During a one-on-one with Haïfa Mzalouat, Journalist and Editor-in-Chief of the independent, Tunis-based, media group, Inkyfada, iMEdD unravels the bloody business of migration in Tunisia, the EU’s role and the reality of being a migration journalist.

Immigration in the election discourse of political leaders

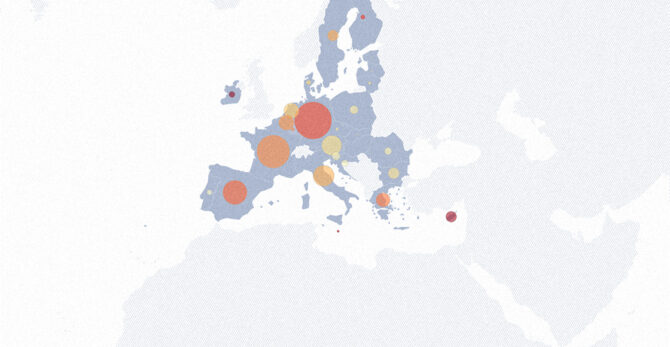

How did political leaders address the issue of migration and refugees, if they addressed it at all, during the extended election period prior to the tragic shipwreck off the coast of Pylos?

“Sometimes, when you are working on migration and you don’t feel the impact directly, investigative journalism is very important as a reference. If one day we are going to change the legal framework, media organizations will give the necessary material”, said Haïfa Mzalouat during the panel “Investigative Journalism, and migration: the costs of fighting impunity”, on the first day of the iMEdD International Journalism Forum.

As Inkyfada’s Editor-in-Chief, Mzalouat oversees all articles but also conducts her own investigations. Since Ιnkyfada was created in 2014, it has pledged to promote press freedom. By bringing developers, designers, and journalists together, Inkyfada produces dense pieces on Tunisian affairs, used by academic and non-academic audiences alike. In what is now an autocracy, after President Kais Saied’s suspension of the Constitution and announcement of rule by decree in 2021, migration is one of Tunisia’s many ongoing crises.

On July 3, 2023, the tension between locals and Sub-Saharan migrants in Tunisia’s coastal city of Sfax escalated with the death of a 42-year-old Tunisian man. This event added fuel to the fire of Tunisia’s racist migration policy, causing the assault and mass expulsion of migrants from their homes. As of September 2023, at least 2,000 migrants were forcibly expelled by Tunisian authorities and were left stranded in the deserts bordering Libya and Algeria with no food or water, with 27 migrants confirmed dead.

Unraveling the humanitarian crisis thread

“People often think that Tunisia is only a country of emigration. It’s also a country of immigration but the legal framework is not adapted” said Mzalouat. Indeed, many Sub-Saharan Africans migrate to Tunisia not to flee to Europe but to secure domestic job opportunities and better living conditions. However, Tunisia’s legal and social context poses an entry barrier to outsiders. Tunisia being a “safe country” for migrants is an illusion that the EU is desperately trying to uphold to curb migration flows to mainland Europe. In reality, flows to Europe are not reduced but rather made more irregular, with more migrants travelling without a VISA, along dangerous routes. In 2023 alone, 1,769 migrants died travelling from Tunisia to Italy, the world’s most lethal migration route.

In June 2023, the revision of the EU’s New Pact on Migration and Asylum made migration to Europe even riskier. The streamlining of asylum procedures in all EU countries meant that asylum applicants with a recognition rate below 20% will not be accepted in the host country. According to the European Union Agency for Asylum, while in 2022, Syrians had a recognition rate of 93% and Ukrainians 86%, Tunisians sat on the lower end of the spectrum with a mere 2%. The New Pact revision also endorsed deflecting responsibility to other countries and detention similar to Greek island models. But why is Tunisia so affected by this? And why now?

Europe welcomes Ukrainian refugees with an asylum system that averages more than 15 months of delay

The asylum reception system in Europe is receiving millions of Ukrainian refugees while having more that 700k applications pending.

The complex tapestry of migration politics

“When a subject is getting bigger, you sometimes have one kind of narrative, one kind of article. For me, everything is political, and we are often talking about migration only from a humanitarian perspective” stressed Mzalouat. The political context plays a major role in understanding the nuances of Tunisia’s migration crisis.

