Russian troops in Ukraine are compiling lists of journalists for questioning

RSF – Reporters Without Borders reminds the Russian authorities that targeting journalists is a war crime

Journalists who’ve worked extensively in México, Gaza and Eastern Europe discuss low pay, safety issues and lack of credit and respect.

“They are not ‘fixers’. They are journalists. They are not ‘fixers’. They are production managers. They are not ‘fixers’. They are producers. RIP Oleksandra Kuvshynova[.]” reads Marcus Ryder’s tweet paying tribute to journalist Kuvshynova, also known as Sasha, who was killed on 14 March near Kyiv while working with a Fox News team to cover Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

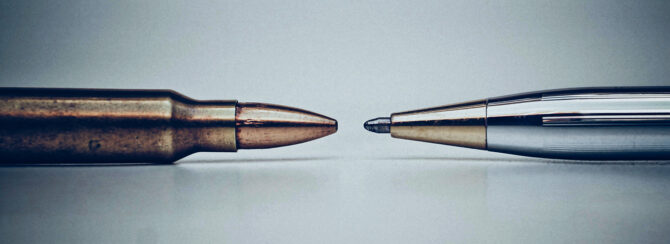

In the wake of Kuvshynova’s death, fellow journalists shared stories of the critical role played by journalists who work as field producers, translators and production managers with international media outlets when their country or region becomes the story. “I’ve only met a few war correspondents whose lives were saved by a bulletproof vest. But all of us have been saved at least once by our own fixer,” tweeted Óscar Mijallo, who’s covered the war for Spanish public broadcaster RTVE.

A catch-all term for people who provide language skills, cultural and regional understanding and a strong network of contacts on the ground, “fixers” are a crucial part of foreign correspondence. When a conflict or a news story hits international headlines, journalists working locally and regionally will frequently fill this vital role. I’ve spoken with journalists who have worked extensively as local producers in México, Gaza and Eastern Europe. They discuss some of the challenges of this job.

Colleagues who don’t show respect

“My problem with the word fixer is that it doesn’t convey the respect that it should. A good fixer is [often] a good journalist. We like to call it field producing rather than fixing,” says Vicente Calderón, director and editor of Tijuana Press. Calderόn has worked with international media for around 30 years, covering the border region between México and the United States. “We fix things but don’t call us fixers,” his Twitter bio says.

Media from “out-of-town” can come to a place with a preconceived idea of the story they want to tell. Sometimes they have seen coverage they are just happy to repeat, Calderόn says. “They don’t have much respect for what you have to do to create a story from scratch, to be truthful, and to do real journalism,” he says.

While his experience has been largely positive, Calderόn says attitudes from international outlets towards Mexican journalism can compound this lack of respect: “It’s been changing during my career, but Mexican journalism doesn’t necessarily have the best reputation in México, let alone in the US.”

Second-rate pay and conditions

Journalists working with international media must know their value, says London-based journalist Vudi Xhymshiti, especially when covering breaking news events. It is often their skills, local connections or cultural understanding that can make or break a story or solve a problem for a news outlet. War correspondents need these skills to work: “If the media are not prepared to pay for this and they just want to take advantage of you, then that’s it, finito. At the end of the day, this is the month when you can earn something and it may never happen again, so you have to be paid properly.”

“You have to put your money where your mouth is. We don’t deserve any less than what media professionals get in their own country. We shouldn’t accept anything less,” says Calderόn, who recalls being asked to produce and cover stories in the US from Tijuana in the hope that he would do this at a cheaper rate. “Be fair and be respectful as you are with your own professionals. If we don’t have a good environment and conditions, you can’t expect to have good journalists,” he says.

Ameera Ibrahim Harouda is a freelance journalist in Gaza, Palestine, and has worked regularly with international outlets since 2004. She will arrange all aspects of a foreign journalist’s trip: hotels, sourcing reliable internet connections and lining up interview permissions, filming in the field, translating reports and collating archive materials. “They can’t get into Gaza without permission [a local, approved sponsor],” she says – another role she fulfils.

“I was the only woman when I started and many men tried to fight [against] me. They would call my dad and ask him to take me home,” says Harouda. When she first started, the prejudice wasn’t just against her gender: if you worked with foreign media, you were considered to work on behalf of Israel too.

In nearly 20 years, Harouda has covered multiple wars and border protests, and has worked with press, radio and TV outlets from Europe, Australia and the US. In times of war, she will often report and film from the field, including from bomb sites and hospitals, sending a rough cut of footage to reporters.

This range of work, in particular pre-reporting, is not always reflected in field producers’ pay, says Xhymshiti: “Doing the research, preparing, arranging meetings for them before they arrive in the country? That’s a working day and I have demanded to be paid equally and full-time. I was once offered 20% payment and I said: ‘No, go and find somebody else who will do it for free like that.’”

Maintaining a united front

Xhymshiti now runs his own photojournalism and production agency providing production services in Eastern Europe and the Western Balkans to news organisations worldwide. He is currently hiring field producers and communication production assistants – a term preferred to translators – in 20 different countries. The agency can help freelancers and producers in in-demand regions manage requests and negotiate terms. Sometimes news organisations try to renegotiate an agreement for less pay by going directly to one of his producers. But he asks them to maintain a united front.

“If they want to produce something, they’ve got to respect your integrity as a person,” he says. “If they’re playing like this, they have to face the consequences of their actions because it may now be very difficult to find someone ]to do the work].”

