We spoke with the journalists behind the award-winning cross-border investigation “Τhe Shadow Fleet Secrets,” which revealed how hundreds of oil tankers operated by Western companies ended up carrying Russian crude oil.

Featured Image: Follow the Money

In the months following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, a quiet trade spread through shipyards and broker offices across Europe. Aging oil tankers, once operated by European companies, were changing hands at extraordinary prices. To the casual eye, it looked like business as usual. But to a team of journalists, it pointed to something larger: the creation of what would become known as the “shadow fleet”; hundreds of vessels repurposed to transfer Russian oil beyond the reach of Western sanctions.

Follow the Money’s investigation into Russia’s shadow fleet received the 2025 Daphne Caruana Galizia Prize for Journalism

The investigation “The Secrets of the Shadow Fleet”, coordinated by Follow the Money in collaboration with 13 media outlets from across Europe – two of them Greek – was honoured with a symbolic award for press freedom.

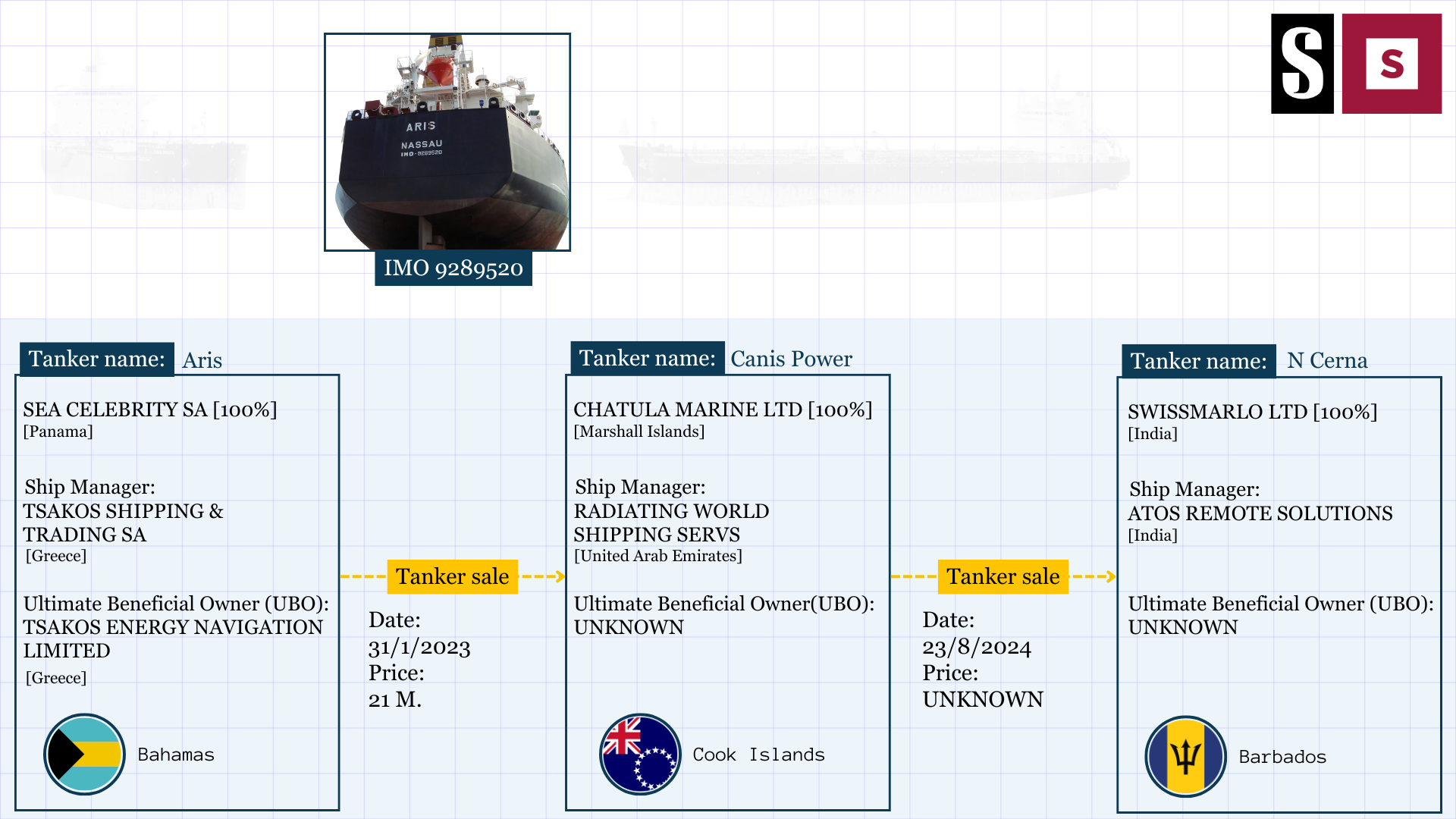

More than two hundred ships, many of which had once sailed under European flags, were soon registered in distant jurisdictions and reflagged under “tax haven” nations such as the Marshall Islands and the Seychelles, continuing to transport Russian crude oil. Among them were vessels previously owned by Greek, British, and German companies, sold for vast sums to single-purpose companies set up to act as intermediaries in subsequent transactions.

“The oil tankers didn’t fall from the sky,” said Jesse Pinster, an investigative journalist at Follow the Money, which led the cross-border project The Shadow Fleet Secrets, winner of the 2025 Daphne Caruana Galizia Prize for Journalism. “Someone has to solve it. We just needed to find out who and how,” he added.

Inside the investigation

The idea for the investigation, as Pinster recalled, arose from a conversation with a ship broker in Rotterdam and a discovery on Hellenic Shipping News, a website hosting weekly broker reports in PDF format. Those reports listed ship names, occasional sale prices, and sometimes buyer details.

