatGPT’s new image-generation capabilities, Brad Lightcap, OpenAI’s chief operating officer, told the Wall Street Journal: “We’re respecting of the artists’ rights in terms of how we do the output, and we have policies in place that prevent us from generating images that directly mimic any living artists’ work.”

Among the creators wary of using artificial intelligence due to plagiarism risks is Antonis Vavagiannis, a cartoonist at News247 and creator of the popular comic book series Kourafelkythra, who has more than 80,000 followers on Instagram.

“I’ve used AI to generate images to see how it works. I’ve used it to search for information. But especially for my designs, I don’t want to just ask it, ‘Give me a funny idea,’ because then you enter a process where you essentially surrender to a machine what makes you human, what makes you special,” he tells iMEdD. “I’ve been doing this my whole life: finding ideas, creating images. If I’m going to hand that over to AI, then it’s like losing a big part of the joy of life, which for me is creation and creativity.”

Copyright: the limits of “synthetic” creation

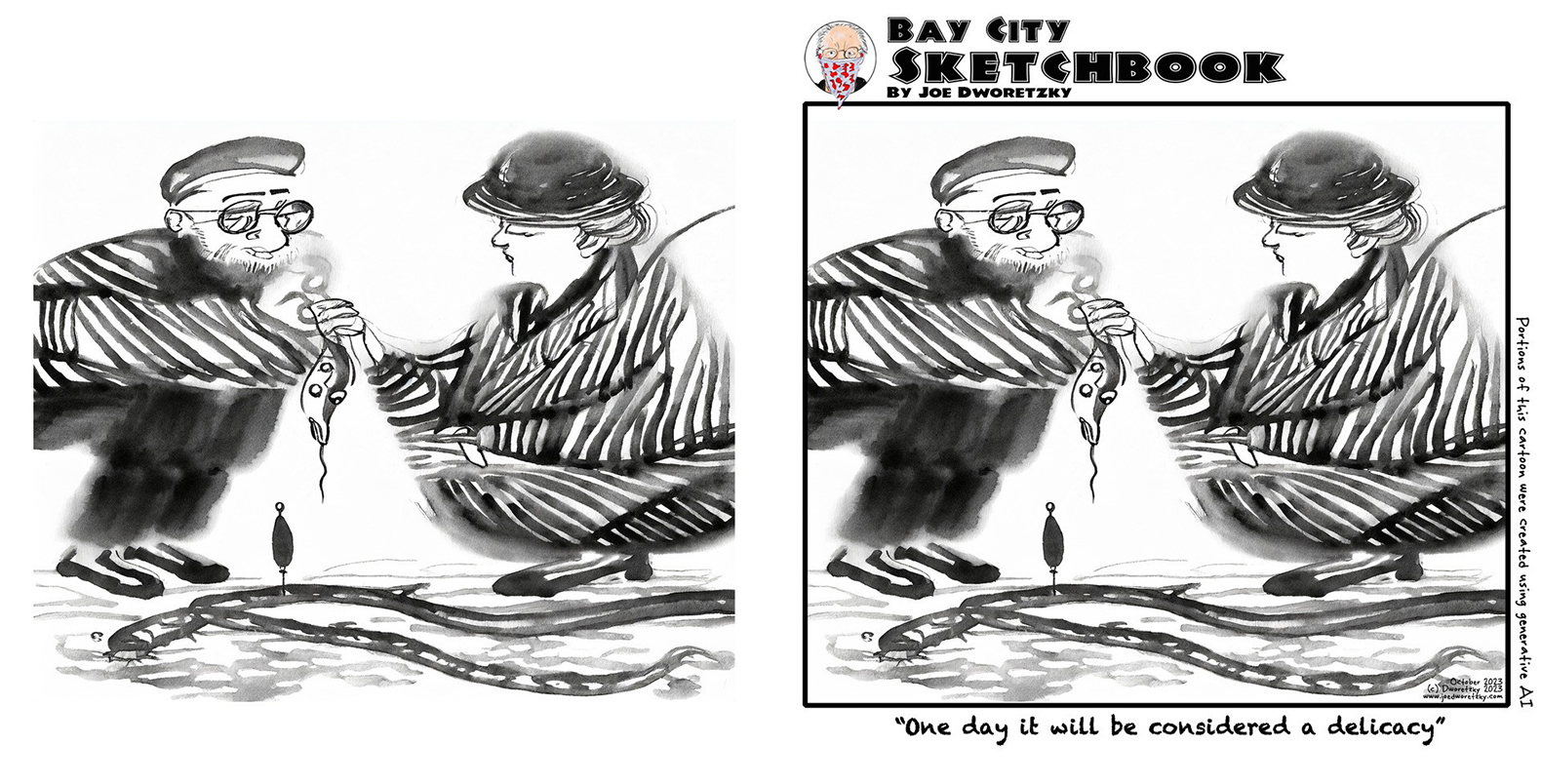

Joe Dworetzky, a cartoonist for the local American outlet Bay City News, moved into investigative journalism, court reporting, and cartooning after a 35-year career as a lawyer.

For the first four years, he mostly created cartoons on social issues such as homelessness and covered the tech industry in San Francisco. In 2024, while covering the Democratic and Republican election campaigns, he began including political cartoons in his articles.

Before long, he experimented with all the available AI image-generation tools, mainly as inspiration for his cartoons. He uploaded 40 to 50 of his drawings in the same style to Leonardo AI and tested different prompts, making several adjustments. With DALL-E, he created a series of cartoons to accompany his reporting on the legal dispute between Elon Musk and Sam Altman, which were marked for readers as AI-generated.

“I was stunned at how quick, convenient – and, I think, really good – some of the stuff that I was getting out of the different platforms was,” he tells iMEdD.

At the same time, he felt that the output did not fully represent his work. “In one sense, it feels a little bit like it’s not really my work. It’s kind of passing off somebody else’s work. I try to be clean when I use AI,” he says.

As he explains, there are currently court cases – such as the one filed by New York Times – that are expected to set a legal precedent regarding copyright and the use of media content for the “training” of artificial intelligence.

Noting that he is simply sharing his opinion, he says: “Τhere’s two separate issues. One is whether taking the original data and using it to feed the AI – the training data – whether that itself is a copyright issue. And then second, whether a work that’s generated by the AI that’s in the style of somebody else’s work can also be a copyright violation. And I think those are two different questions.”

He adds that the second case is more complex: “What comes out… I think that’s gonna be a pretty tough copyright case. As I understand the way AI works, it doesn’t generate cartoons by copying what’s there. It’s more like it looks at what’s there and it learns what the principle of cartooning is, and then it replicates that in its own way.”

Cartoons are not memes

Creating cartoons, even with artificial intelligence tools, is not a simple or automatic process. It’s the result of a multistep process that a cartoonist must follow: researching current events, composing the image, and deciding on the focus and the humour.

Journalists and cartoonists who sign their work, Pedro Molina tells iMEdD, play a crucial role in making sense of today’s often chaotic reality, as cartoons distill and analyse current events with humour.

He designs at least eleven cartoons a week, each of which requires hours of research, experimentation, and design to complete.

“Young people come to me and say, ‘You draw memes’ (…) They just don’t know the difference. That’s why we need to educate people — help them understand what the difference is,” he says.

“We’re the fact-checkers. (…) Because if you can’t trust anyone, then you’re forced to believe anything — or nothing at all. And if nothing is real, then nothing is worth fighting for.”

Translation: Anatoli Stavroulopoulou