Open-Source Mapping of events in Ukraine

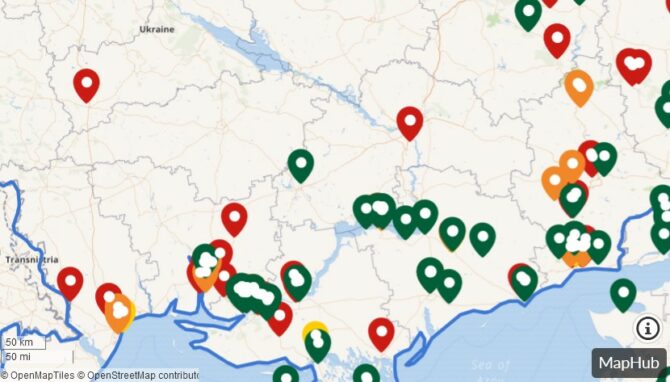

Centre for Information Resilience, Bellingcat, Mnemonic, Conflict Intelligence Team – collaborative initiative which aims at mapping, documenting and verifying incidents taking place in Ukraine.

As the war between invading Russian and Ukrainian forces grinds on, the civilian casualty count is rising.

In the early days of the conflict, the use of cluster munitions appear to have impacted sites around schools and hospitals.

Cluster munitions are a type of weapon that deploy a large number of smaller sub-munitions over a target. These sub-munitions then spread and explode over a larger area, increasing the potential for damage and casualties.

Due to the wide harm they can cause, cluster munitions are widely criticised as weapons that pose “an immediate threat to civilians during conflict” and for the “long-lasting” problems they can cause if sub-munitions do not explode upon first impact.

More than 100 countries have banned their use and signed up to the Convention on Cluster Munitions. However, neither Russia nor Ukraine (which also possesses cluster munitions) has put their name to this agreement.

Russia has continued to use them, most notably in eastern Ukraine in 2014 and later in Syria.

Ukraine strongly denied using cluster munitions during the conflict with Russian-backed separatists in the east of the country in 2015, despite a Human Rights Watch (HRW) report that stated they likely had.

In recent days, social media images and videos have allowed Bellingcat – along with other conflict monitors and open source researchers – to geolocate the impact sites of several cluster munitions to civilian areas within Ukraine.

We have also been able to determine the probable direction from which the missiles came, providing a clue as to who may have fired them.

In some instances, the number of casualties appears to have been significant.

For example, HRW have investigated and verified use of cluster munitions that landed just outside a Ukrainian hospital, pointing the finger of blame at Russia and calling for Russian forces to “stop using cluster munitions and end unlawful attacks with weapons that indiscriminately kill and maim”.

However, images and videos posted online demonstrate even wider use of these weapons in civilian areas.

Kharkiv

The city of Kharkiv in Ukraine’s north east, and just 25 kilometres (km) from the Russian border, has seen some of the most intense fighting over the last few days, with the Russian offensive reported to be stalling outside the city.

Kharkiv also appears to have been the target of multiple cluster munition attacks.

In the example below from 25 February we can see the effect of such a strike, with multiple submunitions detonating across a wide area. This stretch of highway (50.048093, 36.189638) runs through a residential area and is immediately next to a children’s hospital.

Although it’s not possible to identify the direction of origin of this particular attack, it is possible to do so for other strikes which also hit Kharkiv.

Russia, thus far, appears to have been firing cluster bombs from BM 27 and BM 30 multiple launch rocket systems (MLRS). We can tell this by the distinctive munitions used by each system and the direction from which they appear to have travelled before impact.

These rockets include a cargo warhead that contains the submunitions which separate from the rocket motor as part of its deployment. After the submunitions have been dispensed, the rocket motor and cargo warhead continue on their trajectory, frequently embedding themselves into the ground.

From these embedded sections, it’s possible to establish the general direction of origin of the rockets.

In this example, we see the motor for a BM 30 rocket embedded in a road in Kharkiv at 49.987345, 36.261194. Establishing the direction of travel is aided by the zebra crossing, as the image below details.

We’ve repeated this process for seven cargo warheads or rocket motors documented in open sources in Kharkiv and have identified that they appear to be coming from a north-north-easterly direction. In short, from the direction of the Russian border.

With maximum ranges of 35 km and 70 km respectively, BM 27 and BM 30 units could both be located in the relative safety of Russia while carrying out such strikes. This was a tactic used extensively during the 2014 war in Ukraine. However, it’s also possible that these units could have been stationed inside Ukrainian territory when they were fired.

The cargo warhead and rocket motors can continue flying for a significant distance after submunitions are released. As such, it may be that in some cases Russian artillery are aiming at military targets, but the motors and warheads are continuing well into civilian and urban areas – as the videos Bellingcat has seen and geolocated clearly show.

Yet, no matter the target, the impact has been demonstrably lethal and harmful to civilians.

Okhtyrka Kindergarten

There is also at least one example where it appears cluster munitions may have impacted the area around a kindergarten.

On 25 February, in the city of Okhtyrka, around 100 kilometres west of Kharkiv, an artillery strike caused several casualties (50.309797, 34.869819). These were reported to include children.

The following video depicts the immediate aftermath of the strike, including casualties.

This video also appears to show tell-tale black splashes (circled in the screen grab below) that indicate multiple submunitions impacted the kindergarten itself.

Bellingcat was able to geolocate a 9M27K cargo warhead which would have been fired by a BM-27 approximitely 200 metres east of the kindergarten.

In this case, the direction of origin points to the north-west-west, indicating it passed over the kindergarten.

There have been multiple social media reports of Russian troops in and around the city of Okhtyrka, before and after this attack, including posts claiming Russian soldiers were to the west of the city along the Okhtyrka-Zinkiv road and in the nearby town of Chupakhovka.

Translated example of a social media post warning about the presence of Russian forces.

Indeed there appears to have been a significant battle in the centre of Okhtyrka around the Heorhiya Peremozhtsya church 50.308362, 34.880200 on 24 February, where at least one Russian soldier was killed and his body filmed. There were also reports that multiple Russian soldiers had been captured there on the morning of the 25th February.

As such it is clear that the area around Okhtyrka is contested, unlike the area north of Kharkiv, which is under Russian control at the time of writing.

Considering that Ukraine also operates the BM 27 and BM 30, and the contested nature of the ground, there is currently not enough information to demonstrate with absolute certainty who fired this missile.

That said, it appears extremely unlikely that Ukrainian forces would fire this type of weapon deliberately into their own cities, even if targeting Russian soldiers.

Continuing to Track Cluster Munitions Use

Controlling the impact of cluster munitions is difficult at the best of times due to their inherently wide effect.

Even if used to strike a military target, away from immediate civilian presence, their dud-rate means they can frequently leave a deadly legacy of unexploded ordnance, often picked up by children or passers-by who might view them as objects of curiosity.

However, open source evidence from Ukraine appears to suggest that the cluster munitions highlighted in this article are not being carefully targeted. Instead, we have identified multiple examples that have impacted civilians, schools and hospitals.

As the fighting begins to move further into urban areas, there is a danger there could be significantly more examples of such usage of cluster munitions.

If you see any sources showing indications of cluster munitions, please reply to our Twitter thread here.

This article is a reproduction of the original article that can be found here.