“We already had a list of vessels in the shadow fleet. Now we had a list with ship names in broker reports. Connecting all of those was the starting point,” he explained.

The project began with data from the Kiev School of Economics Institute, which had compiled a list of tankers with opaque ownership and no Western spill insurance. Building on that list, Follow the Money established a collaborative network bringing together 13 international media outlets and 40 journalists from nine countries—including Solomon and Inside Story from Greece—coordinated through Signal, cloud-based platforms, and online meetings. Together, they mapped the global trail of ship sales, shell companies, and intermediaries that continued to drive Russia’s oil exports.

The collaboration developed organically along the way, as Follow the Money was conducting its investigation “The North Sea Investigations”. “We were already working with media outlets from countries surrounding the North Sea,” explained Birte Schohaus, an investigative journalist at Follow the Money. “We knew this investigation would need people from countries who either have a big shipping industry or have big ports. That’s why partners from Greece, Germany, Belgium, Norway, and other countries took part. “We started small and expanded as we found more vessels linked to new countries,” she added.

The consortium used a mix of data-driven analysis and “old-fashioned” reporting to verify each vessel’s identity, ownership, and sales timeline. They pulled together information from a range of sources: the Kyiv School of Economics Institute’s shadow fleet list as a starting point; Equasis for historical records on vessels, owners, and managers; Global Fishing Watch (GFW) for behavioral data such as port calls and AIS signal gaps; and IHS Markit for authoritative information on ships and their ultimate owners. Geospatial data was also used to detect suspicious, prolonged rendezvous between vessels. All datasets were cleaned and standardized using Python, then merged into a PostgreSQL database that formed the backbone of the investigative queries and network analysis, following a published and openly accessible methodology. Still, as Pinster and Schohaus pointed out, the technical work was more painstaking than high-tech, and the project involved “a lot of manual labor,” as Schohaus put it.

