Microchips are at the core of the global industry, underpinning technological innovations such as AI, factory automation, electric cars, and advanced weapon systems. At the same time, they lie at the heart of the US-China trade conflict—a “Cold War” dispute with significant global implications.

The US-China clash over electric cars

Protecting the economy or the environment? Who will win the EV race? And why are French cognac producers worried? Nicholas Lardy, a senior fellow at the Peterson Institute for International Economics and a vice chair of the National Committee on US-China Relations, speaks to iMEdD from Washington, DC.

“Standing here before a mural of your revolution, I want to talk about a very different revolution that is taking place right now, quietly sweeping the globe without bloodshed or conflict,” US President Ronald Reagan began his speech at Moscow University. He was addressing dozens of graduates in front of a mural of the Russian Revolution and a huge marble bust of Vladimir Lenin.

It was May 1988. The place and the introduction of his speech were not at all accidental. The Cold War between the United States and the Soviet Union had come to an end. The military arms race had “slowed down” and the US was already investing in a different kind of power: computing power.

“It’s been called the technological, or information revolution. And as its emblem, one might take the tiny silicon chip no bigger than a fingerprint,” Reagan continued, referring to technological achievements that the Soviet Union had failed to replicate.

Six decades after the invention of the microchip in the US in 1958, and nearly 40 years since the end of the Cold War, tiny electrical circuits are once again at the forefront of a new global rivalry: the US-China trade conflict.

From microchips to neural networks

Microchips, whether advanced or less advanced (legacy chips), are rightly considered the new oil. They are embedded in the control systems of devices like microwave ovens, the cores of smartphones and cars, and weapon systems, providing the necessary computing power. This power translates into millions of binary arrays, where ‘1’ represents an ON state and ‘0’ represents an OFF state in electrical signals.

The pace of innovation in microchip manufacturing is unprecedented. “Microchips consist of transistors, (or transfer resistors), which are electronic ON/OFF switches,” explains Christos Sotiriou, a professor at the Department of Electrical Engineering at the University of Thessaly, specializing in digital circuits. Fifty years ago, Gordon Moore, the co-founder of Intel, observed that the number of transistors that could fit on a microchip would double every 18 months. At that time, a microchip contained just four transistors. Today, they number 11.8 billion.

“They are solid-state structures that don’t require gas like the lamps did. Today, we are in the era of very high integration, with billions of transistors on a microchip, whereas you can fit about 10,000 transistors on a human hair,” says Christos Sotiriou.

US-China Trade War: Competing on the Economic Frontline with Dr. Konstantinos Tsimonis

We talked to Dr. Konstantinos Tsimonis, Senior Lecturer in Chinese Society at King’s College London and a member of the Institute of International Relations. We discussed the intricate dynamics of the U.S.-China trade conflict and whether we are witnessing a new Cold War.

