Award-winning Middle East writer and multimedia journalist Iason Athanasiadis explores Donald Trump’s Gaza vision through the lens of 21st-century trade wars and the global race to control the world’s most strategic chokepoints.

US President Donald Trump caused global shock-waves in February when he suggested that the US take over Gaza, remove its entire population, and redevelop the area into “something magnificent.” A few days later, he shared an AI-generated video on his social media, depicting a futuristic, luxury seaside development complete with bearded belly-dancers, a golden statue of himself, Palestinian children, and Elon Musk dancing under falling dollar bills. More than four months later, in the aftermath of the region-defining Israeli strike on Iran’s nuclear program, plans to transfer the Gaza Strip’s Palestinian population to Libya are ongoing, as part of a plan that critics say is an act of ethnic cleansing. So was Trump’s Gaza proposal a smokescreen for establishing a direct US presence on the world’s most sensitive geopolitical crossroad?

“It was a classic Trumpian negotiating tactic in that it opened with something outrageous that speeds things along by getting everyone scrambling to react,” said Michael Shurkin, a former CIA analyst now working for Senegal-based consultancy 14 North Strategies in an interview with iMEdD. “The bad news is that too many people in the Israeli government are taking it seriously and thinking to drive the Palestinians out.”

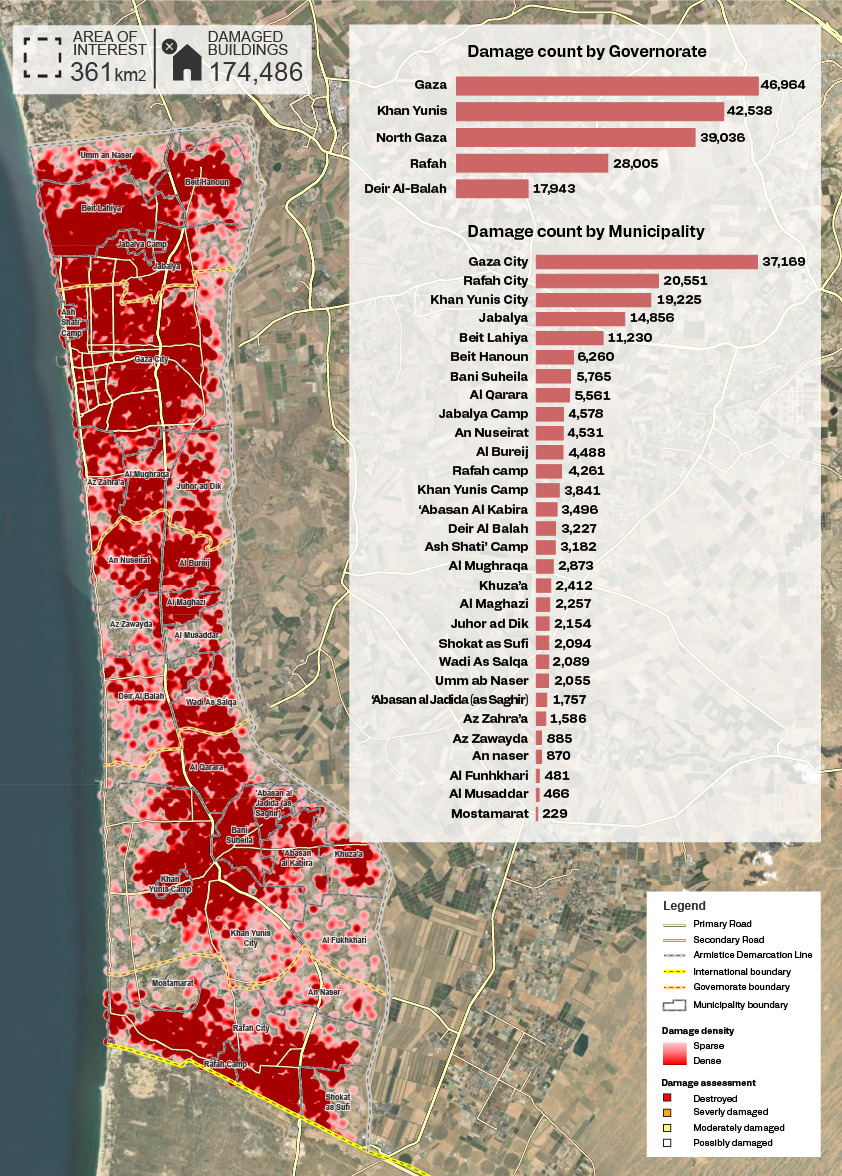

It was perhaps a real-estate developer’s idealized alternative to Gaza’s current appearance: a concrete wasteland, 90% of whose buildings have been wrecked by an Israeli campaign that pledged from the get-go to make the Strip unlivable. The US would “take over” and “own” Gaza without paying any money for it, Trump added.