Unravelling the thread from Piraeus: The Greek chapter

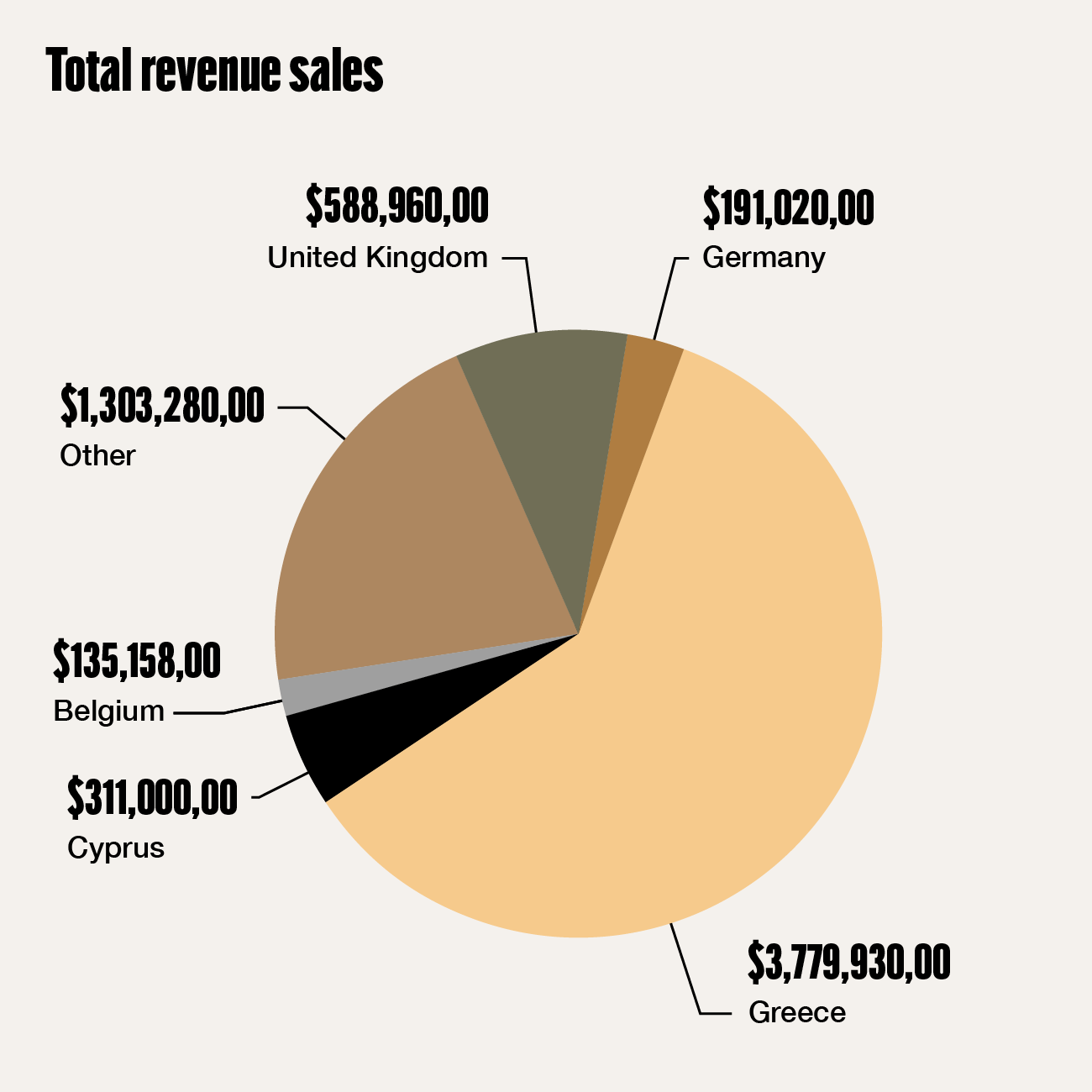

The Greek shipping sector—the largest in the world in terms of vessel ownership—played a decisive role. According to the investigation, Greek shipowners alone sold more than 3.7 billion dollars worth of vessels to the shadow fleet, out of a total of 6.3 billion. When the Greek media partners Solomon and inside story joined the project in late 2024, most of the core data was already in place and it showed that 127 of the 230 vessels had once belonged to Greek companies. “Suddenly we found ourselves with the biggest share of the work and the least amount of time,” said Danai Maragoudaki, investigative reporter at Solomon.

