How can journalists avoid the good news trap, be part of the solution in a problem-focused industry, and distinguish their content from traditional media outlets? Juliette Gerbais talks with iMEdD about Solutions Journalism and the quest for answers to present challenges.

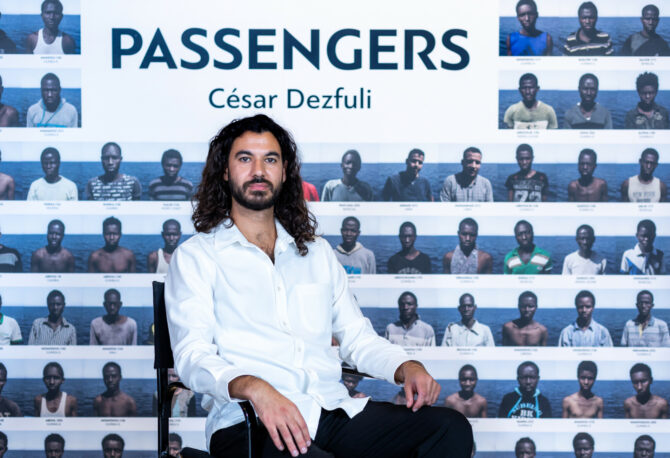

The faces behind the numbers: César Dezfuli’s “Passengers”

César Dezfuli’s images narrate the stories of the central figures in the refugee/migration crisis in Europe, going beyond mere statistics and numbers.

Things go wrong, and one should report them efficiently and accurately. In the modern-day media landscape, talking about significant problems is the primary focus of journalistic stories. But since the seventies, the news has become increasingly hostile, a fact which has been reported to have a devastating effect on the audience’s mental health. With two ongoing wars and amidst the climate crisis, the tone of the media cannot help but remain downbeat. As a result, more and more people are becoming disenchanted with the news and prioritizing reducing their time exposed to the media cycle.

Solutions Journalism emerges as a potential response to the grim news industry. Certified trainer in Solutions Journalism Juliette Gerbais talked to iMEdD during the International Journalism Forum 2023 about her practice, while she and her team from the European Journalism Center (EJC) enlightened journalists through the workshop “Introduction to Solutions Journalism” on how they can approach this contemporary style of storytelling.

Any topic can be a Solutions Journalism story. And there are many problems in the world. So, if there is a problem, it is very likely that a solution is out there.

Juliette Gerbais, Project Assistant, European Journalism Centre

Storytelling on TikTok: Opportunities for journalists

Three journalists explain at the iMEdD International Journalism Forum 2023 how they use TikTok to create impactful content that both informs and entertains the public.

What is Solutions Journalism?

Solutions Journalism is the practice of researching and presenting a solution to a widespread problem. It primarily involves an evidence-based investigation of responses from communities, organizations, or unorganized groups worldwide.

The solutions story, as presented by EJC, is built upon four pillars:

- Response: The stories one reports on and writes about are not focused on individuals or the organization but on the solution itself – how it works, and how it came to be.

- Insights: It is not a mere representation of the story but provides the material and information needed for others to recreate and respond to the problem in their own way.

- Evidence: There is an essential focus on data-based evidence, cross-checking, and quantitative results.

- Limitations: Presenting the response’s limitations and shortcomings and avoiding hype.

There has been a notable increase in media outlets adopting this alternative form of storytelling, and, in the last few years organizations dedicated to this practice have popped up, such as the Solutions Journalism Network and the EJC’s Solutions Journalism Accelerator program. At the same time, as reported by the Associated Press, CBS has provided training to its reporters in solutions reporting.

The impact has yet to be measured thoroughly, yet initial findings are promising. A 2017 paper hailed as as “the first true experiment on the effects of Solutions Journalism” revealed that exposure to solution information led readers to experience reduced negativity after reading a news story and fostered more favorable attitudes, both toward the news article and toward possible solutions to the problem presented in the story”.

Choosing the solutions path is a personal choice for journalists, and, as Juliette also observed, younger generations show a heightened interest compared to their older counterparts. “I feel like young people are more inclined to confront news fatigue and avoidance, seeking change”. And solutions journalism can benefit both young journalists and younger audiences. A study from the Reuters Institute on how young people consume the news states, “Young people are often put off by relentlessly negative news. They do not want the media to shy away from serious or difficult stories, but as part of the mix, they want stories that can inspire them about the possibility of change and provide a path to positive action”.