“What does “we own Gaza” mean for Trump, if not the same as his “We are keeping the oil” during the Syrian civil war, or “We want Greenland and Panama?” asked Claude de Baissac, founder and CEO of Eunomix, a geopolitical and country risk advisor. “What you see here is a mixture of self-confidence, amateurism, hyper-masculinized on-the-fly decision making, ideology and a perception of superiority.”

Armories of the Middle East

The dark economy at the most crisis-ridden side of the planet.

“It’s a return to pre-modern politics.”

Developments in the intervening three months clarified Trump’s intentions. The US endorsed Israeli military operations contradicting international law in the Palestinian territories, Lebanon, Syria and Yemen, even while maintaining pressure on Egypt, Jordan and Libya to admit the Gazans. The Trump administration singled out China as its primary geopolitical competitor and escalated its trade war with Beijing. With the Red Sea emerging as the most likely theatre of commercial but potentially also military conflict between the two superpowers, proxy conflicts in shoreline states like Sudan and Yemen escalated. “Because the world war scenario is nothing other than a quick acceleration towards a nuclear exchange, we will never again have world wars like the 20th century’s,” said Hussein Askary, the vice-chairman of the Belt and Road Institute in Sweden, in an interview with iMEdD referring to direct conventional warfare between the armies of major powers. “If low-intensity proxy wars continue, then of course maritime straits like Hormuz, Malacca, Bab el-Mandeb and Suez will continue being extremely important.”

Geopolitically crucial for being the main maritime East-West connector, the Red Sea is the setting for several ongoing proxy conflicts in Ethiopia, Sudan and Yemen, whose influencers maintain interests in the Red Sea and are also linked to Gaza. Yemen’s Houthis have demonstrated that the Red Sea can easily be blocked on both entrances, whether in Bab el-Mandeb or on the Suez Canal. Unlike the Bosporus Straits, which the Montreux Convention bans warships from transiting in wartime, the 1888 Constantinople Convention permits passage through Suez. Any conflict involving global powers would therefore witness the Red Sea likely reprising the maritime war-theatre role it held in both the first and second world wars, when the Italian navy skirmished first with the Ottoman and then with the British navy. It is unsurprising therefore that both the US and China maintain a naval base in the Red Sea port of Djibouti, alongside France, Japan and Italy. In February, Russia too secured a port 1,000km further north in Sudan. In March, Somalia offered the US unlimited use of its Red Sea ports and airports.

“What Trump is doing is rethinking the geostrategic order,” said to the New York Times Donald Trump’s former chief strategist Steve Bannon in a reference to expansionist US pronouncements aimed at deterring perceived threats from China. “From the Panama Canal to Greenland, it’s just a naval strategy,” Bannon said to Kathimerini. “What he’s doing is securing the Panama Canal, so that the Chinese Navy and the Russian Navy cannot hook up and connect in the Caribbean.”

Whenever competition heats up between international trade corridors, so does the importance of geopolitical chokepoints. The spot where Asia and Africa meet across a waterway uniting civilization’s oldest sea to the primary East-West maritime superhighway is arguably the world’s most critical location. Just 170km from the Suez Canal, the Gaza Strip is the closest life-sustaining location. Its complicated ownership also opens it to disputation.

The Trump strategy of seeking to lock away strategic bodies of water like the Atlantic and Mediterranean that serve to protect the US-facing shores of the Eurasia supercontinent derives inspiration from 19th century geopolitical thinker Alfred Thayer Mahan. He argued that sea powers like Great Britain and the US could only remain dominant as long as Eurasian powers such as Germany, Russia and China remained disunited. He also advised the US government to build a canal in a part of central America that used to belong to Colombia, before Washington created Panama in 1903.

Trump’s assertion that the US will take over and control Gaza acquires new significance in light of current US activity around the Panama Canal and Greenland, and against a backdrop of deteriorating global security. So how does Gaza connect to the greater Red Sea region, and is Trump’s plan for the territory also part of a deeper preparation for an expanded global conflict whose demands, American war-planners calculate, could not be covered by existing US bases in Crete, Djibouti and the Persian Gulf?

