This article was originally published by Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism on 20/12/2023 and is hereby reproduced by iMEdD with permission. Any reprint permissions are subject to the original publisher.

The 22-year-old shares why she’s shown both destruction and humanity to TV audiences and to her four million followers on social media

Many journalists have risen to prominence since Israel began bombing Gaza. With most international reporters barred from entering the Strip, those already on the ground have become the primary means by which many around the world are learning about the unfolding devastation.

Plestia Alaqad is one of those journalists. She is 22 and her coverage of the war appears on her own social media channels and through established news networks such as ITV. Before the war, she interned and worked at a number of news media organisations including Press House Palestine, which provides training and support for journalists and whose director Bilal Jadallah was killed in November by an Israeli airstrike.

Alaqad’s dispatches provide a very raw account of the bombing, destruction, forced displacement and struggles to survive in the territory. But they also show the humanity of Gaza and its people. Her Instagram account, where she posts as @byplestia, and which has well over four million followers, features visuals of herself playing with children, finding hope in befriending a turtle and reminding her followers what Gaza was like before the invasion.

Almost a month ago, Alaqad was able to leave Gaza after family members in Australia helped her obtain an emergency visa. She described this move at the time as “literally one of the hardest decisions that I took.”

I spoke to her on her approach to journalism, how she and her colleagues supported each other during the conflict, and what impact she hopes her work will have.

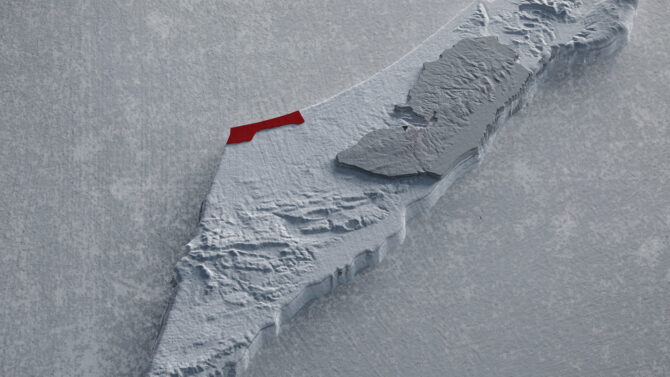

Where and how journalists are being killed in Gaza

An interactive map of where and how journalists and media workers were killed in the Gaza war, according to CPJ data.

Q. How did you get into journalism and what were you doing before the war started?

A. I studied New Media and Journalism and I graduated in 2022. So I was almost a fresh graduate before the war. I worked in journalism but also in human resources. I gave media training programmes and workshops at Press House Palestine [a non-profit organisation that supports journalists across Palestine]. I used to do many different things: I took internships at Alghad TV and as a news editor at the Sawa news agency. I was trying to explore the media industry in Gaza.

While I was [studying] in Cyprus I liked to cover good news. I like to cover celebrations, happy moments. These are the types of things I like to document. So while I was at [Eastern Mediterranean University], I worked as editor-in-chief and reporter of Gündem Newspaper. I remember that the last thing that I did was covering the graduation and how the graduates were feeling and what were their expectations.

Then suddenly I found myself reporting on the genocide of my own people. It’s crazy to think about the type of work that I was doing before 7 October and after that date.

Q. Can you remember how you felt as a journalist when the war started?

A. During the war, I didn’t have time to feel emotions. Crying or feeling emotions was a privilege. Sometimes I was hopeful that it would end soon, that things would get better. Then the next day something really terrible happened. Sometimes I used to think like: ‘Enough today. We reached the worst point. Nothing worse could happen.’ The next day something even worse happened. So it was devastating. I didn’t have time to understand or process what I was feeling.

Q. What were your daily routines when you were covering the war from within Gaza?

A. There was no daily routine during the war because you don’t know what’s waiting for you. Some nights were sleepless. I was just up all night waiting for the sun to rise to see if I’d make it alive another day or not. Some days I wasn’t able to work or move around because we didn’t have fuel. Some days I lost connection with the team I work with because [there was] no service or cellular connection. So it wasn’t easy at all to work with no electricity, the lack of internet, the lack of everything.