I have heard many journalists saying advocacy should not be a bad word for journalism. Is it bad to advocate for something you believe in?

Juliette Gerbais, Project Assistant, European Journalism Centre

Beyond “good news”, beyond “good journalism”

However, the question, “Isn’t that just good journalism after all?” which arose during Juliette’s workshop, remains. Her experience has taught her that misconceptions about the news practice she teaches are common in the journalistic community. Professionals in the field often worry about whether what they are writing is just another “good news” story –defined by a 1980s paper as “one for which the majority of the local paper’s readers would be satisfied or pleased that the event had happened or happened as it did. The tone of the story will be generally positive or upbeat”.

Juliette addressed these concerns by providing some questions that aspiring solutions journalists can pose to themselves:

- Is this story too good to be true?

- Even if the organization I am focusing on is trying to help, is this an actual solution for the community it addresses?

- Is there additional evidence that proves the solution is working?

- Is the data I am using good enough?

She argues that what sets the solutions piece apart from a “good news” story is evidence of its effectiveness. “And if it doesn’t work, you should report on it.” Data from multiple sources support the evidence. There have been instances in Juliette’s career where journalists started out with what they thought was a solution. “The more they read about (the solution), the more they understood that it didn’t work,” she points out. This introduces a new dimension to the story, explaining the limitations of the investigated response. The questions one should ask are:

- Why did the response not work?

- What did we learn from it?

- What can one do better?

When the advocacy case was mentioned during her workshop, Juliette followed the suggestion of “Introduction to Solutions Journalism” by the European Journalism Centre: It is better to avoid advocacy for a specific response. But during our talk, outside of the teaching environment, she offered a more nuanced perspective. “It is about asking yourself whether you, as a journalist, want to lean into advocacy or not. […] I have heard many journalists saying advocacy should not be a bad word for journalism. Is it bad to advocate for something you believe in?”.

Furthermore, evidence and journalistic neutrality come from perspective. This is accomplished when solutions offered by different organizations are compared and their efficiency has been checked. If only one organization contributes to the reporting and the data, the story falls short of being conclusive. “The point is to look a bit deeper”, says Juliette. This can also mean changing parts of the story, like who represents the human element. Telling the story of a single person and, most often, the founder, who is being presented as “the hero” who saves the day, can diminish the chance to highlight the collective efforts and see the aspects of the response more straightforwardly. “But usually, if you remove the good founder, there is really not much of a story to tell”. The point of the reporting lies in the solution itself and not the person executing it. That, says Juliette, can distinguish a human-interest story from a solutions piece.

Looking for the solution and setting the problem’s background

When starting, it is often hard for journalists to differentiate their previous reporting from the solution-oriented approach. Looking beyond the problem allows one to ask pertinent questions about each challenge: What can one do about it? Solutions Journalism is about finding the answers people gave to that specific question.

Searching for these people is an optimal way to begin – online searches, asking members from affected communities, or talking to experts can uncover responses not yet thoroughly reported. Solutions frequently emerge from proactive organizations, yet it’s essential to recognize that small regional communities and implemented policies can also significantly influence each problem. “If you have a full problem-oriented story and you introduce a solution only at the end, it doesn’t count as a solutions story because you are still mostly focused on the problem”. She continues: “A paragraph at the end (of the article) doesn’t give you time to talk about how the solution works or why it effectively addresses the mentioned problem[…] It is better to dive into it for it to be a good solutions story”.

Nonetheless, that does not make the problem any less important. Juliette has noticed that journalists sometimes start writing about a solution to an issue their readers are unfamiliar with, whether it’s climate change – a popular subject in the Solutions Journalism world– or other topics such as the rent crisis, women’s rights, or the marginalization of minority communities. Clarifying the problem is critical for understanding its response and familiarizing readers with the issue at stake. It can motivate them to search for the solution and take action in this direction, while giving them a sense of resolution and hope.

Summing up her extensive practice, Juliette concludes: “Any topic can be a Solutions Journalism story. And there are many problems in the world. So, if there is a problem, it is very likely that a solution is out there. The more we hear about a problem, the more people ask, ‘OK, what can we do to solve it?’ And, I think, in general, human beings want to solve problems”.