“I hate to say it but Trump is better suited to this kind of wheeling and dealing,” said Shurkin, speaking during the US President’s May Gulf visit. “He can march into the Gulf prepared to make big things happen, some of it big – money deals, and also normalization with Israel.”

Location and water

Water streaming from the Negev Ηeights to the Mediterranean made Gaza in the late Neolithic period one of the earliest locations of human settlements. Fed by a tributary of the Besor Stream, the region swam into historical record as a Philistine town whose most famous resident was Samson’s Dalilah. Traders, armies and mystics made Gaza a thriving stepping-stone between the Nile Valley and the Levant.

Caravans from Egypt, the Fertile Crescent and the Nabatean kingdoms connected to the Mediterranean at Gaza’s ancient port of Anthedon, a Boeotian colony. By virtue of sitting on a thin sliver of land where two continents meet, the wider region became a geopolitical hub whose importance was evident through the various precursors to the Suez Canal connecting the Mediterranean to the Red Sea that two Pharaohs, a Persian Shah, Ptolemy and a Roman Emperor carved out of the Sinai’s rocky ground.

As the medieval world shifted towards modernity, Gaza remained at the centre of the dream to bypass the enormous geographical obstacle to East-West trade presented by Africa. The trading republic of Venice briefly considered the idea of reopening Pharaoh Necho II’s silted channel in the 16th century, as did Napoleon on his way to conquer Gaza in 1798. In the 1830s, an eccentric French socioreligious reformer called Barthélemy-Prosper Enfantin founded a techno-liberationist movement called the Saint Simonians, but official suspicion frustrated efforts to dig a canal.

Gaza after the opening of Suez

When the Suez Canal opened in 1869, Gaza’s importance skyrocketed. Britain purchased the bankrupted Egyptian state’s share in the project in 1875, and a group of influential members of the European Zionist settlement movement campaigned to convince London that only a Jewish Palestine on Suez’s eastern bank could truly protect the route to India.

Israel was created in 1948 out of a war that stripped away Gaza’s historically extroverted nature and compressed 40 percent of mandate-era Palestine’s refugees into an open-air prison. British Mandate-era Palestine ended up being reduced to a 40km strip which the Egyptian army retained at the end of Israel’s creation war, with Israel emerging with 77 percent of the territory and Jordan claiming the remaining 23 percent.

Decades of squalid living conditions ensued for a population that was to balloon to over two million by 7 October 2023. In the 1967 Arab-Israeli war, Israel went on to conquer the Jordanian-held West Bank and Egyptian-ruled Gaza. While the West Bank was intended to be returned in exchange for a two-state solution with the Palestinians, the accelerating settler movement in the 1970s, Palestinian factionalism and Israeli tactical delays resulted in a gridlock that contributed to the 1987 Intifada and creation of Hamas. By the mid-2010s, simultaneous terms in power for Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu and Donald Trump resulted in a joint annexation project. Ιn 2017, Trump recognized the 1980 Israeli annexation of Jerusalem, then offered a ‘deal of the century’ in 2020 that dangled $50bn of international investment before the Palestinians to build a parody of a state on a sliver of the West Bank and without sacrificing any Israeli settlements. They refused.

Houthi Weapons and the Two Deaths in the Gulf of Aden

What a private security executive in the Gulf of Aden reveals. The court documents on the Houthi weapons seizure operation in which two American commandos died.

Trade corridors and geopolitical footholds

But rather than generous gesture, Trump’s proposal may be a postcolonial ruse to carve out a foothold in a strategic piece of real estate with disputable ownership sitting at the world’s geopolitical core. Α Gaza perch would stamp Washington’s dominance on a critical spot where Africa meets Asia, and the Mediterranean segues into the Red Sea. At a time of deepening planetary crisis, it would offer Trump area-denial options against a China actively engaged in restoring Eurasian connectivity by resolving Middle East conflicts.

“In the current context, everyone’s competing with everybody; it’s so unstable,” said de Baissac, the security consultant. “What the Houthi crisis, the war in Ukraine, the civil war in Sudan and tensions in Ethiopia all tell us is that in today’s world you need to have alternatives and can’t rely on one set of dominant ports.”