Q. What kind of safety precautions did you take while reporting?

A. At the beginning I used to always wear my press vest and my press helmet because I’m a journalist and I wanted anyone to recognise me as press. Then I started to feel more in danger actually wearing them, so I stopped. I made a post about it on Instagram. At first, in all my pictures I was wearing it the whole time. I felt naked not wearing the press vest and helmet. But then I [felt] it was only bringing me back problems and danger, so I didn’t see the point.

Q. You show the devastation of the war in your work but also moments of happiness and people persevering. How do you decide what to cover?

A. I never decide on what to cover. On the day, the story calls me. I don’t go for the story, the story searches for me. I don’t plan ahead. You can’t plan ahead of time. I just see it and I know that this [is something] the world should see. In general, I’m an optimistic person. Like, I love life, you know? So even during the war, I was obviously devastated. I was traumatised with everything that I was seeing and covering, but I always made sure that whenever I saw a little kid, I tried to lift them up. I don’t [approach] people only as a journalist. I am a human before being a journalist so I always make sure to build connections with them, to talk to them you know. Filming the story and leaving is not a job for me. No, I’m a human and they are humans as well. We all are stories.

Q. What was the reaction of Gaza’s residents to you as a journalist?

A. Different people had different reactions. Some people were very welcoming, very appreciative of journalists, of all the hard work that we’re doing. Many people fed me, for example. Like, I’m just working, doing my job, and they’re like, ‘eat bread, drink this tea’. People were so generous even when they have nothing to give and they appreciate and understand how tiring the job is. Some people were actually afraid of journalists [being around] because they saw how many journalists got killed.

Q. What effect has the war had on your emotional wellbeing and how has it affected your work?

A. I’m still in the processing phase because the war is not over. Even though I’m physically out of Gaza, I’m not mentally out of it. I still haven’t had a moment to catch my breath or process any of what happened. But everything that has happened made me feel that life is pointless. Like, ‘What is life? What is death?’ It made me regret being sad over anything. I remember I once cried, for example, [before the war] because my mug was broken. And [now] I’m like, ‘I wish all my mugs were broken!’ I remember thinking there’s nothing to be more sad about than everything that’s happening. I saw children cut into pieces.

Q. How were you able to carry on?

A. It’s not like I had any other option. But one thing I love about me and my colleagues, the team that I was working with, we used to always lift each other up. Everyone is tired and devastated. Everyone wants a ceasefire and wishes to unsee what we saw, to unlive what we lived, if that makes sense. But we try to always support each other, keep filming, keep working on what the world needs to see. We can’t stop now. We can’t be tired. We were the ones who needed emotional support the most but we were the ones who gave it to each other.

Q. You said in one of your posts that leaving Gaza was one of the hardest decisions of your life. Why did you decide to leave?

A. The more news there was of journalists getting targeted or the more news of families of journalists getting targeted, the more terrified I was. Seeing Wael Dahdouh’s family [be killed]and seeing Bilal Jadallah getting murdered [terrified me]. The day before I travelled, two journalists got killed. It’s not about my own safety, it’s about my family’s safety as well. What if something bad happened to them because I’m a journalist? I know bad things happen to everyone. I know even civilians are not safe in Gaza. But if your family is getting specifically targeted because you’re a journalist, it’s crazy to think about that.

Q. Does the large following that you and journalists like you have gained on social media give you any hope?

A. I appreciate how I’ve raised more awareness about what’s happening in Palestine. But I also hate that it’s only now that they know Gaza. That’s why I always post about life before 7 October. We are people. We have lives, dreams, hopes. We are just humans, you know. We are not built to see all these killings, the blood, the demolition. We just want to have a normal life. I also hate how they never knew how beautiful Gaza is because now there’s nothing left in Gaza. Everything got bombed. I feel that I want them to know about what’s happening now and about us as humans and about how pretty Gaza was and will always be.

Q. What impact do you hope your work has in the long term?

A. I hope more people know about Gaza and I hope they know what’s happening didn’t start on 7 October. I want them to know that we have been living for 75 years under occupation. I just want the younger generation as well to learn about Gaza, about Palestine, to know about its culture, about its people. I want them to know about us. I want the world to see us as humans.