Together with fellow investigative journalist Eliza Triantafillou from inside story, they began meticulously cross-checking every element of the dataset: who the recorded owners were, whether the listed companies were indeed based in Piraeus, and through which pathways each vessel had changed hands. “It wasn’t enough for us to take something for granted just because everyone said so. We started by verifying everything from scratch,” Danai explains. “It was detective work; we had to prove ownership through documentation,” she stresses.

The Greek investigative team combined Lloyd’s List Intelligence criteria with the standards of the Kyiv School of Economics Institute and came up with 100 mutual vessels to be assessed.

Their verification work relied on shipping registries and databases such as IHS and Equasis. In some cases, the team identified intermediary companies that did not appear in the original dataset. “We initially thought one vessel had been sold directly to a Russian company,” notes Maragoudaki, “but later we found a broker company acting between the two.”

The two journalists also contacted 51 shipping companies and their owners, sending letters requesting clarification: first, confirmation that the companies recorded (and their connections to specific vessels) were accurate; and second, comments on why certain vessels appeared on certain lists. “Around ten or eleven replied,” says Triantafillou—most of them claiming full compliance with European and international law. “Three or four of those who did respond used a more threatening tone,” adds Maragoudaki, referring to warnings that publication would constitute defamation.

What counts as legal – Understanding the sanctions

As the journalists examined corporate records and sale prices, another question emerged: were these sales illegal?

At that time, selling ships to Russian interests was not explicitly prohibited. The sanctions targeted the trade of Russian oil, not the sale of vessels. “We had to understand the sanctions framework,” explains Danai Maragoudaki. “There was a learning curve,” adds Eliza Triantafillou.

The two journalists identified three critical periods:

- Before the price cap, which came into force in December 2022 —after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, the G7 and the EU imposed a ceiling on the price of Russian oil and its derivatives, prohibiting vessels linked to their jurisdictions from transporting oil sold above that limit, in an effort to reduce Russian revenues without disrupting global supply.

- Between the implementation of the price cap and the EU’s formal ban on tanker sales, introduced in December 2023.

- After the ban, the rules became significantly stricter.

By the time direct sale restrictions took effect, most vessels had already changed hands.

“The boom had already happened,” notes Triantafillou. “Shipowners had cashed out, demand had dropped, and the ecosystem of intermediary companies was already in place so that everyone would be covered.”

During our conversation, they mentioned a discussion they had with Michelle Wiese Bockmann, analyst at Lloyd’s List Intelligence, who illustrated the situation as follows: “If you have an old car you don’t want anymore and it’s worth 2,000 dollars, but someone comes and offers you 4,000 dollars for it, you won’t just sell them that one —you’ll sell them any car you can find. That’s essentially what happened with the shadow fleet.”

“The sales were technically legal,” Maragoudaki acknowledges, “but were they ethical?” As she put it: “You couldn’t just write ‘bad shipowners’. That would be superficial, populist, and would explain nothing. So we started digging deeper, speaking with sources across Europe and in Greece to really understand how the sanctions worked.”

Unpacking the story: Brazil’s hidden shark meat trade

Mongabay journalists Carla Mendes and Philip Jacobson reveal that toxic shark meat is being served in schools, hospitals, and prisons.

Connecting the dots

Throughout the project, the journalists faced the challenge of identifying the real ownership behind shell companies. “If you keep staring at one entity, you’re not going to find it,” Pinster explained. “You have to connect different sources and think creatively,” he added.

Some links remained unconfirmed. “We started with over than 700 vessels; we ended up with 230 that we were sure of,” he noted.