“The US in the Red Sea isn’t so much about area denial as about not abandoning the place to others,” said Shurkin, the Africa analyst. “The Chinese have very good relations with the Ethiopians, Somalia, Djibouti, Kenya: they are present on the Red Sea and the western coast of the Indian Ocean.”

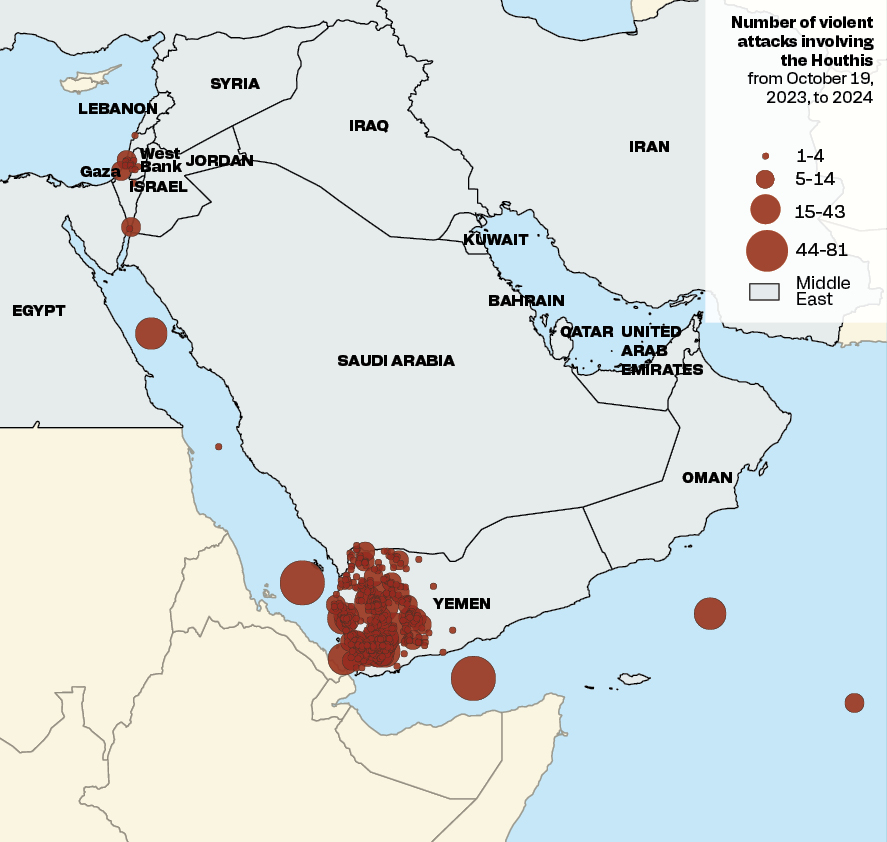

Trump’s priority remains managing US decline through focusing on China and the BRICS grouping’s challenging of the dollar’s global reserve currency role. Beijing has invested $1,2 trillion since 2013 in the ports, railways and highways that make up its Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) trade corridor, which in turn drives economies of scale in cost and delivery time for Chinese products. The disruption campaign led by the Yemeni Houthi militia since October 2023 has left Chinese ships largely untouched while targeting Israeli-linked ships, boosting the BRI further, a London-based insurance industry expert told iMEdD.

“It would take a sustained period of time without attacks on ships for confidence to be restored among shipowners,” said the insurance source.

Removing geopolitical obstacles such as Hamas, Syria and Iran are long-term and bipartisan US policies going back to former US President Barrack Obama and the first Trump presidency. They are seen as steps towards eliminating Iranian and, by extension, Russian and Chinese influence, and reinstating US hegemony. But despite Israel turning the Gaza Strip into rubble, and a series of operations that decapitated Iranian-supported organizations like Palestinian Hamas, Lebanese Hezbullah and Iraqi Popular Mobilization Forces, these actors remain stubbornly present, although reduced in potency.

“Trump is placing the following dilemma before Hamas and Arab states such as Egypt, Jordan and Qatar which can convince it: either Hamas leaves Gaza, or the Palestinians do,” said Sotiris Roussos, Professor of International Relations and Religion in the Middle East, University of the Peloponnese. “Secondly, it exerts pressure on Saudi Arabia to come to an agreement with Israel and get integrated into the Abraham Accords.”

The involvement of the Houthis in violent attacks

The size of each circle on the map represents the number of violent incidents attributed to the same geographical location by ACLED. Different incidents that occurred on the same day have been counted separately.

