In Sudan, an invisible humanitarian disaster continues to unfold, and journalism is a life-threatening endeavor. Sudanese journalists who have been forced to flee the country, international reporters, researchers, and experts speak to iMEdD about the challenges of covering the civil war, explaining how, beyond the cities themselves, even information is under siege.

Translation: Evita Lykou

Featured image: Evgenios Kalofolias

Sudan is one of the most dangerous places in the world to be a journalist, according to a recent report by Reporters Without Borders (Reporters Sans Frontières) for 2025. A civil war has been raging since April 2023, at the heart of which lies the conflict between the Sudanese Armed Forces (SAF) and the paramilitary Rapid Support Forces (RSF).

Since the civil war started, it has claimed more than 150,000 lives, and has led to the death of 16 journalists and media workers, according to data provided by the Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ). Notable cases include the murders of journalists Muawiya Abdel Razek and Taj al-Sir Ahmed Suleiman by the RSF in their own homes, in 2024 and 2025, respectively.

Gaza’s storyline: the coverage and the silence

With the ceasefire between Israel and Hamas being a reality, five journalists and media professionals share their perspectives on covering a war that has resulted in the highest number of journalist casualties in history. They assess the experience of the last two years and comment on the prospect of the next day –which has yet to come.

Journalism “under siege”

Journalists in Sudan “have been facing more than just the killing. We have the harassment, the arrests, the rape incidents, the hunger”, while kidnappings are also common. In the case of female journalists, sexual violence is used “as a weapon to threaten them and to silence them”, notes Sara Qudah, CPJ’s Regional Director for the Middle East and North Africa, speaking to iMEdD in an online meeting.

“We always say that Darfur and El-Fasher in specific are under siege. But to be more accurate, it’s not just the city that is under siege, it’s also the information, it is the media ecosystem, the journalists themselves,” Qudah continues.

Internet shutdowns and a lack of funding are also common, she says, while 90% of media infrastructure in Sudan has been destroyed. “The country is becoming like a black hole for independent reporting, where no information is coming out and no journalists are able to report freely and independently,” according to Qudah.

It’s not just the city that is under siege, it’s also the information. The country is becoming like a black hole for independent reporting.

Sara Qudah, Regional Director for the Middle East and North Africa, CPJ

What is happening in the Sudanese civil war?

The conflict between the SAF and RSF is the third civil war in the history of independent Sudan, which, since its founding in 1956, has known fewer than 20 years of peace. The current civil war has its roots in the 2019 coup that overthrew Omar al-Bashir, the country’s leader since 1989. Al-Bashir is accused by the International Criminal Court of being involved in the Darfur genocide and was president at the time of South Sudan’s secession in 2011.

The 2019 coup leaders – who until then had been Bashir’s associates– are now the leaders of the two opposing sides in the civil war. Abdel Fattah al-Burhan leads the SAF, and Mohamed Hamdan Dagalo, also known as Hemedti, commands the RSF. The two sides gradually became embroiled in conflict, primarily over the issue of integrating the RSF into the SAF, which would have downgraded Hemedti’s position.

Today, the war appears to have reached a strategic stalemate, while any attempts at mediation between the two sides have failed. The situation is further complicated by the involvement of foreign powers in the civil war, with the United Arab Emirates supporting the RSF, and Egypt, Saudi Arabia, Turkey and Iran backing the SAF. These third countries are motivated to intervene by Sudan’s gold, which goes primarily to the UAE and to a lesser degree to Egypt, as well as by the country’s access to the Red Sea and its trade routes. Broader regional disputes, like the one between Saudi Arabia and the UAE, are also playing out in the Sudanese civil war.

The fall of El Fasher

One of the worst atrocities of the Sudanese civil war occurred on October 26, 2025, when the RSF captured the city of El Fasher, the capital of North Darfur state, after an 18-month siege. Thousands of innocent civilians were killed, with widespread reports of sexual violence against women and girls. These massacres evoke memories of the Darfur genocide, in which the Janjaweed militias –which evolved into the RSF– played a pivotal role.

Following the fall of El Fasher, several journalists went missing. The most notable case is that of Muammar Ibrahim, who was abducted by the RSF on October 26, 2025. His fate remains unknown. Journalists who managed to escape the city report that they were subjected to threats and torture by RSF members.