At the 2015 Valetta Summit, held to strengthen cooperation between the EU and Africa in addressing migration challenges, the EU Emergency Trust Fund for Africa was set up. While it succeeded in promoting conflict-resolution, the 4.9 billion euro Fund signified the first time that the EU directly linked development to migration management.

In the following years, a migration-development policymaking nexus became the norm. In 2021, the EU Neighborhood, Development and International Cooperation Instrument (NDICI) was adopted between the EU and Africa, with a 79.5-billion-euro budget . Although according to regulations, only 10% of the NDICI funds could be migration-related, the EU found ways to use migration management as a precondition to development assistance. In Tunisia and Libya, 3 out of the 8 development programs, equal to 1.6 billion euros, focused on border control and the return and reintegration of immigrants.

When a subject is getting bigger, you sometimes have one kind of narrative,one kind of article. For me, everything is political, and we are often talking about migration only from a humanitarian perspective.

Haïfa Mzalouat, Journalist and Editor-in-Chief of Inkyfada

On July 16, 2023, the EU and Tunisia signed a Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) to establish a mutual economic, trade and migration cooperation. Through a 105-million-euro financial support package, the deal aimed to increase border management, fight smugglers and strengthen the Tunisian coastguard. On September 22, the EU announced a first payment of 127 million euros to Tunisia; 67 million as part of the migration package and an additional 60 million budget support. “The EU is externalizing its borders to Tunisia for a very long time now. But the discourse and what they are actually doing is completely different. If you are trying to connect where the money came from and where it is going, it’s almost impossible” said Mzalouat.

Nevertheless, on October 3, President Saied rejected the funds claiming that they contradicted the MOU benchmarks and rather resembled a “charity”. Despite the unpredictability of these political maneuvers, one thing is certain; migrants will ultimately pay the price.

24 years, seven tragedies

24 years, seven tragedies: The survivors’ experiences and the collective trauma of an entire nation.

Navigating migration coverage

To tell migration stories, interacting with government officials, NGOs, and migrants themselves is necessary. Talking to the authorities can be complicated, but according to Mzalouat, “thanks to the work of advocacy that has been done before, some institutions can understand the notion of accountability” and are eager to share information.

Problems arise when one seeks the details. The International Centre for Migration Policy Development (ICMPD), an international organization that cooperates with EU member states and UN agencies has now undertaken the second phase of the ProGres Migration project, aiming to strengthen Tunisia’s migration governance. For Mzalouat, it’s interesting to ask organizations like the ICMPD about their political agenda. “They are always saying ‘We are not political; we are a technical organization’. But what does this neutrality mean?”, she said.

The same applies to humanitarian organizations. “If you’re going to Syria to help, you are going to wait for government authorization. And who is the government? The one responsible for all the turmoil” Mzalouat exclaimed. Humanitarian actors are relying heavily on activism to put pressure on governments because “they always have to be very ‘clean’. This shows the limit of neutrality”, she added.

Ιt’s often complicated to know how to report on migration without being “too out of place”. There are journalists with a lot of ego that will use their writing for glory, but it’s necessary to question one’s role and be respectful of other people’s stories.

When asked about a moment in her work that truly impacted her, Mzalouat said “I think it was the hospital. It was my worst field ever”, referring to her team’s hospital visit after the forced expulsion of migrants from Sfax. She described entering a room with a 6-year-old child with a broken leg and a man with a wounded head. With pictures being taken throughout the visit, Mzalouat kept asking herself “Should I publish these graphic pictures? People just got assaulted. They lost their house. They lost everything”. While it’s important to raise awareness, there’s always the ethical question; journalists’ duty lies in protecting people from traumatizing situations and allowing them to construct their own narratives, not white-saviorist ones.

According to Mzalouat, it’s often complicated to know how to report on migration without being “too out of place”. She admitted that there are journalists with a lot of ego that will use their writing for glory, but it is necessary to question one’s role. “We can of course be proud of what we are doing, but it’s important to be humble” she concluded.

Watch the full panel discussion here: