‘The Europeans fuss, but Niger has always been a transit country.’

This story was originally published by The New Humanitarian. It is republished by iMEdD with permission under a Creative Commons license and is translated to Greek. The New Humanitarian is not responsible for the accuracy of the translation. Read the original article.

6. Sahel: Geopolitical chess in the southern tip of the Sahara

The 10 crises of 2024 – Explained: 6. Sahel: Geopolitical chess in the southern tip of the Sahara

AGADEZ, Niger

Since deposing the elected government last July, Niger’s ruling military government has shaken up the country’s relationship with its one-time Western partners.

In rapid succession, the new government expelled French soldiers from the country, repealed a 2015 law that had been a cornerstone of EU efforts to curb migration, and then cancelled two EU missions working with Nigerien security forces on a number of issues, including fighting jihadist militants and stopping the movement of people from West Africa toward Europe.

Now, Niger’s ruling junta has revoked a military cooperation agreement with the United States, potentially forcing around 1,000 US troops to leave the country. The move further entrenches a pivot away from the West and towards Russia as a security cooperation partner that mirrors moves by post-coup governments in nearby Mali and Burkina Faso.

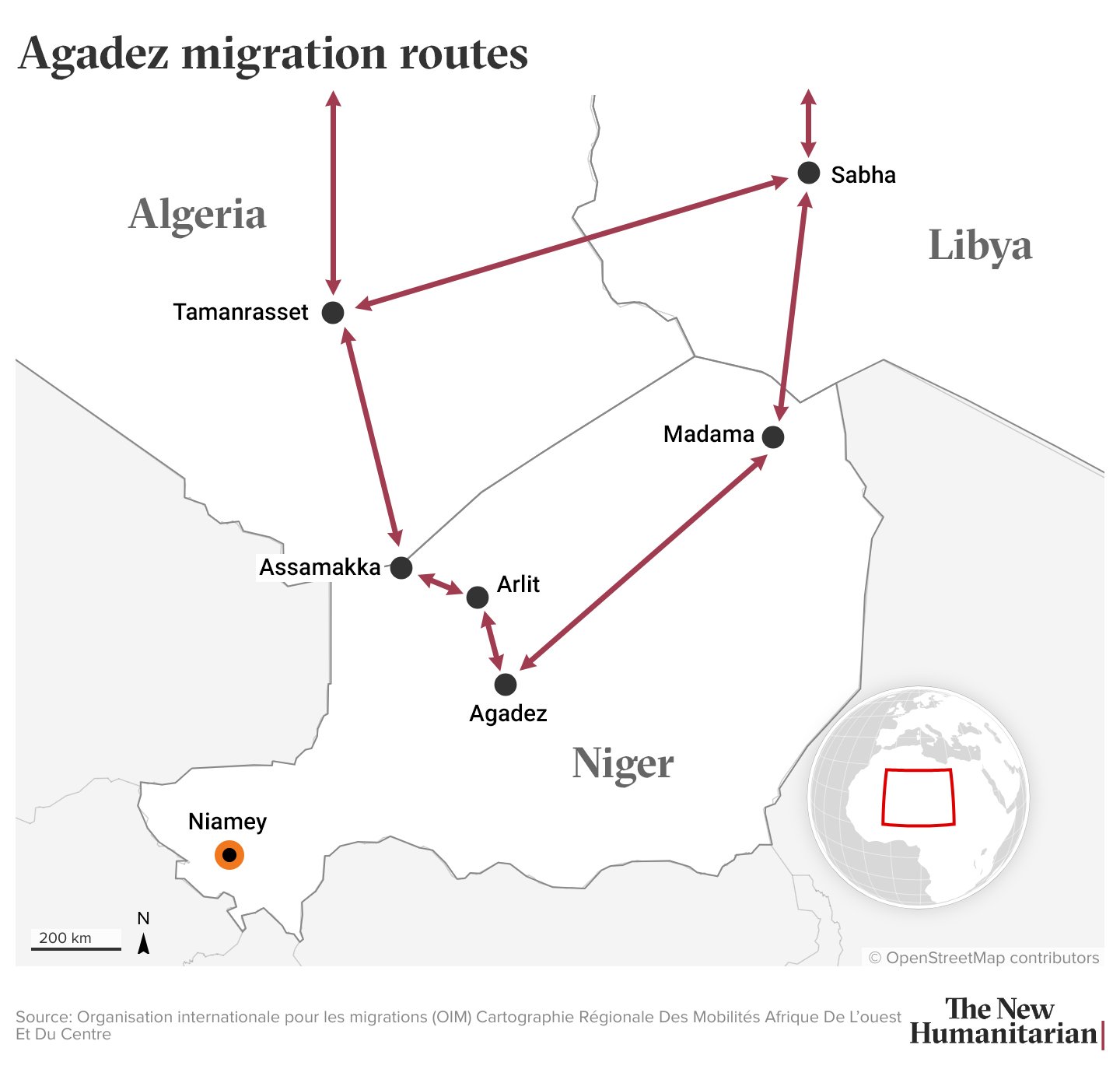

In the northern Nigerien city of Agadez – long a waypoint for asylum seekers and migrants hoping to reach North Africa and Europe – last November’s repeal of the 2015 migration law is having a tangible effect.

Shortly after it was enacted, the EU credited Niger’s migration law for reducing the number of people transiting through the country to North Africa. But migration via Agadez never entirely stopped; it was just pushed underground.

“The Europeans fuss, but Niger has always been a transit country. It is up to the destination countries to manage its flows, not us,” an adviser to Niger’s military leader Abdourahamane Tiani told The New Humanitarian. The adviser did not give permission for their name to be published.

During a visit by The New Humanitarian to Agadez shortly after the law was repealed, a driver at the city’s bus station said: “We are happy we can take the main road again. Before, it was forbidden. We had to go around.”

The bus station is now an official departure point for people wanting to cross the desert between Agadez and the Libyan border, around 900 kilometres away. Every Tuesday, authorities organise large convoys that are escorted by the army. People wanting to join line up in front of a police post to register their names as drivers call out, “Libya! Libya!”.

When The New Humanitarian was there, around 20 people were crowded into the back of three pick-up trucks, waiting to start the long, bumpy journey across the desert, which can take two to three days. The area around the bus station was abuzz with activity. Street vendors sold bags of water, dried dates, cigarettes – any provisions travellers might need while crossing the desert.

‘Everyone benefits here’

Once a destination for tourists, Agadez – which is a UNESCO World Heritage Site – fell on hard economic times following two rebellions by the the main ethnic group in the region, the Tuaregs, against the Nigerien government in the 1990s and 2000s. Those were followed by the emergence of Al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM) in the region, which put a further damper on Agadez’s tourist economy.

When migration across the Mediterranean to Europe via Libya started to increase considerably in 2013 and 2014, Agadez became a boom town for those from West Africa hoping to make the journey.

“After tourism collapsed, many residents turned to migration because it’s a very lucrative activity. Homeowners, transporters, merchants, restaurateurs, everyone benefits here,” said Boubacar Halilou, a former tour guide who switched to working in migration about 10 years ago.

Sophie Douce/TNH

Niger is part of the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS), a regional union that has a free movement agreement for members similar to the Schengen Zone. Anyone from the 15 member states could travel to Agadez without having to apply for a visa. From there, a whole industry sprung up – with people providing housing, food, supplies, and transportation – to bring people to the Libyan border.

The 2015 migration law made all of that illegal, causing deep economic frustrations among those who had made a living off helping to facilitate migration.

“For us, it’s not trafficking. We work like any travel agency. Migrants pay for their tickets; we have itineraries,” said Bachir Amma, the president of an association for people working in the migration business. “From one day to the next, we were told it was forbidden. Many lost their jobs.”

Under the law, people who helped smuggle asylum seekers and migrants to the Libyan border could face prison sentences ranging from two to 30 years and fines of up to 30 million CFA francs (around $49,000).

In 2018, the EU’s ambassador to Niger at the time, Raul Mateus Paula, told The New Humanitarian (then IRIN News) that the bloc had nothing to do with the law being enacted. “We learned [from] reading the papers that they decided to adopt this law,” Paula said.

Mohamed Bazoum, then Niger’s minister of interior, told a different story: “The Europeans requested us to reduce the number of migrants that were entering Libya. Without the law, we didn’t have any way to do that,” he said.

Bazoum was elected president in 2021, and was deposed in the military coup a little over two years later. Niger is now governed by a military-led National Council for the Safeguard of the Homeland, which Tiani sits at the head of.