Reporting in wartime: Anonymity, arrests, and blackouts

Haydar Abdelkarim, a Sudanese freelance journalist currently living in Kenya, left Sudan about three weeks after the outbreak of war. During this time, he continued to work for the Ayin Network, but the challenges he faced were significant: both the SAF and the RSF were targeting journalists from this outlet, who, fearing for their safety, were forced to publish anonymously. Power outages and internet shutdowns further complicated Abdelkarim’s work.

While attempting to leave Khartoum, the capital of Sudan, with a friend, they were stopped at a checkpoint by the paramilitary RSF who, upon realizing they were journalists, began “shouting at us, [discussing whether to] shoot us. But we were lucky: an airplane started bombing, so […] they took us inside some house and investigated us […] They checked everything: our laptops, mobiles, our luggage, trying to confirm that we are not part of the SAF. After six hours they allowed us to go,” he tells iMEdD via teleconference.

They began “shouting at us, [discussing whether to] shoot us. But we were lucky: an airplane started bombing, so […] they took us inside some house and investigated us. After six hours they allowed us to go.

Haydar Abdelkarim, Sudanese freelance journalist

Continuing their perilous journey, they arrived in Al Qalabat, a small town on the border between Sudan and Ethiopia. There, when the SAF “scanned [the passports], they found out we were journalists […]. They immediately kept our passports and […] arrested us for more than eight hours.” That day, they missed their chance to obtain visas for Ethiopia.

The RSF also targeted Eisa Dafalla, a Sudanese independent journalist who now lives in Uganda and with whom we managed to speak via text messages and an internet call, once the internet in the country was restored following the recent elections.

On his way to work at a market in Nyala, the capital of South Darfur state, on May 15, 2023, “I had a camera, my phone and a cameraman working with me […] some RSF soldiers came and asked me why I came to work in the market and told me that it is not allowed to work here.” They then arrested him, taking his equipment and all the money he had on him. “In the evening an attack started and they told me, you can go, but you cannot come back here.” This arrest was one of the main reasons that led Dafalla to leave Sudan.

Covering Sudan, outside Sudan

Despite the hardships, Sudanese journalists have found ways to adapt, with hundreds fleeing to neighboring countries, particularly Egypt, Uganda, and Kenya, from where they continue to report on the civil war.

From Uganda, Dafalla continues to shed light on human rights issues, particularly in the Darfur region, working mainly with the Sudanese media outlet Jubraka News, but also with international media outlets such as The New Humanitarian and The New Arab. “One of the main challenges” he faces “is the refusal of officials on both sides of the war to provide statements. Each side prefers to share information only with journalists who support their position.” Although he is now outside Sudan, he continues to receive threats because of his work.

Following his relocation to Kenya, Abdelkarim has focused on covering issues related to the civil war, with a particular focus on Darfur, his place of origin, while collaborating with outlets such as Ayin Network and The New Humanitarian.” However, accessing sources within Sudan is difficult as both the SAF and the RSF monitor communications, he says. As a result, “sometimes even our family is very scared to talk to us.” In Darfur, he adds, the internet connection is very expensive: “Sometimes I spend more than a month just to talk to sources there because they don’t have money for the internet.”

Sometimes I spend more than a month just to talk to sources in Darfur because they don’t have money for the internet.

Haydar Abdelkarim, Sudanese freelance journalist

One of the main challenges exiled journalists face is that “we are no longer present at the scenes of events,” which makes it difficult to verify information, says to iMEdD Hassan Berkia, a freelance journalist from Sudan who lives in transit between Egypt, Uganda, and the United Arab Emirates. The civil war has exacerbated pre-existing ethnic tensions, which also affects the trust between journalists and their sources, Berkia tells us in a WhatsApp text. “On many occasions, sources have questioned my ethnic background and place of origin,” he continues, while others have expressed “profound suspicion if they perceived me to be from a different geographical region than their own.”

Berkia highlights the dire situation that female journalists in Sudan face, noting that many have been forced to flee the country due to ongoing sexual violence.