Establishing good working practices

All of the journalists who spoke with me for this story stressed that they had had multiple positive experiences of working with international media outlets. For Calderόn good communication from the start is vital, especially to learn from and understand the working practices and editorial policy of your international partner.

“Respect is a two-way street. When working with professionals with the background of big institutions, we try to be as good as they are. We try to ensure our standards are the same,” he says, adding that this may involve adapting your approach to a story to accommodate the rules of the country your media partner is from.

Without this mutual respect for the producer and the story, however, coverage can suffer. When working with an international outlet to cover El Chapo’s arrest in México, the international journalists turned up late because of a previous engagement. As Calderón had warned, access to the jail was no longer possible. “They reacted late to the story and we were not able to provide what they were asking for,” he says.

Xhymshiti recounts good experiences with Der Spiegel in Albania and Kosovo, and with Norwegian media in Kosovo and Serbia. But he had to push back against pressure on other jobs, especially when first starting out: “I had to compromise with their demands. It was intimidating. I needed the money, I was young and living independently from my family because they refused to support my intentions to become a journalist.”

Calderón sets expectations clearly at the beginning of a project: “I always ask them in advance: what are your expectations? What do you want? If they have an idea that we don’t feel comfortable with, we pass them along. There’s no amount of money worth enough to take too much risk. We have so much corruption that there are no guarantees you’re going to be protected.”

Safety matters

It may be harder for less experienced journalists to resist job offers for low pay or work that may jeopardise their safety. “If we lose one client for safety reasons, we will still be able to work with somebody else. That could be different for someone who is beginning and trying to establish themselves or someone who is not as ethical,” Calderón says. He recommends making your own risk assessments and setting your own terms where possible. He has seen other production crews take on jobs he has turned down on the basis of safety concerns only to see them have gear stolen and be “held for a while”.

In the training Xhymshiti offers to field producers, he makes participants aware of this personal responsibility too: “If there is something you don’t want to do, you should not do it. It doesn’t mean that you will get fired from the job or that you will not be asked to do the job anymore. It just means you have a clear understanding that your safety is your priority. You have to first be aware of what it takes to do what you do. If that means direct consequences for you, then you should consider and weigh it out.”

Xhymshiti says news outlets must include journalists working in these roles on their life and health insurance policies: “It’s a job I agreed to do [but] if I’m disabled for the rest of my life because I’m working with you I have to have ways to make a living.”

Making these assessments can keep both producer and incoming international journalists safe. “In certain places, if you aren’t local and familiar with what’s going on in that area, you may put yourself and the people with you in danger,” says Harouda.

The results of the Global Reporting Centre’s 2016 survey of more than 450 people from 71 countries suggest disparities between foreign journalists and field producers: more than 70% of surveyed journalists said they “never or rarely” placed a fixer in immediate danger, while 56% of field producers said they were “always or often” put in danger.

Personal risks and rewards

The risks to the producer may not be immediately apparent to those unfamiliar with a place or a situation. Harouda has been misrepresented before at the point of publication, with a final edit of a report suggesting she worked for Hamas and that was why she had been able to secure an interview with a Hamas official and help the film crew on the ground.

“Not all of the international journalists understand what I am dealing with. They just want to cover the story and leave. They don’t know that this is a whole life for the fixer that they are working with in Gaza,” Harouda says.

Some reporters will discuss the final piece with her before publication and sometimes her translation work also allows her to assess whether the coverage is representative of the situation in Gaza. “Some come with their own ideas and don’t know how things here work,” she says.

The stories produced can have consequences for the journalist who stays on, whether through political fallout or simply because it is their phone number that sources have. “The journalist you are working with will leave Gaza, but I won’t. This is the work of my life. I can’t find myself in another field,” Harouda says. She has maintained many relationships with international journalists after they leave Gaza and says some former colleagues offered support to her family when COVID-19 affected her ability to work.

As the first female field producer in Gaza, she has assumed a great deal of risk responsibility for herself and her family when working independently and with foreign media. Often acting as their local sponsor for entry into Gaza, she will be held responsible for their work. Despite these responsibilities and her contributions, not all the international outlets she works with give her credit or a byline in their reports, something she would like to see changing in the future.

“It’s a risky job and hard job, but I enjoy it. It gives you a chance to meet more people, including officials. It gives you a chance to better understand your society,” she says.

Credit where it’s due

In the Global Reporting Centre’s 2016 survey, 60% of journalists stated that they “never or rarely” give fixers credit while 86% of fixers said they would like credit “always or sometimes”. Without consistent crediting, field producers take on great risks as part of their work, especially in conflict zones, but their names only become more widely known if they are killed or kidnapped.

Harouda has plans to set up an independent office for female journalists in Gaza. She would like to use her experience of reporting and working with international media to support other women in the profession and strengthen coverage of Gaza.

For Calderón too, working with international outlets not only provides income but an opportunity for Mexican journalism and coverage of the border region. “This is the way that we fund our local operation. The opportunity to work with other media outlets gives us the opportunity to be more independent as local Mexican journalists,” he says.

“We have found a niche,” Calderón says. “We can make things easier and faster and more productive for them by operating in this niche. Nobody else was systematically doing this as a service for other media outlets when we began and that has been the best way to maintain being an independent journalist in México.”

Laura Oliver is a freelance journalist based in the UK. She has written for the ‘Guardian’, BBC, ‘The Week’ and more. She is a visiting lecturer in online journalism at City, University of London, and works as an audience strategy consultant for newsrooms.

This article is a reproduction of the original article that can be found here.