‘We did not reduce migratory flows’

The migration law’s repeal by the ruling junta that deposed Bazoum and his government has led to relief in Agadez. “It’s a breath of fresh air for the city,” Halilou said.

Halilou works as a ‘coxer’, connecting people who want to cross the desert with transportation to Libya. Prices vary between 300,000 to 350,000 CFA francs (around $490 to $570). Halilou earns a 20,000 CFA franc ($32) commission for each seat he sells. “It’s picking up slowly. For now, I only have a few clients per week, but it takes time to rebuild contacts,” he said last December.

A report from the UN’s migration agency, IOM, recorded a combined 50% increase in movement across Niger’s northern borders with Algeria and Libya between December 2023 – when the anti-migration law was repealed – and January 2024, including a 94% increase in the number of people crossing to Libya. According to the IOM report, 75% of those making the journey were Nigeriens who were searching for work in North Africa.

While the repeal of the law sparked concern in Europe about increased migration, the overall effect remains to be seen. Last year, while the law was still in place, more than 270,000 people arrived irregularly in Europe by sea – the highest number since 2016.

Aside from 2015 – when over one million asylum seekers and migrants (mostly Syrian refugees) arrived by boat – a decade of EU efforts to work with countries like Niger to crackdown on migration hasn’t stopped people from attempting to reach the continent. Despite the apparent lack of results – and the high financial, human rights, and humanitarian costs – the EU is doubling down on the approach.

Niger is an example of how this approach by the EU has been a failure, according to Azizou Chehou, Niger coordinator of Alarm Phone Sahara, an activist network that provides assistance to asylum seekers and migrants who are in distress.

“We saw inexperienced drivers take solitary routes. In case of breakdown or flat tyre, it was guaranteed death.”

The movement of people from Agadez to Libya never stopped, Chehou explained. It only became more dangerous as it was driven underground by the 2015 law and smugglers took longer, more isolated routes through the desert to avoid the police and military.

“We saw inexperienced drivers take solitary routes. In case of breakdown or flat tyre, it was guaranteed death,” Chehou said, adding that Alarm Phone Sahara had found more than 300 dead bodies in the desert of people who had perished from thirst, fatigue, or after falling from pick-up trucks since 2016.

“We prevented passengers from following official routes, yes, but we did not reduce migratory flows,” Chehou continued, adding that the repeal of the law is actually an opportunity to better protect people migrating, by making the journeys more organised and regulated.

High costs, modest dreams

On the Tuesday The New Humanitarian visited Agadez, Toyota Hilux pick-up trucks paraded in and out of the labyrinth of ochre alleyways in the city, emerging with dozens of passengers in the back – no longer having to hide.

The passengers’ faces were covered by turbans and sunglasses, and their bodies were cloaked in long sleeves and even gloves – every surface of skin protected from the sand and scorching sun.

Not everybody taking this route is trying to reach Europe. Circular migration between North and West Africa long pre-dates the rise in migration across the Mediterranean over the past decade.

For those who do want to reach Europe, however, they will have to first navigate their way through Libya, where asylum seekers and migrants often end up in a prolonged cycle of detention, exploitation, and abuse that the EU has helped facilitate by supporting the Libyan Coast Guard to intercept people at sea.

For those in Agadez hoping to reach the EU, the allure of Europe – whether real or illusory – is strong.

In the courtyard of one of the mud brick houses where asylum seekers and migrants stay before they set out across the desert, Youssouf Sakho, a 28-year-old from Ivory Coast, was eagerly awaiting his opportunity to depart.

He had worked as a mason in his home country, and was now planning to try to go to either France or Italy. He’d already spent all of his savings – around 300,000 CFA francs ($490) on his stay in Agadez and the journey to Libya. To cross the Mediterranean, he will have to pay a smuggler in Libya another 700,000 or 800,000 CFA francs (around $1,100 to $1,300).

His modest dream for when he arrives in the EU: “I could work in tomato or potato farming to send some money to my family; there are no jobs in Ivory Coast,” Sakho said.

Edited by Eric Reidy.

The New Humanitarian puts quality, independent journalism at the service of the millions of people affected by humanitarian crises around the world. Find out more at www.thenewhumanitarian.org.