The civil war has exacerbated pre-existing ethnic tensions, affecting the trust between journalists and their sources.

The international perspective of a Greek journalist

Journalists from international media outlets who attempt to cover the story also encounter obstacles. Alexia Kalaitzi, a journalist with ERT and the newspaper Kathimerini, traveled to the region on assignment in December 2025, to report on the lives of Sudanese refugees living in camps across neighboring Chad, for ERT’s program Fasma.

It was “virtually impossible”, she says, for the team to enter Sudan, given that in a war zone security concerns are immense, and“the logistical support required is something that a TV channel from a country like Greece cannot easily manage.” Even in Chad, however, the team also faced a series of challenges, ranging from complex bureaucratic procedures to the difficulty of finding “fixers” from Sudan. In the absence of local journalists, the assistance of Médecins Sans Frontières Greece was invaluable.

Speaking to iMEdD from Athens about the ethical challenges she encountered, Kalaitzi recalls the case of a severely ill woman who had fled the city of El Fasher in Sudan. “Getting this person to ‘open up’ in order to provide information from a city we have no knowledge of (information which, from a journalistic standpoint, is a treasure), while, at the same time, ensuring that this interview wouldn’t make her situation worse, was one of the most difficult things I’ve dealt with as a journalist.”

Cross-checking information while investigating a civil war

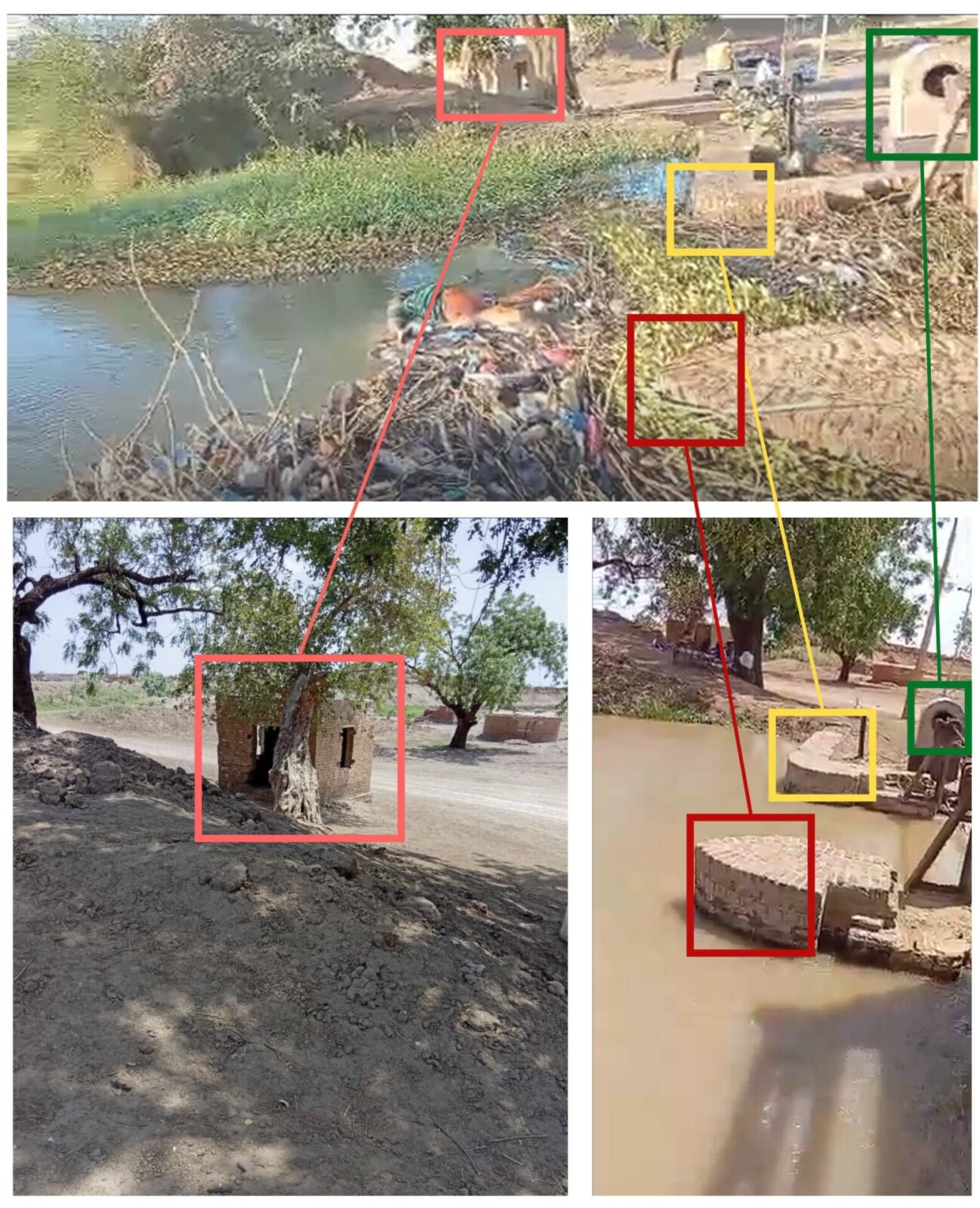

Precisely because of the dangers involved in practicing journalism in Sudan, Lighthouse Reports combined different methods to investigate crimes committed by the SAF, according to Aziz Alnour, Investigations Editor and a Sudanese investigative reporter who has also been living in Uganda for several years. Through on-the-ground reporting, open-source intelligence (OSINT), and collaboration with local Sudan War Monitor journalists (a group of journalists and OSINT researchers documenting the civil war), Lighthouse Reports revealed that the SAF have carried out mass killings and displaced farmers from non-Arab communities known as Kanabi, who live in Al Jazira state.

Reporting from within Sudan proved invaluable, as it gave the Lighthouse Reports team access to survivors of the crimes as well as whistleblowers. Yet it also presented several difficulties: while traveling, journalists often had to pass through SAF checkpoints where “the journalist’s devices have to be inspected and checked,” Alnour reports. The riskiest part of the investigation, however, was meeting with sources from the SAF because “the sources themselves are very risky.”