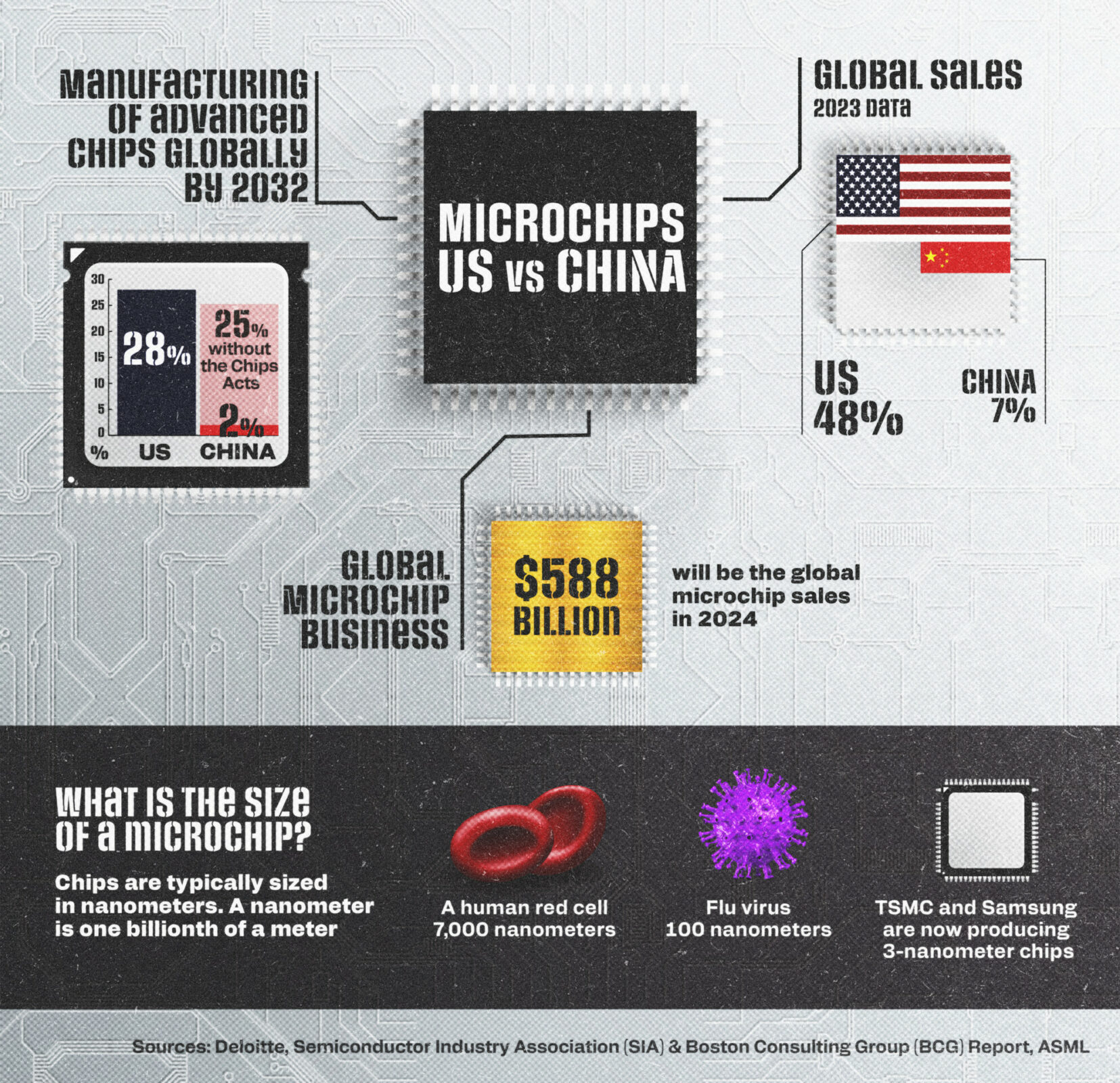

In April 2024 alone, global microchip industry sales reached $46.4 billion, according to the Semiconductor Industry Association (SIA). Although the US still leads in microchip design, manufacturing has been outsourced for decades to countries like Japan, South Korea, and Taiwan. Today, the US produces only 12% of the world’s microchips, a third of its production in the 1990s. Meanwhile, China is increasing its market share in the manufacture of less advanced microchips (legacy chips).

AI applications rely on advanced microchips. “Every time we do a Google search, it goes to a TPU (tensor processing unit) that uses machine learning technologies to find results faster. So AI needs a microchip. It’s all interconnected,” explains Professor Sotiriou.

The US-China dispute over control of the microchip industry intensified in October 2022, when the US imposed export controls aimed at restricting China’s access to advanced technology for both competitive and national security reasons – the “Chips Act” series of measures. These restrictions were designed to reverse at least 25 years of trade relations that had been based on mutual economic benefit between the world’s two largest economies. However, in the years leading up to this, both the US and China had been attempting to reduce their dependence on each other.

