This article was originally published by IJNET and was reproduced with permission. Any reprint permissions are subject to the original publisher.

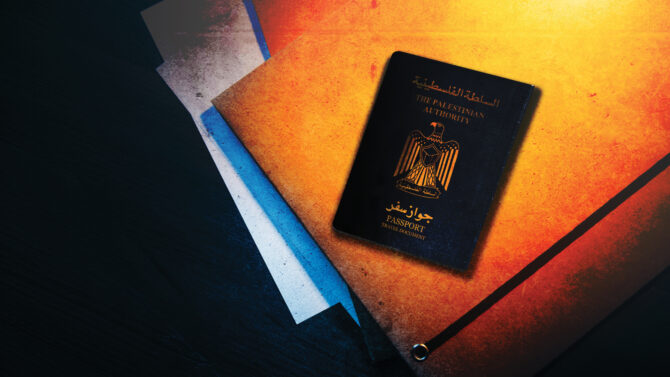

In Samos, on the run from Hamas

A Palestinian flees to Greece and seeks political asylum. He claims that he is being pursued by Hamas. iMEdD gained access to the case file.

Whether it be on WhatsApp, Facebook, X (formerly Twitter), Instagram, TikTok or news sites, people in Lebanon are increasingly consuming information online. With many ways to stay informed, however, there exists a heightened risk of stumbling across unverified news and false information.

Disinformation regarding Syrian refugees, who have recently been the targets of an intense hate campaign, has become especially prominent. In April, for example, an image showing a police ID supposedly issued to a man of Syrian origin was widely circulated, giving rise to racist comments online. Software used to detect doctored photos later proved that the document was false.

“It was a fake card made thanks to a photo alteration software,” said Ghadir Hamadi, co-founder of Sawab, a United Nations Development Program-funded platform specializing in the fight against disinformation in Lebanon. “There’s a lot of fake news affecting marginalized groups in Lebanese society, including Syrian refugees.”

Sawab, which was founded by six journalists trained in fact-checking and combating hate speech, counters false information primarily on WhatsApp. “We started to work on the messaging app because people use it a lot and forward news to their friends and families all day long. We created our own group on WhatsApp in which we hunt down false information,” said Hamadi.

Disinformation in Lebanon

Among the most popular forms of disinformation in Lebanon are false stories linked to the ongoing economic crisis, which began in 2019. “We’ve been dealing with a lot of lies about products that were supposedly going to run out on the market. I think that disinformation, above all, is fueled by fear,” Hamadi said.

Politics is another common topic around which disinformation spreads in Lebanon, said Jad Shahrour, communications officer at the SKeyes Center for Media and Cultural Freedom. “Lebanese society is very interested in this subject,” he said. “For every political event, you’re likely to come across several [different] versions.”

A study published in March by SKEyes shows that disinformation has invaded social media, alternative media outlets and “conventional” sources such as television throughout Lebanon. “Every generation has its social media platform, but disinformation is everywhere. Gen Z are on TikTok. Millennials are on Facebook, Twitter and Instagram. The influence of disinformation and fake news varies from platform to platform, but it’s definitely present on all sites,” said Shahrour.

[Young people] are aware that you have to tune in to several channels or consult several sites to really understand what’s going on, even if they have specific political affiliations,” said Shahrour. “People aged 60 and over, on the other hand, don’t automatically question the information they receive.”

The study shows that some people are more inclined to believe information disseminated by local religious figures, who are considered particularly trustworthy in remote regions, in place of information published by credible news outlets.

Shahrour pointed to the presence online of organized “electronic armies” as particularly worrisome. “[They are] deployed by certain major Lebanese political groups working to incite cult-related conflicts or sully the reputation of their opponents,” he said, adding that they tend to use fictitious social media accounts to do so.

Learning to spot disinformation

Faced with these multifaceted manifestations of disinformation, Sawab launched training courses in schools and universities, to equip students with best practices on how to spot disinformation.

“We teach them to use reverse search engines to find photos and videos,” said Hamadi. “For a photo, for example, we can try to find clues as to when or where an event took place. The same goes for a video. We can also try to contact local authorities or people in the field to check the veracity of a piece of information.”