Decisions about naming companies or individuals were made with great caution. “Each media outlet was responsible under its own legal system,” Schohaus explained. “Whenever there were doubts, we double- and triple-checked. Some partners delayed publication for extra legal review,” she added.

The team also debated whether they should include only the sales that occurred after certain sanctions milestones, but concluded that doing so would overlook the wave of transactions carried out preemptively—before the price cap was imposed. “They anticipated the price cap,” Pinster remarked. “Many of the vessels were already sold in the summer of 2022.”

Reactions and regulatory developments

As Eliza notes from experience, there is often intense pressure before publication. By the time a story reaches print, she adds, the goal seems to be avoiding stirring up any more dust.

Following its publication, The Shadow Fleet Secrets prompted questions in the parliaments of several European countries, as well as in Brussels. “There is a slow push to make the sector more transparent,” Pinster said. “But shipping has always lacked transparency. There is no overnight change.”

By early 2025, the European Union had already expanded its sanctions regime, enabling it to impose measures more easily on individual tankers and to add dozens more vessels to its blacklist. Asked whether the regulatory proposals mentioned in the investigation were eventually adopted, Pinster and Schohaus confirmed: “They’ve been approved,” they said. “There have been three new sanctions packages since then.”

Still, questions remain about enforcement. “A lot of individual tankers are now sanctioned,” Pinster noted. “But how effective are these sanctions? And what loopholes continue to exist? That’s something that we’re still looking at.”

Recently, there’s been an intense effort to stop you from publishing; to pressure you as much as possible before publication. If you do manage to publish, I think they don’t want to stir up any more dust.

Eliza Triantafillou, investiagtive journalist, inside story

Shipping accounts for nearly 8% of Greece’s GDP, and the country remains the world’s largest owner of tankers. Yet the investigation and its findings went largely unreported in Greek media —something Danai Maragoudaki believes may be due to the fact that “the country’s largest TV channels, newspapers, and news websites are owned by shipowners.”

As Eliza Triantafillou observed from experience, “Recently, there’s been an intense effort to stop you from publishing; to pressure you as much as possible before publication. If you do manage to publish, I think they don’t want to stir up any more dust.”

Takeaways from working together

For the journalists involved, the project was as much a lesson in cross-border coordination as it was in investigative reporting. “Make sure that you’re all on the same page about your definitions,” advises Birte. “We thought we were all on the same page, but towards the end we saw some differences between outlets.”

“In the last phase, everyone is in a hurry,” she adds. “It’s good to have your ducks in a row,” says Pinster, “because you can’t fix things a few hours before publication,” Schohaus notes.

The scale of the collaboration was unprecedented for many of the partners. Each media outlet brought local knowledge of ports, registries, and corporate networks that proved essential to linking the data and revealing the full picture at a global level.

Equally important was the approach to the data itself. “Give yourself time to understand what the story is and what your data actually shows,” advises Eliza Triantafillou. “Step back from the large datasets for a while; let the information settle.” She adds: “You’re not alone. Reach out to colleagues even outside your team.”

Deep understanding was more important than quick conclusions. “Focus on the gray areas, on the difficult parts. That’s where meaningful journalism lies,” says Danai Maragoudaki. Trust among collaborators was equally crucial. “Choose your teammates carefully and trust them to do their work well. This gives you the freedom to concentrate on your own tasks without having to check every detail,” she concludes.

Greek journalists have played a pivotal role in multiple investigations honored with the Daphne Caruana Galizia Prize. In 2025, Solomon and inside story took part in the international investigation The Shadow Fleet Secrets. In 2024, Efimerida ton Syntakton contributed to the Lost in Europe project, tracing over 50,000 missing migrant children. Earlier, in 2023, Solomon reporters were part of the investigative team the deadly Adriana shipwreck off Pylos, uncovering contradictions in official accounts and the Hellenic Coast Guard’s role.