The Chips Act was not the first US move on the chessboard. As early as 2017, they tightened export controls on equipment for producing advanced microchips. Today, the restrictions also apply to non-US suppliers, including companies based in Japan and the Netherlands. At the same time, the European Union created its own version of the Chips Act, the European Chips Act (ECA), allocating nearly €5 billion in research and development (R&D) funding. The European Union’s goal was to gain 20% of the global market share in the microchip industry by 2030.

Taiwan in the spotlight

Taiwan is at the center of the US-China trade competition. The island nation – half the size of Ireland and with a population of 23.5 million – lies off the southeast coast of China and north of the Philippines. Its location is of great geopolitical importance, as tens of thousands of merchant ships pass through the Taiwan Strait on their way to the Pacific Ocean.

The microchip industry accounts for 15% of Taiwan’s GDP, with Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co. (TMSC) maintaining a global monopoly on advanced microchip manufacturing, controlling 90% of the global market. Founded in 1987 by Morris Chang, an American university graduate who played a key role in developing the microchip industry in the US and later transferred his expertise to Taiwan, TSMC has greatly profited from the ongoing AI boom. Today, TSMC partners with major design companies like Apple, Intel, Qualcomm, and Nvidia to produce “custom microchips.”

In recent years, Chinese officials have been vocal about Taiwan being part of China, even threatening invasion for reunification. Conversely, the US, while not officially recognizing the state of Taiwan, has indicated readiness to assist militarily in the event of a Chinese invasion. Both sides, however, recognize that a conflict and a blockade of Taiwan would have a serious impact on the global microchip market, potentially triggering a trade crisis.

“Global production depends on Taiwanese microchip production, precisely because the US outsourced much of its production starting in the 1980s,” Barath Harithas, senior fellow in the Project on Trade and Technology at the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS), tells iMEdD.

Despite the intensification of naval exercises around Taiwan, Mr. Harithas does not believe a Chinese invasion is imminent. “It is difficult to invade Taiwan,” he explains, noting that the cost of such an operation has been vastly underestimated. “Unlike Ukraine, which shares a large border with Russia, Taiwan is an island surrounded by whirlpools. Moreover, there are very few accessible beach landing zones for troops,” he says.

Investment and introversion

The next day sees both countries racing to invest in their domestic microchip industries. On one hand, the CHIPS for America program provides for approximately $30 billion in funding and offers loans of up to $25.1 billion to 12 companies across 21 projects in 13 states. As reported by the Semiconductor Industry Association (SIA), the US plans to invest at least $348 billion by 2030. On the other hand, China is establishing a $47.5 billion fund aimed at enhancing domestic manufacturing capabilities.

“The amount of investment from both sides is impressive,” Harithas tells iMEdD. In China’s case, the realization that it has been importing more microchips than exporting since 2010 prompted Beijing to pursue autonomy, officially launched in 2015 with the “Made in China 2025” program.

Last April, the Biden administration, in an effort to relocate some of its microchip production to US soil, provided TSMC with a $6.6 billion grant. It’s worth noting that TSMC had previously announced in 2020 the construction of three plants in the state of Arizona, with the first expected to start producing microchips in 2025 and the second in 2028.

However, “exporting” the Taiwanese work culture to the US may run into problems, says Harithas. “Taiwanese (microchip) factories, are characterized by a military-like culture,” he says. “Workers typically commute on Mondays and reside in on-site dormitories until Thursdays, enduring long hours with little margin for error. It is a tough industry with very difficult working conditions and high expectations. I don’t think American workers will accept exporting this model to America,” he notes.

In January 2024, Intel CEO Pat Gelsinger remarked at Davos that China lags a decade behind technologically in the global race for advanced microchip manufacturing, largely due to US and international restrictions. However, this does not deter the US. “(China) is striving for autonomy in at least ten different technologies,” Harithas tells iMEdD. “I think part of the trade war also stems from concerns that China, if successful, could surpass the US.”

Read all articles and analyses of the Special Report: “US-China Trade War” here.