The use of OSINT in areas where access is difficult, like in Sudan, “is definitely an opportunity, but it has limitations,” emphasizes Sabrina Slipchenko, who led this part of the investigation.” Through investigating social media posts –mainly on Telegram and TikTok– and using techniques such as geolocation and chronolocation, the Lighthouse Reports team verified SAF attacks against the Kanabi, which had been reported in earlier interviews conducted for the field reporting.

To avoid the pitfalls of misinformation, Slipchenko says, they used information from different sources, such as satellite images and databases, in order to cross-check and verify their own data..

An “invisible” humanitarian disaster

Arguably the world’s largest humanitarian crisis today, the Sudanese civil war has forced more than 13 million people to flee their homes. More than 21 million people, around 45% of Sudan’s population, face high levels of hunger, according to data from the Integrated Food Security Phase Classification (IPC). Meanwhile, both the SAF and the RSF have committed war crimes against civilians, while the US has recognized that the RSF have committed genocide.

The war, however, is not receiving the attention it deserves. At the iMEdD International Journalism Forum in September 2025, Christina Psarra, General Director of Médecins Sans Frontières Greece, spoke about her visit to the region: “When I returned, I thought that I would be talking about it for a long time. But I could hardly find anyone -not just the media, but also people- who were interested in what was going on.”

Why have the media paid so little attention? Sudanese journalists and Kalaitzi both agree that other crises, mainly in Ukraine and Gaza, have overshadowed the tragedy in Sudan. Tessa Pang, Impact Editor at Lighthouse Reports, adds that there is a lack of access to reliable information about the situation inside Sudan, coupled with a “lack of public knowledge and understanding of the war”, which international media often interpret as absence of interest and understanding on behalf of the public.

The war in Sudan is not a “forgotten war,” but a willfully neglected one. Sudanese lives have been traded away to serve external interests.”

Hassan Berkia, Sudanese freelance journalist

However, the international community bears the greatest responsibility for the situation in Sudan. “We must understand that we are not merely passive observers. Our countries have a responsibility to help resolve this conflict,” Kalaitzi points out. For Berkia “the war in Sudan is not a “forgotten war” […], but a willfully neglected one. Sudanese lives have been traded away to serve external interests.”