Data source: ACLED

Data processing & visualization: Chrysoula Marinou & Kelly Kiki/iMEdD

An Area that Changes Through the Barrel of a Gun

Dr. Marina Eleftheriadou, scientific advisor for the dossier “The Armories of the Middle East,” analyzes the region’s geopolitical significance, its complexities, and the ever-growing need for research and study.

Trains, trucks and supertankers

The war in Gaza impacted a wider geopolitical region, and drew in regional and global players. Iran-aligned militias shot missiles and drones at Israel and, in Yemen, the Houthi militia disrupted trade by denying the Red Sea to Israeli-affiliated ships. 15% of global trade and 30% of all container traffic passes through Suez but the percentage of overall trade traversing this region is increased by multiple other routes, including the trans-Central Asia Middle Corridor and the North-South Transport Corridor.

“War-risk premium has tripled and seafarers are asking for double or triple wages because they are risking their lives,” said John Faraclas, a London-based member of the shipping industry who runs the All About Shipping website. “So the Americans have to smash every terrorist resistance to ensure that Suez operates in order.”

In the absence of a western corridor comparable to the BRI, Trump’s 2020 peace offer to the Palestinians was motivated by the need to compete with the Chinese trade highway by normalizing the relationship between Israel and Saudi Arabia. This would clear a trans-Arabian Peninsula route for an overland trade corridor called the India-Middle East-Europe Economic Corridor (IMEΕC) that former US President Joe Biden announced in 2023, and which would bypass the Suez Canal. Several economists interviewed by iMEdD dismissed IMEΕC – which connects Mumbai to Europe via a yet-to-be-built rail-link traversing the Arabian Peninsula from the UAE port of Jebel Ali to the Indian-owned Israeli port of Haifa – as a political project and economic non-starter. While the route would potentially reduce transit time by 40 percent, it would also be limited to carrying just a fraction of the containers that ships can transport.

“I’m totally against IMEEC because it doesn’t serve the purpose of quick trade,” said Faraclas. “You would need hundreds of train-wagons to match the quantity of a single ship.”

While IMEEC is not intended to cross Gaza, the railway link entering Israel from Jordan is within rocket reach of Hamas, Iran or other militant groups, rendering it harder to insure and therefore less competitive. Without peace between Saudi Arabia and Israel, there is a big gap in the IMEEC where the Suez-circumventing railway segment would be constructed.

“Peace is a necessary condition for commercial transport,” said Viron Matarangas, an associate professor at Istanbul’s Bahçeşehir University and former Greek ambassador. “High war-risk insurance premiums are passed onto the consumers, which isn’t favourable for transporting goods.”

Data processing & visualisation: Evgenios Kalofolias / iMEdD

“Never a Good Time To Break Down” – Journalists in Gaza Continue To Report Amidst Fear for Their Lives

Four Gazan journalists reflect on how it feels to be reporting after nearly 20 months of war.

The Saudi-Israeli peace saga

Secret negotiations in the waning months of the first Trump administration culminated in Netanyahu meeting in Saudi Arabia with ruler Mohamed bin Salman and US Secretary of State Mike Pompeo. Knowing Trump’s presidency was coming to an end, bin Salman hesitated to sign a treaty that would mean ignoring the condition of previous Saudi rulers that a Palestinian state come into existence first. However, the further sidelining of the Palestinian issue over the next three years had convinced the Crown Prince to move to peace with Israel by the time Biden announced IMEEC in September 2023. The October 7 Hamas attack was timed to sabotage Saudi-Israeli normalization, and prompted Biden to complain, “They knew that I was about to sit down with the Saudis.”

“What the peace deal is really about is the US providing a security wrapper so they’re all financeable,” said Trump Mideast envoy Steve Witkoff, himself a real estate developer. “Today you can’t borrow money in those countries … because banks don’t want to underwrite war-risk because of Iran or the Houthis firing in a hypersonic missile and destroying a hypothetical data centre or other investment.”

Not only does Gaza form a land-bridge from Africa to Asia and from the Red Sea to the Mediterranean, but also an alternative to the Suez Canal. Plans to bypass Suez via Gaza have been around since 1855, when a British naval officer called William Allen first proposed it. The idea of building a canal named Ben Gurion (after Israel’s founder) occurred during a double blockade over land and Suez that Israel’s neighbours subjected it to in the 1950s and 60s. A conspiracy between Britain, France and Israel following the nationalization of the Suez Canal in 1956, whereby an Israeli attack would prompt the former colonial powers to intervene and retake the canal, was foiled by the US. In 1963, a declassified US report proposed using hundreds of underground nuclear explosions to construct a canal in Israel running parallel to Suez. Nothing came of that, but the idea recirculated in 2021 during a six-day blockage of the Suez Canal. With nuclear explosions no longer a viable construction technique, the project could only be built across the softer ground of the Gaza valley wetlands. But this remained a non-starter as long as Hamas were in play, as was an alternative idea to create a railway freight project called the Red-Med, whose terminus just north of Gaza made it uninsurable due to the risk of rocket fire. It became clear that Red Sea-Mediterranean interconnectivity could only happen once Gaza’s resistance was crushed.

Then, a real estate mogul-turned-US president came along who was the “greatest friend Israel ever had” and whose son-in-law runs a Saudi-backed financial fund.

With the international economy in violent renegotiation, Gaza’s upgraded significance is already visible in the geopolitical competition unfolding on the far side of the Negev Desert. Regional powers like Egypt, Turkey, Saudi Arabia and the UAE have been fanning civil wars and domestic instability in Sudan, Ethiopia, Yemen and Somalia.

But the Red Sea’s criticality is not just underscored by dysfunctionalities but also by heavy Chinese, western and Arab investment in its ports. Saudi Arabia kicked things off in 2017 when it purchased two Egyptian islands that had been used to blockade Israel in the past. By controlling Tiran and Sanafir, Saudi Arabia could offer Israel security guarantees in the event of a peace deal, or even a military base, as Egyptian officials worried. Immediately opposite these islands, Riyadh began constructing an $8 trillion business, luxury residential and tourism urban hub intended called NEOM that is intended to replicate Dubai’s role in the Persian Gulf. It is also currently building or upgrading a whole series of port facilities along its 1.800km Red Sea shoreline.

Other state-controlled actors have also heavily invested in the Red Sea. Dubai Ports World acquired container terminals in Djibouti, Jeddah and Egypt, while Chinese companies have invested in Egypt’s Port Said and Ain Sokhna ports, some of which were among those involved in a controversial $19 billion deal brokered in February between two global funds: New York-based Blackrock and Hong Kong-based Hutchison.

With BRI having a 12-year headstart on IMEEC, China is now shifting to transforming it from a simple trade route to an economic corridor by creating mixed docking, container and freeport business zones. This conversion will reduce delivery distances by performing car, electronics, and appliance assembly in situ, then loading them onto ships to be delivered to nearby markets.

“BRI is not just a trade route but a mixed production-and-transfer project the likes of which China first built in the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor,” said Mohammed Saleh Alftayeh, a UK-based researcher in political economy and defence. “Their economic model is building different types of factories, assembly and power plants along the route, and then shipping mined resources back to China and assembled products to the West.”

IMEEC will struggle to find entities to finance expensive infrastructure projects like a railway line, energy pipelines and fibreoptic cables spanning four geopolitically-risky countries. “When you search for who will finance IMEEC, its proponents say it will be the private sector, but they won’t find it attractive because it’s a money-loser,” said Askary, the economic analyst and West Asia coordinator for the International Schiller Institute. “IMEΕC is a political rather than an economic project.”

Regional escalation

While Trump and Indian Prime Minister Narendhra Modi pledged to revive IMEΕC in February, the region has destabilized more as multiple simmering conflicts reactivated. Israel attacked Iran, India and Pakistan dueled for a long weekend, ceasefires in Gaza and Lebanon were broken, the US bombed, then made peace with the Houthis, fighting resumed in Syria, and the Sudanese civil war reawakened as the government side took Khartoum. Peaceful competitive trade seems further than ever against a backdrop of large tariff impositions, begging the question of what role Gaza might play if the Trump administration decides to escalate further.

With pressure mounting on Washington to pull its troops from Iraq and US soldiers in Gulf Arab bases exposed to Iranian missiles, a semi-permanent military presence on Gaza could be seen by military planners as a solution. The slim, Mediterranean-facing coastline of Gaza sits on the spot where the African and Asian continental plates connect. It is just 170km from the Suez Canal and 200km from where the Gulf of Aqaba allows access to the Red Sea. In several ways, it forms the world’s junction.

Specialized Editing: Dr. Marina Eleftheriadou